Common Good Podcast

This Podcast is a conversation about the significance of place, eliminating economic isolation, and the structure of belonging. It's about leaving a culture of scarcity for a community of abundance. This first season is a series of interviews with Walter Brueggemann, Peter Block, and John McKnight. The subsequent episodes is where change agents, community facilitators, and faith and service leaders meet at the intersections of belonging, story, and local gifts. The Common Good Podcast is a coproduction of commongood.cc, bespokenlive.org and commonchange.com

Common Good Podcast

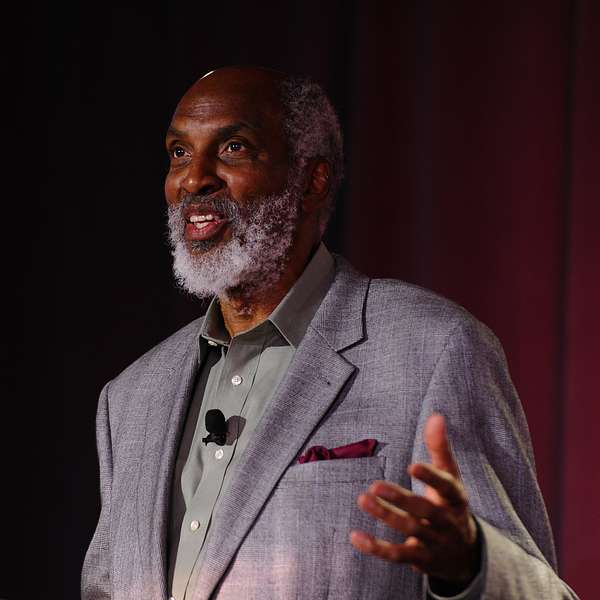

john a. powell: Future of Spirituality & Belonging (part 1)

The Common Good podcast is a conversation about the significance of place, eliminating economic isolation and the structure of belonging. In this episode, Rabbi Miriam Terlinchamp and Reverend Ben McBride speak with john a. powell.

john a. powell is an internationally recognized expert in the areas of civil rights, civil liberties, structural racialization, racial identity, fair housing, poverty, and democracy. He is also the founding director of the Othering & Belonging Institute, a UC Berkeley research institute that brings together scholars, community advocates, communicators, and policymakers to identify and eliminate the barriers to an inclusive, just, and sustainable society and to create transformative change toward a more equitable world. The unique spelling of his name is john’s way of signifying that we humans are part of the universe, not over it.

Excerpts and Works Referenced in the Conversation:

- Story of Moses in the Study Hall of Rabbi Akiva

- Lessons from Suffering by john a. powell

- Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Hariri

- Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson

- Bob Marley - Running Away

- Jerry Butler - Need to Belong (to Someone)

- A Poem in Three Parts: A Story of We

Also, check out our previous episode with Ben about his new book, Troubling the Water: The Urgent Work of Radical Belonging.

This episode was produced by Joey Taylor and the music is from Jeff Gorman. You can find more information about the Common Good Collective here. Common Good Podcast is a production of Bespoken Live & Common Change - Eliminating Personal Economic Isolation.

Well, first of all, hi, John. Hi, Ben. Good to see you again. And John, it's wonderful to meet you. I'm excited about this conversation. When I was thinking about what we could talk about today, especially about the future of spirituality and what it would mean for the three of us to engage around it, I was particularly touched, John, about your work around the connection between structure and story. And so I was wondering if you could humor me a little bit and I could share a story from my tradition and use it as like a launch pad to go from there, if that works for the two of you. Sure. Yeah. Okay. So it's one of the stories that I'm hung up on right now. And I think, especially thinking about the way we gather, the way we connect, the way we think about belonging. And there's a story in our Torahs or our Bible that is about the way it's written. So if you look inside a Torah scroll, it has these little chupachik is a little like drawings on top of the letters. And so in the story, Moses is looking at these letters and it's God who is adding these little additions to the letters. And Moses is like, Hey God, why are you drawing on these letters? It's just about the word that matters. And God's like, no, no, no, Moses. There's going to be this guy, this rabbi named Akiva, centuries from now, who is going to look at every single drawing on top of this Torah, on these letters, and it's going to derive meaning from it. It's not something you and I are doing. It's something like some guy in the future is going to do. And Moses says, well, show him to me then. And so in the story, God transports Moses out into Akiva's classroom several centuries later, and Moses is lost in the classroom. He doesn't understand a word of the Torah being taught. The word is completely different. This is not what he brought. And so he becomes despondent and starts to despair until a student asked Akiva a question. He says, well, how do we know any of these things? And Akiva says, Oh, it all came from Moses at Sinai. I'm really curious about your reaction to the story, but for me. I like thinking that the work that we're doing right now may have an essential or existential truth to it that we're following, but also that in our most exciting, disruptive ways of innovating religion and spirituality, that we're actually crafting things that our ancestors could never imagine, but would see value in any ways in some sort of way. So they don't see themselves, but there's something there. And when we think about the spirituality, I'm wondering about how our stories can connect us to these future things and also what we're supposed to build to support those new stories. So that's a very big, long question. But the first is what do you think of the story? Does it work for you?

Interesting story. So my immediate thought went to what's somewhat of word called hermeneutics. hermeneutics is the science of interpretation or the science of understanding. Under the doctrine or hermeneutic structure, we're always interpreting to understand is to interpret. And you tie that a little bit with some of the stuff we know around the mind science. in the way the mind works. Memories are not what we think they are. You know, we think something happened and it's stored away and then sometime in the future I'll pull it out of storage and look at it and it'll be still what it was when I put it in storage. Memories are largely constructed at the time of the memory. So it's not something we put in storage and then pull out. It's actually something we reconstitute at the moment that we're remembering it. And we we always reconstituted slightly different than it was and sometimes people know that, I mean, they'll get in fights about, no, I was wearing a green hat. No, it wasn't green, it was yellow. And it wasn't a hat, it was something else. And it's not simply that memories are off, it's that people are reconstructing things, bits and pieces, in different ways. And the important thing about memories in some ways is the meaning. associated with him. And the meaning is constantly evolving and being contested. So one of the things I took from the story you shared is that Moses own words were not accessible to him hundreds of years from now. Maybe they may even have been the same words, but as people discussed them, he didn't understand it. And also that the words and the drawings are in relationship with each other in a dynamic way, I could say a dialectic way. So I think that in terms of our spiritual practice, one is being open to, from my perspective, it's never categorically set. It's not like a stone or a piece of furniture. It's constantly Engaging, changing, and transforming the environment that is, and the context that is being shared in. So to me, part of spirituality is sort of the openness to the movement of life and the meaning of life. And to me, partially, the story reflected that in terms of Moses going centuries into the future and not recognizing maybe his own words.

It's really powerful to me to hear you share about that, John. And the thing that really stuck out with me around this notion of memory is that we constituted at the time of remembering and the ways in which we're guided by these stories that have been given to us. And yet we're creating stories that hopefully we'll be giving to others in the future that help to guide us around our way. And my reaction to the story of Miriam is very much so rooted, I think, in this notion that We are all a part of one story, and I think it is humbling to me to recognize that you are just a part of the story. You're contributing to it, you don't own it. But that you get to play a part and recognize that whatever it is that we're putting into the ether it's going into the ether with what others are putting in there as well, and that there is a new spirituality that's coming out of it and as John was talking, you took me back John to a time when we were in Cuba, I got a chance to pal around with you and we were sitting outside this little Cuban cafe having lunch. And I remember you were talking then about this notion of how spirituality and different stories serve people for different times. But at certain points, their story stopped being able to be the moment that their needs were manifesting. And, I'm just really curious, you know, as I was listening to you, What are the new stories and what is the role? What is the new spirituality that we need and what are the things that we probably need to say now that maybe a hundred years from now, like you're saying, Miriam, we might sit in the classroom and be like, well, I don't know that that's actually what we meant, but there's something that needs to be said now in the face of the challenges we have, because it does seem like a lot of the spirituality that we're trying to practice seems to be coming up short.

Think of the word re member. Re member. Putting stuff together, that's important, not just in terms of spirituality, but in terms of history, politics, in terms of our being, is re tell stories. and remember the past in order to help constitute the future. And so it's not just a question of getting it right. I mean, we shouldn't be fabricating for sure. It's more complicated than that. And what we're really trying to do is sort of give some shape to possible futures. And one of the things that's clear to me, Dan, in terms of spirituality and religion, frankly, is yes, it's religions and spiritual practices come in response to some collective need that we have at a particular moment, particular place, particular time, and our needs are not static, I think what we need now is, frankly, a lot of what you're doing. My brother, when he returned from the Marines when I was a kid, about probably 10 12 years old, and he was very heartbroken. He used to play this Jerry Butler song, Need to Belong. And it was a love song, but it was actually more than a love song. And one of the Persons was, excuse the sort of gender aspect of it, but a man needs to belong to someone. A man hates to be known as no one. even though he's singing in the context of a love song, it's actually a spiritual statement that we all need to belong. And we need to belong to each other. And when we don't belong it's a very sad state. And part of the challenge now in terms of spiritual practice is, how do all the different expressions of humanity and life on the planet, how do they belong to each other? Because our traditional spiritual practices from 100, 000, 2, 000, 5, 000 years ago was very discreet. My group belongs, I'm only concerned about my group. And the other group is fodder for whatever. And it wasn't just a way to organize spirituality, it was a way to organize society. Most people didn't matter. Literally go back 5, 000 years ago and essentially the whole world was enslaved in some various forms with a few exceptions. Well, that's not the world we want to inhabit now. What's the story? What's the spiritual practice? That we need to embrace and then the work that I think you do and we're trying to do as well. I think it's the work of a world where everyone belong and no one is other. And as powerful as that is. I don't think we have Flushed out stories, practices, and a spiritual tradition that deeply holds that. And so I think that's part of what our work is.

I think there's something about our story and also the institution or the structure that's going to hold the story in a way that would continue to convene and connect and build some kind of tissue. I want to talk about that. But before leaving this part moment to go to the next moment, I'm curious about the way the two of you see story and belonging and tribal identity as it relates to all of humanity. I'll speak completely for myself in this moment that I'm struggling right now with my own tribal connection and our collective memory, how it relates to our collective trauma and then also for the shared love of humankind and that right now with what's happening in Israel and Palestine. All of a sudden. It feels like all of a sudden, even though it's not all of a sudden, but right now it feels like all of a sudden that my tribe is being called in to account for all kinds of things while also holding this truth of a collective trauma that predates this moment, right? And so if you're being told all your life, don't trust assimilation, don't trust that you belong, that no matter what you look like or sound like, you'll still be Jewish in a world that hates Jews. It gets really hard, I think, to speak beyond that circle of pain and fear in order to live a dream of a collective future around humankind and not just your identity. I'm curious if you two struggle with that of how you see us getting our story in a way that gets us beyond that moment of galvanizing around our own pain and hate and fear and a place of promise and possibility.

You know, my personal experience brings me to the story as that being difficult to me. That's a part of the work that needs to happen when I think about belonging. I feel like belonging. It's not about disappearing the beauty of tribal identity and connection. I really appreciate it when John's talked about the bonding work that needs to happen outside of the bridging work, whereas like the bridging work happens across difference and the way that I've kind of held some of his languages at the bonding can happen within sameness, there's work that we do in our tribal identities that really strengthens us, fuels us, connects us, heals us. But I, I do think it's real work to figure out how to actually write a new story that has more characters and a greater alphabet than the trauma that we brought to the initial writing sequence and not to keep beating on this Cuba drum when we were there. But as I'm looking at John, that's just what keeps coming up for me. There was something you said to me, John, that, that I've come back to over and over my mind and in conversations when we were there also, which was, we were looking at our Cuban relatives there, who, from my racial construct, I would see some as black, I would see some as mixed race or colored and some as white because of my own language, my own alphabet, my own trauma. And yet when we were there, what was striking was that the black Cubans prioritize their cubaness over their blackness and it was very disruptive for me because they were proud of Cuba and John asked me a question and I wondered what story we would have to have as black Americans. Some of us who are still struggling to think about having pride to be an American rather than clinging to my blackness alone as the way in which I think about my identity. And I think it's it's about you not just healing from the trauma, but I think learning how to understand oneself and one's own tribe beyond the trauma of genocide, pogroms, enslavement, all of the different expressions of violence. But I think it's difficult because it takes a lot of bravery. Courage. You need a lot of support to do it. I'm not sure I have a great answer around that, but I have seen in my own life that that's a part of the work. I'm still working on how to talk about myself in the world in a way that's not rooted in the trauma of my ancestors being taken and brought, from Africa to North America. But I think it's the work that we must be on so that the world we shape does not just continue to be a caricature for the world we inherited.

Yeah, I think, Mayor, I think that's a very important question. I would reframe it in some way. Not that the reframe will necessarily take us to an answer, but I think it might help in some respects. So a couple of things I would say, in today's discourse, we talk a lot about tribes because of the fracturing and the patriotic and the fear and the trauma that the world is experiencing. And that impulse, that language is on the rise everywhere, not just in the Middle East, but everywhere but then we go back to look at tribes. What we find is that our understanding of tribes and the way we use it today is somewhat problematic. Most people agree, there's some disagreement, that tribes were generally no bigger than 150. Most of them were probably smaller, why do I say that? Well, if The predicate of a tribe was that these are people that you lived your whole life with. in a sense you live communally with. You live with them. You didn't hear about them, for the most part. You didn't read about them, for the most part. It's not like your cousin so and so who lives in England that you never met. These are the people that you move through life with your entire life. And that intimacy is what created the impulse of what we now call tribalism. So when we describe Jews, the twelve tribes, as a tribe. We're not talking about it in the same way that we talk about tribes from prehistoric times. because you don't know most of the people who are designated as Jews. I don't know most of the people who are designated as black. We're talking about millions of people, most of whom you will never see. Now, why is that important? When we talk about tribe, first of all, It's complicated in a lot of ways. We're usually making reference to Indigenous people and oftentimes, it's a sense of pre modern and not civilized in some respect. The violence that we visit upon each other is probably much more an expression of modernity than it is of tribalism so we're conflating two different vocabularies, if you will, and we're doing it in a way that actually locks us in. Because we think of tribes as the way we use it today is that we're evolutionary program to behave a certain way. And for thousands, if not millions of years, this is where humans live. And we bring that into the moment. Humans didn't live along racial, religious, ethnic lines for thousands of years. That's a new phenomenon. And to understand that phenomenon, we need a different vocabulary. And Harari in his book, Homo Sapiens, helps us with that sum. And he says, how did homo sapiens actually end up, if you will dominating, if not defeating Neanderthals. They existed at the same time. The current reading is that Neanderthals maybe were actually had bigger brains, were bigger bodies and faster than Homo sapiens. So if there's a contest between them, we might expect Neanderthals to win. Well, what Harari and others suggest is that what allowed Homo sapiens to win is that Humans, at some point, developed the capacity to tell stories and the stories humans, homo sapiens told, allowed homo sapiens to constitute a larger we, and so instead of 150 going up against another 150, which if that happened in the context of homo sapiens and Neanderthals, Neanderthals would probably win. But now Homo sapiens were telling stories that allowed them to actually see themselves in thousands of people. And so they had much bigger communities. They had larger weeds that was constituted through the story. O'Reilly continues to spin that, he would say, he's Jewish himself, but he would say Judaism and Christianity, these are stories that allows us to see some similarity among people who will never see, who speak a different language, who eat different food. Again, why is that important? We are capable of developing new stories. We're not locked in those stories. We have histories, but we also have futures. We also have possibilities and we have imagination. So the last thing I'll say, and Mary, your question is too big to answer in a short period of time, maybe even a long period of time. But As Ben suggested, and I've written about this in an article called Lessons from Suffering, trauma is a certain kind of suffering, and it has to be attended to. But the goal is not simply to get away from suffering. The goal is not to be completely safe. Those are not only false goals, they're unattainable. And not only are they unattainable, when we take that stance, we can't learn from the suffering. Now, are learning from the suffering, the question is, what do we learn? Do we learn to be afraid of everybody? Do we learn that As Bar Maliwa says, every man thinks his burden is the heaviest. To me, that's one of the toxic things that's happening, frankly, now in the Middle East and around the world. Every person knows about their suffering and thinks their suffering, every man thinks his burden is the heaviest. And so part of it is not to ignore. As some would have, the suffering of black people, enslaved being pulled here three or four hundred years ago, it's not to ignore the pokrom of Jews being harassed all around the world and the genocide, but it's not to ignore the displacement of Palestinians, it's not to ignore any of those pains, but to see that there's something in those pains that actually could unite us. So instead of using the pain just as a function of creating a false safety, and a false evidence, we could use the pain to learn. And in the article I actually wrote, I talk about many of the major religions. there major lessons come from pain? And so I don't think we ignore the pain. I don't think we try to get rid of it. I think we learn from it, but we also learn that not only our pain, whatever that means, but your pain as well. And so I think the toxicity of the moment is not the pain per se, it's not even the trauma per se, is to make my pain the only one that really counts. Make my story the only one that really counts. And so I would say as I tell the black story, I have to tell it in relationship to other stories as well. And I think as you tell the Jewish story, you have to tell it in relationship to other stories as well. I think that's a way forward.

And John, what you just said, I found so beautiful and it also made me sad because it feels like such a requirement of faith in these folks that we don't know but identify with, right? Like the people I'm proximate with, no problem. My neighbor, I disagree with almost every political view he has, but you better believe like armageddon comes like that's the guy I want like I want to go to his bunker Like he's got it and i'll be welcoming it because I pick up his kid every day and I make him banana bread and We're neighbors like true true Proximate intimate neighbors like you talked about i'm not worried about anyone that I actually am in relationship with i'm worried about The burden of carrying the stories of ancestors and my people and my tribe and, and the way you described it, I don't know yet at this moment when things are so hot, how to sit at a table and say, all of our pain has weighed at this place, and therefore, so does our dream of what's possible. Do you know how, either of you, when you get around those tables, how to cultivate a sense of intimacy in a way that makes it feel like we can actually dream together and that we are equal weight and that we're not just sort of comparing ourselves. I don't really know how to do that when it's really hot.

Well, one thing I'll say, we have different skills and different talents and we're called to do different things. But a good story and a good storyteller, that's exactly what they do. And so, Isabel Wilkins, whom I had the pleasure of interviewing when she wrote a book, The Warmth of Other Suns, about the Great Migration. And it's about, frankly, Black people largely migrating from the South, thousands, millions. But she tells the story, she does it in such a beautiful way, that people who are not Black, people who maybe migrated from Ireland, they see themselves in the story. The story itself becomes a bridge. And so there's a way of telling a story that excludes everybody else, and I think we have to be careful of that. And there's a way of telling a story that this in fact is human suffering. We all suffer. We all suffer. So, you know, I refuse, and you can call me a name or invite me to your house, but I refuse to say that one child's life is better than another. So what if the child is Palestinian? What if the child is Jewish? I have children. And I would die for my children in a heartbeat. But I think many parents feel the same way. And even though I would die for my children in a heartbeat, I can't really say that my children are more important than Ben's children. So, Miriam, you said how to say it? Say it. And say it. Not out of some sort of abstract thing, but out of people's real experience and love. These stories about the other are just that, stories that have been given to us, that we've inhabited. And I always say, reject them. There is no other. It may sound strange in this world where othering is the international sport of choice, but for those of us who believe and want to call it to give birth to a world where everyone belongs. We have to actually say, say it and mean it. And it doesn't mean that I'll know your children as well as I know my own. But again, you have that intimate connection with your neighbor because you see him or her day on a daily basis, but what about the neighbor in Jerusalem that you'll never know? what holds that together is a shared story. We can create, we have to create, we're meaning making animals. We have to make meaning that brings us together. We have to tell stories, and you talked about structures. Think about something like segregation in the United States, or apartheid in South Africa. These were structures to keep people apart, because the powers that be sort of understood that if people really are allowed to come together, something magical might happen. So keep them apart, and when they have to be together. We have rules. No touching, no dating, no doing this, no being friends. So that's the negative. What's the positive? There's a controversy brewing right now because, the United States military in many expressions are saying not only in their advertisement, but in their practice to people different races, different ethnicity, different backgrounds, you belong. You belong in the military. This is the place where you belong. And they're going more than just a slogan. And some people say, you can't use the military. They're terrible. They're death machines. But life is complicated. They are telling the story that we need to tell. And if we don't want them to tell the story, we have to tell it. but belonging is real. And I say we're born physically attached and spiritually attached to another person. Without that we don't survive. And we may cut the umbilical cord, the physical attachment at some level, but we should never cut the spiritual cord.

I'd quickly say alongside John's invitation of telling new stories that there also are some behaviors that we can lean into with those new stories. One of those things is to build a bigger table. In the face of the conflict that was happening with Black people and police in 2015, 2016. It's one of the first times I heard John in person speaking and I was challenged by this idea of, we need to build a large enough table for everyone's suffering. So to me, it's this notion to say, instead of fighting for who has room at the table, how about we build a bigger table? And to me, the behaviors of that as I've talked with folks is how do you design spaces that are actually designed in such a way to bring more perspectives than the perspectives people are proximate to into this space? And then how do we develop new norms? In terms of how do we show up in these spaces where we actually start adopting norms of not just sharing, but also listening norms of pausing norms of practicing curiosity, what does it mean to come to a bigger table, recognizing that 80 to 90 percent of what's going to be said at that table, you vehemently disagree with. But how about you listen for the 10. And instead of making the 80 to 90, the focus and the reason to break, you look at that 10 to 20 and see that as an invitation and an opportunity to bridge. And from that, can we develop somewhat of a new kind of micro social contract for moving forward? We find ways to continue to build these bigger tables, function with these new norms and come up with these new micro social contracts that say. We can actually bridge and build some new structures together, and we're holding the reality that we are going to disagree because we're different people coming from different worlds, but the social contract is about what happens when we disagree, that we make the commitments that I'm not going to other you, you're not going to other me, I'm not going to be violent towards you, you're not going to be violent towards me, and we've got to figure out some new norms and practices around handling disagreements about really real things. People's lives being at risk. But, you know, I don't have the answers for it. And I actually don't think Too many of us do. I think the answers for that actually lie at the bigger table.