Start a ripple ...

Start a ripple ...

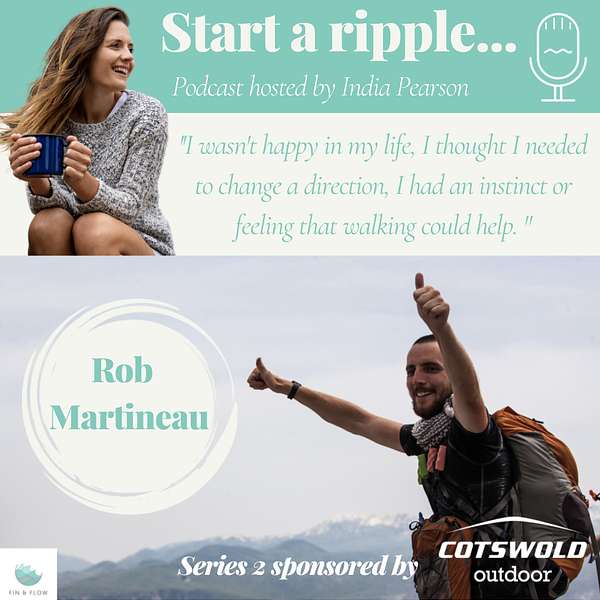

Rob Martineau | From wondering to walking the West Coast of Africa

Rob Martineau is the writer of Waypoints, an account his 1,000 mile walk in West Africa, which explores why we’re drawn to wander, and the ways a long walk can reset a life. Outside of writing, Rob is founder of TRIBE, a nutrition company, and TRIBE Freedom Foundation, a charity that fights human trafficking. In this episode we explore the good and bad side of solo adventure, the power of walking as a healer, and how kindness can be found in strangers.

Find Rob on Instagram - @rob_martineau

Tribe’s website- https://wearetribe.co/

Tribe Freedom Foundation - https://tribefreedomfoundation.com/

Rob's book ‘ Waypoints’ - https://www.amazon.co.uk/Waypoints-Rob-Martineau/dp/1787331369

This series is proudly sponsored by Cotswold Outdoor, the outdoor experts working to change the fabric of outdoor retailing. Find out more about their sustainability mission and services on their website.

If you have any questions or would like to suggest a guest please get in touch! You can email India via indiapearsonclarke@gmail.com or send a message via Instagram @india_outdoors / @finandflow / www.indiapearson.co.uk

~Music - Caleb Howard Almond ~

You can find this episode on iTunes, Spotify and many other podcast platform

If you have any questions or would like to suggest a guest please get in touch! You can email India via indiapearsonclarke@gmail.com or send a message via Instagram @india_outdoors / @finandflow / www.indiapearson.co.uk

~Music - Caleb Howard Almond / @oakandalmondcarpentry

India Pearson 0:03

Hello, I'm India and welcome to the second series of starter rebel podcast. This series is proudly sponsored by Cotswold outdoor, the outdoor experts working to change the fabric of outdoor retailing. You can find out more about their sustainability mission and services on their website. Now, this podcast is a platform for me to chat with inspiring folk that are making ripples in their lives by moving in nature. And I'm here to find out a little bit more about how this connection with movement and nature is having an impact on their mind, body and the environment to my hope the conversations that come from this podcast will encourage you to get outside, move, dream big, and see what happens from the ripples you create. Alright, it's time to introduce my guest. Robert Martin new is the writer of waypoints, an account of his 1000 mile walk in West Africa, which explores why we're drawn to wander and the ways a long walk can reset a life. Outside of writing, Rob is the founder of tribe, and nutrition company, and tribe Freedom Foundation, a charity that fights human trafficking. In this episode, we explore the good and bad side of solo adventure, the power of walking as a healer, and how kindness can be found in strangers. Hello, Rob, and welcome. Start a Ripper podcast. Thanks so much for having me, India, great to be here. Ah, it's awesome. Awesome getting you on the podcast, you're the last guest in the second series. So get super, super excited to have you here. And so could you just start by telling telling listeners a little bit about your background kind of way where you've got to live where you've been. So it's an idea of kind of looking back at the ripples that you've made in your life up until now give a bit of context.

Rob Martineau 2:15

So I suppose two main things that I do, firstly, a writer. So I'm the author of a book called weak points, which hopefully we'll talk more about, which describes a walk in West Africa and explores how a long walk can be a healing and transformative experience. And then alongside that, I am co founder of a company called tribe. And we make natural sports nutrition products. So amazing energy and protein bars, and also have a charity. It's just a charity called the trade Freedom Foundation, which exists to combat human trafficking. So those are the two main guys that blocks of my life in terms of work. And I suppose, really excited to be having this conversation with you is, certainly through my life, I suppose some of the key like junctions, where I've made changes in my life have come about through long journeys and journeys, where I've taken myself out of my old life, my old life was working as a lawyer at a law firm and going into nature, spending time on my feet and living in a very different way. And those a couple of points in my life have been the I suppose, the gateways for me into what I do now. And so definitely really resonated with me the themes of your podcast and your experiences. So really excited to have this conversation.

India Pearson 3:37

Yes, maybe so. So okay, let's go back then you you worked for a law firm. And, and then you decided, I can't do this anymore. I need to change up my life. What sort of what happened between, I guess those years where you went, I need to change what I'm doing. So then suddenly, walking across Africa.

Rob Martineau 4:03

I think I sort of fallen into law. I was really privileged, obviously to had an education University and to have the opportunity to go to law school. And I was funded through law school by a law firm, and I started work at that firm, and I quite quickly became, I suppose disillusioned with the lifestyle, I began to feel to me that it wasn't doing me good. I was working often 80 or 100 hour weeks, I was eating three meals a day in the office county and I was spending probably like 22 out of 24 hours inside each day. And I began to feel that things just I suppose physically and in my head as well that I wasn't living my best way I suppose producing my you know, some an environment in an environment that was best for me, basically, and I began to feel that I needed to change, change something and I'd always been interested in the idea of like a walking pilgrimage, not so much in like, directly religious sense. But the idea that you could go on a long journey on foot and through that, discover something about yourself and change the sense change yourself. I read lots of books which explore those kinds of ideas back through stuff like Walden through and more modern journeys as well. I suppose I had all of these ideas bubbling around. And I began, I suppose planning a journey. And the idea really did is described and waypoints just began, as could I go on a long walk, and it changed my life through it. And I was at that stage just had the idea for the walk, I didn't have an idea of particularly anywhere I wanted to go. But I'd always through writers, I love being drawn to that region of West Africa, where I travelled to, which is the countries of Ghana, Togo, and Benin, on the Atlantic coast in West Africa. It's amazing part of the world. And I began looking at maps, reading more about it. And I came to quite a natural juncture at the law firm, to leave and I handed in my notice, and bought a flight to Accra and it in which the capital of Ghana and spent six months working there, and it was an amazing, we're talking about a really amazing journey. And it definitely opened my eyes to so many things. And it completely sort of changed the course of my life.

India Pearson 6:25

Yeah, and I know that, whilst you decided to make this big change, you also kind of created some new rules in your life, Is this right? And you started to limit the number of possessions you had. And so why was this and what what did it do for you to do such a thing?

Rob Martineau 6:45

Okay, part of the idea of the walk for me was that it would almost be a bit like a farce that I was struggling in the lifestyle I was needing, I felt I had so many inputs coming at me from so many different places, and that they were all kind of checking information or stimulation of me in ways that I didn't really want. But I didn't really know how to kind of, not just keep doing that keep replies emails, keep kind of going out for drinks, keep doing all the stuff that I didn't necessarily, I didn't really stop to query, why I was doing it or what it was doing to me, I was just kind of doing it all. And the idea for the wall quite consciously it was to try to pull myself out of that, and live in a very different way. And one of the elements in some of the Explorer waypoints, particularly in the kind of desert section was restricting the amount of possessions I had will be just for a short period of time, it's a bit gimmicky in some ways, but the idea was that I wouldn't have more than 40 possessions and partly is practical. Because walking, I was carrying everything on my back. You know, I have my tents and so on. So if you have too much it weighs you down. And travelling late is an advantage. But also think in terms of my headspace and something that I was really drawn to the idea of a living in that minimal way, and having a really pared back routine. One of the things about walking in that way is it really, you only have one kind of goal each day, it's a really simple way of life, you get out you have your miles to complete that day, you get to where you're going to set your tent, you set your tent, I'd rent my clothes, set them to dry, make some food, I'd sleep and then I'd come and do it again. And actually that rhythm of life coupled with you know, not having much that you could distract yourself with I didn't have an iPhone, I didn't have a TV didn't have any of the things that are normally chucking so much information out at wine, or at least in the lifestyle, I was living taking myself out of that I found a really, like really beneficial. And I think I took a lot from it.

India Pearson 8:49

You still limit the amount of possessions you have in your day to day life now.

Rob Martineau 8:57

I definitely was a kind of for a period of time, I definitely tried to keep I suppose take some lessons sounds a bit arrogant, I mean lesson to take some of the things I learned from the walk and apply them in my day to day life.

India Pearson 9:13

I think it's that idea that the more you have, the more you want. Right. And and you can easily get into the trap, both for possessions and with, I guess sort of life's journey of doing things because you should have them rather than because you need them. You know, and I once listened to a podcast about minimalism, and it was sort of saying, you know, you buy a house, and you've got your house and then suddenly, you have a hallway and because you have a hallway, you need a rug around and because you have a rug runner, you need a Hoover and it was sort of going through all the things you have one thing and then because you've got that you need something else to look after that thing and it just accumulates and you look around the space that you've got, and you just go wow, how that This has happened without me realising. But it can be a really detoxing feeling, I think content just letting go of physical possessions and and yeah, maybe realising that actually, you know, you managed to get by with just 40 items without whether items that you ended up losing along the way because you thought actually I don't need this anymore.

Rob Martineau 10:21

Yeah, I definitely charted stuff as I went and sort of like lighten the load and is definitely walking and I do a lot of long distance running. And I suppose like, light mountaineering and definitely just like, keeping things as light as possible has such a benefit. It was, but I really, yeah, well, you're saying that millet minimalism really resonates I love one of the books I talk about a lot in waypoints is Walden by by Thoreau, and he was written like 200 or 250 years ago. And it's pretty funny reading him talking about furniture as if furniture is the most unnecessary thing. And he's kind of talking about all the people in the 18th 19th century kind of becoming accustomed to furniture as if it's something that we shouldn't need at all. It's quite funny even now, it seems absurd not to have furniture, but so kind of a tune. So I suppose our comfort levels and what we deem, like comfortable has become so kind of cushioned in a way.

India Pearson 11:26

Yeah, it's funny because we've got to pay a sort of address bit of random connection. But in our garden, we've got an area where so where I think they're sweet peas or something grows like that. And it's quite wild. We've never planted it. But my dog loves sitting in it, like her bed, like she creates this dog bed around it. And we, we now leave that area to be grow wild because she just loves it and it makes you think, you know, she doesn't need a cosy fluffy dog bed that I think she needs. So you know, because she's quite happy to sit in the bushes. And his that's her favourite place ever. And I guess maybe think of that when you're talking about furniture is this sort of bizarre concept? I guess is that is that why do you think walking appeal to you because walking, you don't need any equipment. You know, there are plenty of sports out there. For example, I love paddleboarding. I need a paddleboard to paddle I need I need the paddle itself, you need the fin all those sorts of things. Whereas with walking, I guess technically you need a pair to trainers. But do you even need that, you know, their fee is this one of the reasons why doing doing an adventure like this on foot was was so appealing.

Rob Martineau 12:45

Definitely a walking Zoo really. And it's been really interesting during through lockdown seeing how this bigger thing walking has become for lots of people is in a sense, the only activity people could often do that walking for me. I think that the way that it's so simple, and that you can access lots more places on foot, in a sense, you're not restricted by where the road is, or that was definitely a really appealing element to it. And I think one of the main things was what it allows in terms of, I guess, connection with places and with other people you move, moving really slowly, to typically moving at like three miles an hour, you can't really speed up much beyond that. And you essentially are quite vulnerable, you're just on your own with your pack. And I found that that allowed me to travel in a way that I think would have been harder for any other, I suppose means that seemed very natural to arrive in a place that might be far from a guest house or a store and for people to kind of take take you in and to the food and a safe place to sleep and to spend the night there and just create some fleeting connections and then to move on the next day. And actually moving that way, day by day was a really amazing way to travel. And I think some of the connections, I was able to kind of build with people because I was on foot. And actually if I had arrived, you know motorbike or four by four or whatever it is. One you wouldn't need to have stayed in the places I stayed because the distances you would never really stop. Stop there. And also that there would have been a barrier that there wasn't in quite the same way when I arrived on foot. So I think from that perspective, it was a really, it's a really amazing way to travel to travel on foot.

India Pearson 14:36

And it's interesting, you talk about that the connections that you made being so special. But were you ever because obviously you did this by yourself. Were you ever lonely? Or did it just did it just that idea of kind of walking by yourself or just your pack and a meeting or people along the way Give you the opposite feeling was there ever times when you thought I'm so I'm just by myself, give me friends.

Rob Martineau 15:10

Definitely there were periods like that, especially in parts of northern Ghana, which is much longer distances between the settlements and they'd spend nights, long days on my own maybe two or three nights in a row camping on my own. Definitely, that can be hard. And it's way partly because you don't have many distractions. And so you're just alone with your feet, your steps and your mind. And that is kind of challenging, but also, they miss people and miss those interactions. But I suppose the majority of the journey, I was often at walking alongside people. So if you're walking down, we'll be walking village to village and I'd walk with them for an hour, and then they peel off and I walked by myself for a bit and then someone else would join on the track when we walked together. And so often I was with people. And often people were curious to what I was doing. So you'd have, like natural conversation and say, I didn't too much, I had a lot of negating some of the ideas that try and explore and waypoints the difference between solitude and loneliness, I think solitude can be a really important thing and something that I was consciously seeking out in some ways, and I thought it'd be good for me. And walking often is, when people go on long walking journeys, or short ones, you know, going away for the weekend walking, often they are looking for that. That experience of solitude, which perhaps allows connections with other things, whether it's the landscape or you know, nature and things that can can help help our minds or help our bodies and say, certainly, oh is suppose aware of some of those ideas or ideas beforehand, and was probably consciously in some way trying to kind of reach out, reach out for that sort of treatment suppose,

India Pearson 17:01

because I guess actually equally, you could feel lonely. Being in a crowd of people, you can feel lonely, being in a relationship, you know, and I think that's interesting. And a really great point that you make, about the difference between feeling lonely and in solitude. And solitude is actually can be quite an empowering feeling. And embracing that. Were there ever times. Obviously being by yourself and you're saying you are uncertain, you are vulnerable? Where you felt like you're in danger because I think what puts people off wanting to do something like this? I know what sort of always was worried me, although I've travelled solo a few times before and I've loved it and I've never come back. It's been the best thing I've ever done. But the the thoughts go through my mind beforehand. What if this happens what if this happens and by myself? What were there any times when you felt you were in too deep? What have I done? And did you have Were you nervous before you went with these sort of pre existing ideas? Definitely, I

Rob Martineau 18:13

I was over the weekend I was running in the Pennine so I did kind of three days running the longer Pennine Way and last night I just camped out in a bivy bag on the side of one side up in Yeah, up from the pigs and I definitely felt I was kind of out of the habit of just sleeping in would essentially like field by myself and some runners came past like 1am in their training something with their head torches, definitely when you suddenly hear the footsteps and I was pretty remote place. And you definitely feel that like sense of nervousness, I think when I was in West Africa, I got used used to that lifestyle so quickly, in a way I was kind of camping every night and I I got really into it and actually I didn't really feel nervous. Then I think after I'd got over I think that perhaps before I left I had some nerves but quite quickly after I'd sort of got into the rhythm of the journey I became quite comfortable with the lifestyle and I was in a part of the world where I was made to feel always like there was almost a kind of protective shield around me in some ways the only time I ever got into any trouble which was normally just unnecessarily things like heat exhaustion or a couple of times I say collapse as dramatically you know and you just let your body kind of give gives up and that happened twice and immediately I was gonna pick out there were so many people kind of trying to work out if I was okay like giving near the I needed water and helping me back to my feet and every time I was welcomed into, you know, settlement or village or someone's home, they would then be telling me like what to watch out for on the road or If it's a sort of look in, in the next village, and it was definitely I felt that I was in a part of the world or in, in an environment where, which just wasn't dangerous. And in those countries and I think one thing, when when you go, is it, maybe European guy, there's so many privileges you have. And there's obviously a legacy of history that coming from Britain. But I think one of the things is true, and it's sad, but walking anywhere in the world is probably safer as a man than as a woman. And that's completely unfair. And it shouldn't be the way but it probably is the case that, you know, sleeping out in the tent on your own and anywhere is maybe it shouldn't be, but is, you probably feel safer as a guy.

India Pearson 20:56

Yeah, I think that, I think that is one of those things, isn't it? And if I was, if I ever see is kind of a woman, I don't know, hitchhiking by herself or something. I was like, oh, gosh, what are you doing, but if I see a man doing it doesn't ever crossed my mind, you know. So? Yeah, it's just one of those things that society has created for us. But it's lovely hearing you talk about the villages that you came across and the people that you met. And I think it's really, it's a good thing to remember that the human race, obviously, we hear so many awful things on the news, but the human race is kind, you know, there is so much kindness within the world. And you've obviously experienced that. But you must have experienced real culture shock as well. finding yourself walking into these tiny villages, do you have any sort of fun stories that you share with us from from the back about times, when you've just bought in these villages, and they've embraced you with ceremonies or spiritual awakenings, or anything like that,

Rob Martineau 22:02

there is quite quite a lot, I suppose offset one of those and set the scene a bit maybe in some of the parts of Garner and a banana in particular I was walking through there's definitely like, a very palpable sense of there being like a community of people that that the sharing perhaps much more, or at least more visibly than perhaps where I come from in London. So I'm, I live in a street in shepherds, Bush, you know, I get all my neighbours, but I'm not sort of I don't know, everyone, and I'm slightly detached from, from most of the people I live around, which I think is sad in lots of ways. Whereas in the parts of West Africa is in particularly in the countryside, that wasn't really the case, often, the communities would be very tight knit, and there was I would get invited the whole time, often, if I was walking in to be a wedding, people would rush out and pull me into the into the wedding, we should be outdoors and dancing. And it was surreal for you to come for I'd been walking for kind of five hours, you like a bit like whacked and not quite sure what's going on. And then suddenly, in a wedding for half an hour, and then on my way. And there was I was also very lucky to get not asked to participate, but to sort of to visit some of the ceremonies. And there's an amazing ecosystem of traditional religions in that part of West Africa in particular. And Benin is where the Buddha religion comes from, for example, in southern Ghana is walking through an area where the Ashanti culture is dominant, and they have these amazing ceremonies and festivals where they celebrate their cultures and often, their ancestors. And that often revolves or sometimes involves kind of trance ceremonies and amazing music and certainly things that I wasn't used to saying, Where I'm from in London, and it was, again, really special to be able to at least take part as a kind of watcher in those in those ceremonies and feel that you're, you're kind of part of part of them. And visually, they can be really amazing, like masquerades and I mean it really incredible to see. So there's a lot, lots of lots of that. And I think again, I'm tired of the reason was being offered you kind of stuff happens to you maybe in a way that it doesn't. Yeah, you can fast and you just kind of fall into what's happening around you. And it's great

India Pearson 24:41

to have to go with the flow with it, don't you really a lot of the time. Now, I know that in the book, that you you reflect on, on grief. And I'm interested to hear from you how you feel that the simple act of walking Nature, within Africa sort of helps you come to terms with the grief that you were dealing with. Because I guess, from my experience, I've, you know, moving in nature can be so powerful, which is why I've started this podcast just to chat with people about the powers it can have for the mind and the body in so many different ways. And I know that for you, coping with grief was one of those. So yeah, if you could sort of elaborate a little bit more on that and tell us how it how it helped.

Rob Martineau 25:33

Absolutely. I think there's, I suppose, two things to say, hey, actually, the first thing, which isn't exactly answering your question, but I kind of set out on the walk with maybe quite a simple idea in my mind, that I didn't set out to kind of write a book. And actually, I only started writing the book about four years after I got home. When someone very sadly, someone I'm very close to had a breakdown. And that person was in psychiatric hospital and I was visiting them every other day for the kind of month long period that they were in hospital when I began thinking again about this most my walk and wouldn't have done for me seeing how walking gait apart and that person's recovery. In the last couple of weeks, he was in hospital, a volunteer would come and take him for a walk each day just for an hour. And then after he left hospital, walking became a kind of important part of his routine. And I definitely made me think in a different way about how powerful something as simple as walking can be any sort of bring it back to myself, I guess I, I, my dad died when I was very small. And I'd never really wasn't consciously something I felt was, say a problem in my life, you know what I mean? I didn't feel like I was kind of dealing with grief in any way or didn't feel like it was something that I had unresolved in any way. But walking through one of the things is, again, so powerful about walking is it just opens it can open up space. And I thought I needed to walk to kind of get a new routine and to shake off what I was becoming in that office. But actually, perhaps more what I needed was to confront things that I just hadn't even realised I needed to actually that kind of space that that routine, and that rhythm of life opens up I think can be a really amazing thing in that respects. You just have so much time to think and you have so little distraction. And I think also that effort, that connection, reconnecting your body and mind in certain respects. Because before I was always hunched up, hunched over a desk and reusing my body and actually spending too long, it's in my head, but not thinking I don't not really engaging important parts of my mind. And walking, especially over a very long period of time seems to kind of unlock things for me. And gradually, rhythm I just began kind of thinking more and more about my father about what he meant to me about. He was big into mountaineering and I suppose some of things that I've gone on to really inspire my life and and say as in the book, I tried to explore that journey from a personal perspective, but also look a bit more, I suppose some of the mysticism of the psychology of walk, walking journeys, and how they can be used as healing or ways to confront things that are that are unresolved.

India Pearson 28:53

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, the amount of times that if you've had a busy day at work or whatever, and he's come home, he's got just need to go for a walk. You know, how many people do that so many of us do. We just need some headspace. But to do that for a prolonged period of time, I can imagine we haven't got the distractions of social engagements or the news on your phone bleeping at you. It creates new space in your in your mind to reflect that I guess in in ways where they have always in the past been, I guess, coveted by everything else that's been going on. And yeah, we can easily shy away from stuff I think distract ourselves with everything else that's going on in our in our lives. But the simple act of walking is so powerful and you explore that in waypoints beautifully and said to you before we started recording, how I found reading parts of it really meditative myself because you kind of go into the rhythm with you and actually At the end of the book you write, there's no end or summit just steps on a circuit that could go on forever. I thought that was really beautiful. And could you tell us a little bit more about this reflection and why you wrote it.

Rob Martineau 30:17

That stage I think that it comes from the kind of mountain section of the book. And as I say, the books loosely structured around three kind of regions, the kind of rain forest region, desert region and the mountain region. And each of them explores different ideas connected with those landscapes, and maybe the psychology of those landscapes. That I think reflecting on is a very famous pilgrimage to Mount Kailash, in the Himalayas and stead of going to the summit of the mountain. The people who made that pilgrimage, they do suck, second parameterizations of it. So walking around and around. And the idea in those pilgrimages, and some of the Buddhist ideas around pilgrimage is that the point isn't to kind of reach an end, that the value in the pilgrimage isn't about getting to a point B or reaching the church or whatever it is reaching that mountaintop, it's, it's what's going on in the steps and in the middle. And actually, that is a really powerful kind of metaphor for anything. Often it's, it's the journey, it's the effort of the journey, it's the struggle of the journey, and then it's that that generates the transformation and generates the positive energy generates momentum. And I think I was trying to, I suppose, reflect on that, in terms of what I was taking from the journey and taking is that kind of near near the end, but actually, it was much more about the doing rather than the arriving. And

India Pearson 31:57

yeah, no, definitely, I think, definitely, I think you can easily set yourself tasks, you know, I need to run the marathon, for example, or whatever it is. And yeah, the end when you in reflection, the end point is never what the way you learned your lessons from it's, it's, it's the middle parts of doing it. So how many miles Did you did you actually walk? that journey is about 1000 miles. And you did it in how long?

Rob Martineau 32:26

Did it take a long time? So it was I spent six months out there, but I was spending kind of often I wait a place for two, three weeks, there might be something that was like ceremony. Yeah. So I was often walk for very, I'd walked in very long days, you know, 3040 mile days sometimes, but then I'd have long periods where I was in a place of spending a long time in a monastery. And so they've gone through the journey itself was was, was always walking as it were, in terms of how I travelled, I was spending long periods along it, kind of

India Pearson 32:59

Yeah, yeah. And then going back to the UK, if you didn't return to your to your job, you know, to your trade, and you've gone on to do something quite different. Was there was the job that you do now? And she co founded tribe? It has, do you think the walk influenced what you wanted to do within your life moving forward?

Rob Martineau 33:28

Death, as far as the two aren't necessarily like completely connected. But definitely it gave me a different perspective. And I think it gave me I was so lucky to have the opportunity to do that. That trip, the Walker, I was, I was 26 maybe and I'd had enough savings from working at law firm, I didn't have any ties that meant that I couldn't do it. And I recognised a privileged position that that is, you know, 99% of people wouldn't have the chance to do it. So I was really lucky to do it, but it definitely gave me I suppose a confidence perhaps in taking the the less certain step and sometimes that can bring like amazing benefits, but it can unlock things and I suppose that is something that I tried to carry through into other like big decisions in my life and in terms of junction junction points I try and always recognise, not recognise but remember that often the best times so that when I've done the best thing it has been my it's been the hard thing or the thing that initially doesn't look like the sensible thing to do. And I think starting tribe tribe actually grew, I should say, out of another journey, I set out with two friends and we did 1000 mile run some years ago, across Eastern Europe and run it's got a long story short, but it turned into this kind of Forrest Gump community of runners or who are running to fight human trafficking and tribe sort of evolved out of that project. I was very closely connected with that journey. But I'm really lucky now. And that lots of the things that I took from the walk, whether it's the nature or exercising, adventure, all of those are a big part of tribes through the events we put on the community we have there that sort of area, the world or area of our customers lives that we're in. And so it's been really fun to still be living in certain ways in the way I was walking, when we're kind of out doing long runs and all that kind of thing.

India Pearson 35:30

Yeah, absolutely. Hold that thought my dog has just broken free. And she's just come to say, Hello, back. Because she's in the kitchen. She just came through the door. So bear with me. Right. Apologies about that. I just saw the dog going. I was like, hello. The show right. That's cool. Anyway, I've got one more question to ask you. Which is the question I asked everybody, which is, looking back at the ripples you've made in your life, what are the biggest lessons you've learned for keeping your mind and body healthy. And I know that you've kind of touched on this just a minute ago. But if you've got any more nuggets of wisdom, you can share with us

Rob Martineau 36:20

the thing probably through tribe and through, I suppose the last couple of years of my life, that's been the most important is almost trying to pass on a baton to other people. And with tribe we, through our foundation, we do something called the hate for freedom project where we support human trafficking survivors to take on their own kind of challenges. Most recently, we've done is the the three peaks, and seeing the impacts. In this instance, it was a group of women that women's lives is so so so amazing. And actually I find it really kind of Naomi in a corny way, but quite like refreshing thing in terms of giving me impetus, because I find otherwise maybe I can get tired of doing some of the things I know are really good for me, but actually trying to always be passing it on and giving other people the chance to do the things that I found so beneficial to me, unfortunately, through tribe and the tribe Freedom Foundation, I kind of have, yeah, we have the chance to do that. So I suppose that would be the thing I'd say.

India Pearson 37:37

Yeah, no. mazing and if anybody listening wanted to find out more about you and and read the book, where where can they find you? And where's where's the best place to order the book from? Excellent.

Rob Martineau 37:51

Yeah, the book should be available at bookstores. It's Waterstones, Dawn's spoils Stanford's Blackwell's see on Amazon and get indeed, and then they want to find out more about me like tribe is a good place to start. There's tonnes of ways to get involved for our events through volunteering at the foundation. So if you google tribe, the tribe Freedom Foundation is it's all there. And we'd love to hear from you.

India Pearson 38:18

Yeah, I love and I love the fact that that tribe has got this you got this other side to it and the community side and I'm sure that you're inspiring so many more people to to get out and move and just embrace the world that we live in. So those amazing and it's been really incredible. Speaking with you today and and hearing firsthand, you know your stories after reading the book. So thank you so much. Thanks so much for having me. It's great. Thank you so much for listening to this episode of the start every podcast. If you'd like to be heard, then please do subscribe and write a review. It helps other like minded souls find this podcast and means you'll never miss an episode. If you want to get in touch then the best place to find me is by Instagram. I'm at with underscore India. Or you can find my wellbeing hub at Ben and flow that is again and speak to you soon.