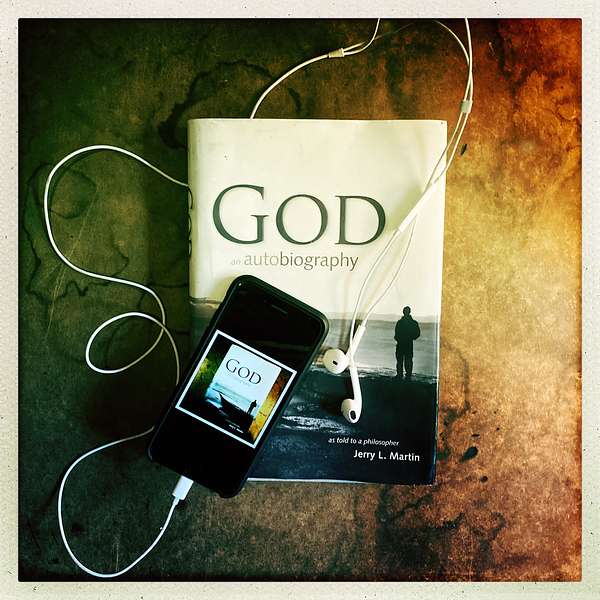

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

195. The Life Wisdom Project | Aesthetics and Philosophy in Chinese Spirituality | Special Guest: Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum

In this episode of The Life Wisdom Project, philosopher Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum joins Jerry to explore the fascinating world of Chinese spirituality and its connections to Western philosophy. Jonathan shares his transformative journey to Mount Jiuhua, one of China's sacred mountains, offering insights into how nature and spirituality are deeply intertwined in Chinese thought.

The discussion bridges Eastern and Western philosophies, including Heidegger's idea of Gelassenheit (letting go) and Buber's concepts of I/It vs. I/Thou relationships. These ideas are unpacked to reveal how they shape our understanding of desire, values, and the importance of suspending desire.

Listeners will also enjoy a powerful Zen parable about a master and a thief, which uncovers profound spiritual truths. The conversation extends to the Taoist principle of Wu Wei, or effortless action, highlighting the significance of aligning with the natural world.

Jonathan and Jerry further discuss the Ethics of Care and virtue ethics, connecting these ideas to Confucian ethics, where context and flexibility are valued over rigid rules. This episode offers practical insights into applying these philosophical concepts in everyday life.

Relevant Episodes:

- [Dramatic Adaptation] God Shares His Earliest Interactions In Chinese Spirituality

Other Series:

- From God To Jerry To You- A series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

- READ: "These Have Been My Most Faithful Servants"

- THE LIFE WISDOM PROJECT PLAYLIST

Hashtags: #lifewisdomproject #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Share your story or experience with God! We'd love to hear from you! 🎙️

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 195 Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon.

Scott Langdon 01:11: This week we bring you a brand new episode from our Life Wisdom Project series I think you're really going to enjoy. I know I really enjoyed spending time with it while putting it together. One of our favorite guests on the podcast, professor Jonathan Weidenbaum, returns to talk with Jerry about 20. God Shares His Earliest Interactions In Chinese Spirituality

Scott Langdon 01:28: Because of Jonathan's expertise in Eastern religious studies in particular, we knew from the start he would bring just the right touch of insight and knowledge, mixed with the perfect amount of wisdom and understanding, to the conversation. I'm thrilled to report to you that we were right. And then some. Oh and, by the way, if you like what you hear on God: An Autobiography, The Podcast and would like to support our work, the best thing you could do is share a link to our podcast with your family and friends. It's completely free for you and completely priceless for us. We are so grateful for each and every one of you who listen and we're honored that you spend this time with us. Here now is Jerry and his special guest, dr Jonathan Weidenbaum. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:18: Well, I'm very pleased to have Jonathan Weidenbaum, who's done a Life Wisdom before, with us, maybe actually one of the first we ever did. But here is a topic that I thought of him particularly. I thought of you, Jonathan, because of this, Jonathan teaches, philosophy and world religions and so forth in New York City, but often has been a traveler to Asia, and when he comes back from Asia he has many wonderful photographs. So this is someone who has an aesthetic eye.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:52: And one of the first things I'm told in this episode- God to Jerry- is you haven't picked up on the Chinese aestheticizing of nature and which God then explains, reflects a sense of the expressive side of nature which is, of course, is my the divine expressiveness through nature. So let me just read a slightly longer passage. Shortly after that, you know, what's special about the Chinese culture, and we talked about the Chinese, we're not to have a genetic theory about the Chinese. We're talking about Chinese culture, the sages and poets and so forth. There are other people fighting and stuff, but these were the sages and poets and such, are an unusual people and this is in this episode, “They resonate to Nature.”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 03:46: Capital N in my text version, “Feel its tones and rhythms, are attuned to hear it, listen attentively to it, and it tells them certain things. They catch its vibrations and try to match their vibrations to it.” Well, God's statement goes on, but one question is does that make sense to you in terms of you know, like you're encounter with things in that part of the world? But also, then the next question would be how do we benefit from this? You know, okay, what can I do? Okay, it's wonderful, they're resonating to the divine metronome. At one point is the analogy- the divine hum of the universe. But what are we going to do with that?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 04:40: Among my favorite travel experiences and among the most rigorous of my travel experiences was a climb up Mount Jiuhua in China, one of the sacred mountains. The whole mountain is devoted to Dizang, one of the Bodhisattvas, or Buddhist savior beings in Buddhism, who descended into the underworld to rescue all the I don't know if I want to use the word soul in a Buddhist context but all the entities that were caught there to help release them. And this is a temple, you know. I mean the natural vista is beyond the imagination to describe rolling mist over the mountainside, full of nunneries and bells and temples and incense, and you know pilgrims and others hiking their way up and among other things. And the reverence for nature and the way in which nature is appreciated as a kind of the abode of the spiritual, if you will, is almost unequaled in regards to anything I've ever experienced elsewhere. I mean it really was an utterly profound experience.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 05:50: Yeah, you see these in a lot of the Chinese art. You know the paintings. It's really quite extraordinary the way they bring nature out in a kind of again to pick up a word used that God uses in this passage it's a reverential attitude of nature. Wow, you know, there's something sacred here.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 06:14: Yes, yes, yes, and you know, of course you had me look at some quotes from this incredibly rich chapter, and rich it was, and I came up with three, but I found a fourth and I want to begin with this one.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 06:35: Okay.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 06:37: It continues nicely, Jerry, with what you're talking about. You're sitting and contemplating privately. It's like halfway through the chapter. “At this point I was told just to sit with God for a moment. I was led into my inner self. Looking at nature from that vantage point, I saw it aesthetically. Samuel Taylor Coolidge said that fiction requires the quote willing suspension of disbelief unquote. The aesthetic attitude requires the willing suspension of desire that allows the order and beauty of nature to reveal itself uncoerced,” and immediately, you think I know that you've done a lot of work on Martin Heidegger and Heidegger's relevance for philosophy, and what strikes me is his notion of Gelassenheit, which from the German translates you can correct me if I'm wrong a kind of peaceful yielding.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 07:33: A kind of release, if you will, a peace through release, that this is a kind of suspension of our coercive and arrogant manipulative tone toward the natural world in order to allow it to disclose itself to us. So we're not of course, now switching to Heidegger's kind of philosophy, so we're not preoccupied with beings, like a small bee for our manipulation and use, but we allow being itself to come into the room. I am still reminded of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, whose works on Taoism I have never fully immersed myself in. You know Buber had made some critical remarks about the Buddha, but he had a profound appreciation for Taoism. I think very early on, before he wrote I and Thou, he translated a work on Taoism, something to do with the aphorisms of Chuang Tzu, but so I can't speak so much for Buber's sort of take on Taoism.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 08:36: But certainly I think of Buber's I/It and I/Thou relations, relationships of utility and of use which are important, we have to survive, are the I/It mode of being. But the I/Thou mode of being is a kind of presentness to what's before us in such a way that we take it in in its wholeness, that we don't violate it, and we allow ourselves to be overtaken, well not necessarily overtaken and Buber rejected a kind of the I melting into the Thou, still a kind of putting ourselves at risk to open ourselves up to the other, truly, without pitching hope into our own categories. And I was struck by the relevance of those two continental philosophers, Heidegger and Buber, when I read this really lovely passage of yours.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 09:27: Yeah, that's fascinating. So what should one do? Well, it implies you don't always- I have mixed feelings. Well, I'll tell you what the mixed feelings are. There are two truths here. There's a truth to desire. Desire is what is the engine of our lives? You know that's, you might say our goals, and that setting of goals is one of the sources of our values, our ideals. At the same time, that I appreciate that that's certainly a big part of the cultural history, you can explore that in various ways, there's another side that isn't, and that's this willing suspension of desire, where you encounter things and just sort of let them be. Buber talks about speaking thou to nature, but I'm not even sure you have to speak thou. You know, encounter, take it in, and you might say, sit quietly with it.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 10:39: I'm struck by the Zen parable. As you know, half of Zen Buddhism is Chan, excuse me, I apologize. Chan is the Chinese ancestor of Japanese Zen and half of Chan Buddhism is Taoism. You know, Mahayana Buddhism went to China to absorb Taoism. But this parable, or this little narrative, I love it.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 11:00: The master's in his cabin on the side of a mountain. A thief crawls in in the middle of the night to steal something. The master sees the thief. The thief is frozen in his tracks. The thief is terrified. He begins to slink out of the cabin and the master's like, wait, don't go empty-handed. He gives the thief his clothes. Now he's totally naked and he's sitting outside looking at the full moon in the sky and he says poor man, I wish I could give him this beautiful moon and this parable, this narrative, whatever you want to get so many levels and layers to it, representing these two different modes of being. You know, the thief can steal and steal, but he's still stuck in this one mode of existence. You know, the master has like nothing, but yet looking at the full moon, somehow representing the totality of things yielding itself.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 11:55: I don't know I don't want to mutilate it with explanation, you know, somehow I don't want to violate it, you know.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 12:06: You draw from it something that's always hard to articulate. You know that's not what it's good for. You might say it's good for taking in and you might say having your soul and psyche informed, formed and informed by it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 12:47: Contrasting it to some other ideas of nature as having an order we should conform to that sounds like rules or something, a rational scheme. God says it's more like joining an instrumental group and fitting in with the harmonies and the patterns.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 13:07: For the Chinese, very intuitive a sensibility, and I'm not musical, but I watch with amazement when I do see a group of people with musical ability sitting around and the way they will just sort of play and then someone will start something and then another will pick up, maybe on a different you know violin rather than a guitar or whatever and play off it. You know, just kind of join in and then maybe they will take it off in a different direction and the others will join into that. And you know the vision of God in God: An Autobiography is rather unusual, but part of it is, among other things, God is omnipresent and so you know you're flowing with the divine or cosmic harmony. You know whatever language is meaningful to you. Again, it's hard to articulate these things, but a lot of it is a training.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 14:09: If you ask, what are we to do? Well, it's to keep our minds, hearts, souls open and to be able to be present to what is presenting itself to us and not always have to think, oh, what is it good for? What am I going to do with it? Not even what's my duty? Maybe you don't have a duty, maybe it's a moment with significance. That's all that you need to do is simply respond to it within a kind of wholehearted way.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 14:44: I love when I teach the section on Chinese religions to my class wu wei, the notion of wu wei, this idea of course translates as non-action, but doesn't literally mean non-action. It means living in harmony with nature, accomplishing more rather than less by moving in harmony with things, not forcing ourselves on things. And I always I tell a story from my life, so, when I was a teenager, I was in a wrestling team and I was all full of muscles, you know, Jerry, and I had a lot to prove. So my dad, said to me with his thick Brooklynese, “John, let's go outside, I'll teach you how to cut wood, with a saw, you know.”

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 15:33: I'll stop imitating him. But then I said oh, no problem, please. So we went in the backyard. He takes a piece of wood, puts it on the trunk of a tree and says here's the saw, cut it. And of course I'm like you know, I have to impress him. I have to show how tough I am. I have to show the world how tough I am. So I put the saw in the wood and I go to cut it and the teeth just get caught in the wood and no matter how hard I push, in fact the harder I push, the more the teeth are stuck in the wood. It's not going anywhere. And I say my God, lumberjacks have to be the most muscular people on the planet. So my dad says John, move aside. I move aside.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 16:18: He takes a saw out of the wood. He just moves the piece of wood around. So now he's going with the grain of the wood. Okay, I was going against the grain of the wood. So he takes a saw and he says let the saw and the wood do the work. Use the whole teeth of the saw, just move it back and forward. Let the saw do the work. He cuts it in half, in two and a half seconds, you know.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 16:43: So I was utterly humiliated, but I think of you know, the idea, of course, not to beat this one to death, but the idea of sort of accomplishing more by moving in harmony with things you know and not forcing yourself on them. And the more you force yourself on them, the more recalcitrant the world becomes, you know.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:02: Yeah, so you, you go with your environment and it becomes not the object you're acting on. So, as a kind of partner you know that you're with– with which you're in concert, something like that.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 17:20: I never thought of my dad as a Taoist sage, but you know, I think that there was a lesson that was imparted. I think you've expressed it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:26: Oh, yes, and he knew it. You were young. He had been around and he knew a lot of life experiences. You've got to figure out which way does the grain go. Or even something in other sections here, Confucius talks about doing what's fitting, which is also a kind of aesthetic concept. What's fitting?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 17:55: I love the stress on context over rule. And that takes me to another quote from the reading for today God says, “Proper behavior cannot be achieved by conforming to a general rule. One may pay careful attention to the situation and adjust behavior in the most fitting way,” and then it goes on and explains for in the Confucian version of the golden mean, to get to go too far is as bad as not to go far enough.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 18:32: And you know it's interesting, Jerry, because I've spent a career teaching courses on ethics, and inevitably you teach the ethical theories that revolve around a formula, you know utilitarianism, the greatest amount of happiness, Kantian ethics, the categorical imperative, social contract theory, natural law theory, we can go on. They all, a lot of them, have some principle, some abstract formula. Now I don't want to give a depressing note to our talk, but when my beloved was on her last days in palliative care, you know they, the head of palliative care wanted me to have the life support shut off and he explained it's really, the right thing to do for Kasia, my wife, and of course I agreed with them a hundred percent. The only problem is that her parents were not ready for it yet, not just quite.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 19:35: So, I felt torn between two duties: the duty to my beloved and what she would have wanted. I think palliative care was correct, that's what she probably would have wanted. And but at the same time I had a duty to Kasia's parents too.And Kasia loved her parents above all. It was not something I could simply dismiss. So the head of palliative care he knew that I, because he had an informal conversation with me a day or so earlier, he knew I was a teacher in ethics. He knew I was a philosopher. People in palliative care, they take courses in ethics. What did he do? He recited the Categorical Imperative, and this is kind of the second formulation Treat everyone as possessing intrinsic worth, not as a means to an end, but as ends in themselves.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 20:22: That's somehow listening to time. Yeah, of course, of course. So, in the groundwork to a metaphysis of morals, Immanuel Kant gives us a number of formulas of what's called the categorical imperative. It's what you must do, regardless of consequence, regardless of context. And you know, of course, the one well-known one is that act according to that rule that you can will to become a universal law, that you would have everyone do the same thing if they were in the same situation. And if the answer is that you can't have them do the same thing in the same situation, then you should not do it yourself. You're making yourself an exception. But the second well-known form there's a number of formulations that categorically compare it. The second one here, Jerry, I apologize, I'm getting all abstract here but the second one is treat each and every human being never as a means to an end, but always as ends in themselves, as of intrinsic worth, not as subjective for use by others. And by the way, if Kant scholars are listening to this, I apologize if I'm getting a tiny bit off, but you know I have to abbreviate a little bit. So, and the problem was, it's not obvious to me how such an abstract formula can really give me concrete guidance, because I was torn between two duties and I don't want to sit and unpack how the theory seems to founder against the concrete situation. But in my ethics classes over the years, probably the most entertaining part of the classes is when I give students different scenarios, a trolley problem, different sort of thought experiments, to show them how the formulas behind the main ethical theories can sometimes come up against the problem. Or that runs against our intuition, or it leads to a consequence we may not love. However, on reflection and in conversing with others about my situation in the ICU over those very difficult days, I recall a different kind of ethical theory. This is called ethics of care. Now it arises among a feminist theory, it's in the background of a feminist movement within ethics. Yet at the same time there are elements of the ethics of care that always resonated to me, with thinkers like Martin Buber, who I mentioned a little bit earlier.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 23:01: Not an abstract formula, not an abstract principle, but the cultivating of nurturing caring relationships with a human being in front of us and in the writing of some ethicists of care I think of one figure, Nell Noddings, in particular, it seems to have almost a rich phenomenology, a richly descriptive approach to our experience, that it stresses context and in this regard there's also some parallels with the ethics of care and virtue ethics. There's a stress on attentiveness to context, on relationship and how that takes more priority than beginning with an abstract formula. You know, and on reflection I think if I had to examine one or a type of ethical theory that offers the most guidance, the most wisdom for such concrete, difficult situations.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 24:07: It would be an ethical theory that begins again, not with an abstract principle, not with a formula, but with a certain experiential attentiveness to the nuances of context and the concern for everyone involved. And in this case in ethics of care, I would say it's not a massive surprise that sometimes ethicists of care also appreciate virtue ethics and it's not uncommon in virtue ethics sections of a class, some people would teach Confucius as an example the cultivation of Ren, of Li, of propriety, of politeness, of gentleness. So there is wisdom in those kinds of ethical approaches.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 25:01: Yeah, and it's very situational. In the passages referred to in this episode, Confucius talks about when speaking to your superior, speak this way. Speaking to your colleague, speak this way, when speaking to a subordinate, and of course you could go on. When a father speaking to a daughter, speak this way, daughter to a father, speak this way, and you know, a neighbor to another, fellow citizen to another, and so on and so on, and each one he's putting them mainly there in terms of, well, what's the relationship? Because that's an awful lot of our relevant context in these things. But there's no implication that that's the only thing.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 25:46: You look at the entire context, what is going on and what are the dynamics of the context. You know, where does it seem to be going? You were sensitive in the case of the kind of exit from life procedure. The parents, her parents are not ready, and so that's a very fine sensitivity, but we have to be sensitive to one another, not just respect for one another or treating each other according to duty, but sensitive.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 26:22: Yes, my big problem with palliative care in this situation is they wanted me to take this principle and to override instantly, roughly override the needs of the parents, and I had to be, I felt that I had, I was a son in law, I had to be mindful of this nexus of relations that I'm a part of. So I guess it's not just a question of context and not beginning with an abstract principle, but also being attentive to relations, and I think that is one way I can even move it even a bit closer to Confucian-type insights.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 27:00: Yes, yes, and it's not just that situational aspect changes with time. You can say, well, I'm talking to my wife, but on what occasion am I talking to my wife? I'm talking to my wife a certain way. You know what just happened in her day. Is this going to bring up a difficulty? Well, maybe not. She just had some setback in some respect and so on. You know these and they're very nuanced and it's even hard to take. You know one can't theoretically take in the entire context. You know that'd be overwhelming. But somehow you have to develop those intuitions, instincts, whatever you want to call them, the sensibility that rather responds to what's crucial in a situation, what's going on in the person.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 27:52: And that's a beautiful place where Confucian philosophy and virtue ethics really meet. It's a cultivated human being of certain qualities that we want to see in human beings.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 28:06: Yeah, the question, it seems, for Confucian ethics is I don't know how these translations work but how to be a gentleman, how to be a superior person. You're trying to figure out how to become the kind of person you should become. That's the fullest version of yourself. That's very similar to Aristotle's ethics and similar to a lot of humanistic ethics. It's almost a form of be all you can be, but it doesn't mean all you can be, be the right stuff that you can be, and so that you're loving, kind, gentle, also dutiful, also defending them with your fist if that's necessary.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 28:53: I almost see Confucian ethics as almost kind of in between virtue ethics and care ethics, because it is about cultivating but it's also being attentive to relationship.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 29:06: Well, thank you, Jonathan. It's wonderful to have you participating in the Life Wisdom Series and always very, very good to see you.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 29:15: Jerry, always my pleasure, always my pleasure, give Abigail my regard. Thank you so much.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 29:21: We'll do so. We'll do so.

Scott Langdon 29:33: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Jerry Martin. I'll see you next time.