The Wake Up Call for Lawyers

The Wake Up Call for Lawyers

Meditation That Unlocks Wisdom

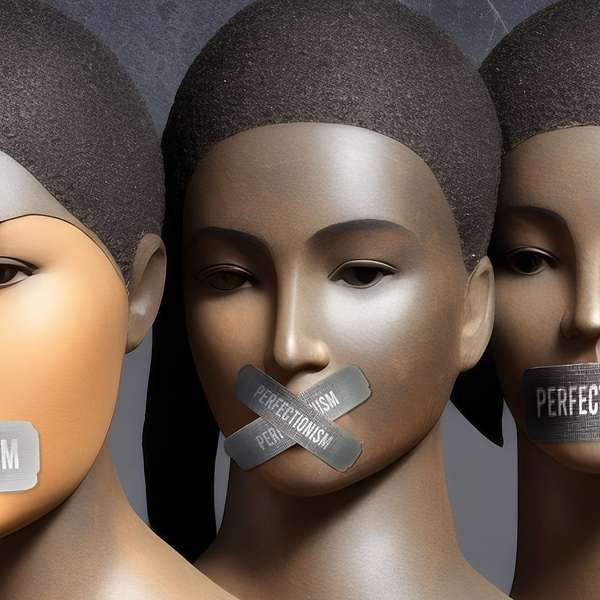

There’s a way that my habits and patterns block whatever wisdom I have. I think I know where to point, but my fear that the direction isn’t perfect, stops me. I think I know what to say, but perfectionism whispers, “what if that’s not it?”

Every so often during meditation, my habits fall away and I can see perfectionism through a loving lens, as just a constellation of thoughts, forming and dissolving. When that happens, wisdom is right there, waiting. Sometimes it waits like a signpost. Sometimes it shows up like gravity, reminding me to anchor to the earth. Sometimes it’s like peaches in summer, round and ripe and ready for picking, if only I remember to lift my gaze and gently open my hands.

(For everyone struggling with what freedom means right now.)

Hi everyone, it’s Judi Cohen and this is Wake Up Call 439.

In her final few paragraphs of Chapter 17 of The Places That Scare You, Pema Chodron talks about the last two perfections of mind, meditation and wisdom. She essentially says, meditation makes wisdom available.

She refrains the “the threefold purity” practice which I mentioned on the last Wake Up Call: “No big deal about the doer, no big deal about the action, no big deal about the result…” in slightly different language. When we sit down to meditate,” Pema says, the practice is to “leave behind the idea of the perfect meditator, the ideal meditation, and preconceived results[, and] train in simply being present. We open ourselves completely to the pain and the pleasure of our life.” And then, “because we see our thoughts and emotions with compassion, we stop struggling against ourselves. In this way, the wisdom we were blocking…becomes available.”

For me, it’s not easy to sit down to meditate and leave behind the idea of the perfect meditator. There is so much perfectionism inside this heart/mind, so, striving to “achieve” that, is alive and well.

For fifty years, or sixty if I go back to kindergarten, I took in the message – from my parents, from society – that I need to be perfect. Took in, and believed.

Becoming a lawyer strongly reinforced that belief because perfectionism is one of our highest values. Throughout law school I believed I had to understand everything perfectly. I had to read every case, grok its meaning, articulate the parties’ positions and motivations and arguments and why each was reasonable or not, clearly understand the ruling and dissent, and be able to articulate the meaning of the case in the larger context of whatever course it was assigned.

At the same time I knew that I didn’t understand perfectly. That there were things I didn’t get, or couldn’t articulate. Perfectionism paired perfectly with knowing I was imperfect.

In law school in my day, professors called on us by our last names, we were expected to stand, state the case, and then remain standing to be grilled or humiliated in front of the class. Plenty of times we’d be kept standing the entire class, depending on how well we were able to spar with the teacher, or permitted to sit only when some other student jumped in or the teacher moved on in disgust. There I sat, day after day for three years, knowing I didn’t have perfect understanding, believing I was supposed to, and living in terror of having to reveal my imperfection.

For me, and maybe you can relate, perfectionism in the classroom context activated anxiety, worry, and depression. It kept me up at night. It got me up at 5am. It was the shaky ground on which I stood (or fell over) and the common ground for my classmates. It accompanied me into practice and was the common ground for me and my colleagues because it’s so highly valued in our profession. Everything we do has to be right, from citations to punctuation to diction to winning, and there’s literally zero room for error. They may occasionally be room for loss, but never for error. Sharon Salzberg, the great meditation teacher, came to the Mindfulness in Law Teacher Training last Sunday and at one point, commented on how hard it must be when we do our best but end up turning in a brief six days late. I think we all smiled and didn’t at the same time, because we all knew – and all of us here know, every lawyer knows – it’s never six days late. It’s more like the pain of turning in a brief six seconds late.

I ended up porting perfectionism into my life outside the law, too, naturally. Especially in those early days without a strong mindfulness practice, perfectionism snuck into my parenting, my housekeeping, my relationships – none of which ever was or ever will be perfect. When my daughter was little she was a prolific artist – she’s still quite good – and her work was glorious and messy and imperfect. It was one of the great joys of motherhood, to hope that maybe I hadn’t transmitted perfectionism to the next generation. (I’m not sure she’s say I didn’t, now, though.)

And then naturally, perfectionism translated onto the cushion. Even though I’ve known from the first time I sat down that I’m no perfect meditator, I had an ongoing sense that I should be. This belief, or formation in my mind and heart, that perfectionism is the ideal, got in the way of simply paying attention, which is all we are pointing at when we sit down. For years I believed we sat down in order to feel better. Then for another set of years, I believed we sat down in order to be better.

What I’ve finally realized is that we sit down in order to allow love to emerge. Which is not different from allowing wisdom to emerge. Pema says it more simply. She says that instead of all that, “train in simply being present…. Open completely to the pain and the pleasure of our life.” Meaning, let go of striving to be the perfect meditator or to experience the ideal meditation or to achieve anything at all, and just notice the body breathing. And when the attention wanders – when we, or our meditation, become imperfect, which for me, happens a hundred times in a sit – be glad about noticing the wandering, imperfect mind. Sit with the pain of wanting to do it right, and the love that reminds us that isn’t possible because meditation, like life, and like love, is imperfect.

Once we see that, maybe we can also see that pretty much everyone has some perfectionism, some striving to feel better or be better. And once we see that, and realize we’re not alone, compassion can arise, compassion in the form of love: love that remembers that everyone lives in terror of being called on in one way or another. And once we see that, we can follow Pema’s instructions and “stop struggling against ourselves.”

In my experience, when we can stop struggling for perfection, or against imperfection, then wisdom can emerge, the moment when, according to Pema, “the blockages created by our habits and prejudices start falling apart…and the wisdom we were blocking…becomes available.” The wisdom of knowing that imperfection – maybe not in terms of a filing deadline, but certainly in terms of being human – is, by design, perfect.

By the way, three years of law school, I was never once called on. I spent every night reading and every moment in class afraid my imperfection would be revealed, and it never was – or at least in that way. All that terror and I never got to see that I could just be smart enough. Of course that might not have been what I saw, back then. But it could have been a start.