The Global Novel: a literature podcast

The Global Novel is a podcast that surveys the narratology of world literature and history of translation from antiquity to modernity with a critical lens and aims to make academic education in literature accessible to the world.

The Global Novel: a literature podcast

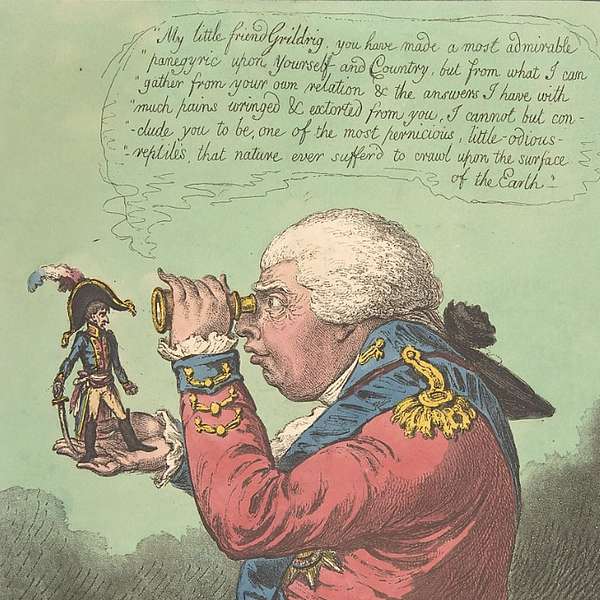

Gulliver's Travels (1726)

Gulliver’s Travels remains one of the finest satires in the English language, delighting in the mockery of everything from government to religion and —despite the passing of nearly three centuries-remaining just as fun, funny and relevant today.

Our guest-speakers are chief editors of the 2023 Cambridge Companion to Gulliver’s Travels Dr. Daniel Cook and Dr. Nicholas Seager. Daniel is an Associate Dean and Reader in English Literature at the University of Dundee whose teaching and research interests include eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literature. Nick is Lecturer in English Literature at Keele University, UK. His research interests are Restoration and eighteenth-century literature.

Recommended Readings:

Johnathan Swift, Gulliver's Travels (1726)

Cambridge Companion to Gulliver's Travels (2023)

This podcast is sponsored by Riverside, a professional conference platform for podcasting.

Subscribe at http://theglobalnovel.com/subscribe

Comment and interact with our hosts

Buzzsprout - Let's get your podcast launched!Start for FREE

Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase, I may receive a commission at no extra cost to you.

The adventures of Lemuel Gulliver's are the stuff of legend. First he is shipwrecked in a strange land and finds himself a prisoner of the tiny inhabitants of Lidiput. He then washes up in the country of Brobdingnag, where the people are giants of extraordinary proportions. Further exploits see him stranded with the scientists and philosophers of Laputa and meeting a race of talking horses who rule over bestial humans. Gulliver's Travels remains one of the funniest satires in English language, delighting in the mockery of everything from government to religion and, despite the passing of nearly three centuries, remaining just as fun, funny and relevant today. Thank you for tuning in to the Global Novel. I'm Claire Hennessey. With me today are chief editors of the 2023 Cambridge Companion to Gulliver's Travels, dr Daniel Cook and Dr Nicholas Seeger. Daniel is an associate dean and reader in English literature at the University of Dundee, whose teaching and research interests include 18th and 19th century literature. Nick is lecturer in English literature at Keele University, uk. His research interests are restoration and 18th century literature. Welcome to the show, daniel and Nick.

Speaker 1:Great to be here. Thanks for having us. Yeah, indeed, thanks.

Speaker 2:Well, to begin with, what do you think Jonathan Swift's intentions were in writing Oliver's Travels?

Speaker 1:Great question. It's always a difficult question with a satirist, especially such an experienced satirist as Swift. You know he's mocking everything and everyone. Very famously, he said he claimed that he wanted to vex the world rather than divert it. With this book in particular, he wanted to challenge our assumptions assumptions, our cherished uh institutions, if you like. Nothing is off limits. He attacks everything and everyone. But at the same time, though, I would kind of quibble with what swift says, because this book is very diverting, it's very entertaining, it's very funny, it's full of farce, it's full of humor. It's also got its very serious intellectual side as well, but that's why it's such a brilliant book. It's full of humor. It's also got its very serious intellectual side as well. That's why it's such a brilliant book yeah, I'd agree.

Speaker 3:I'd say that, um, it's easy to overlook that gulliver's travels is a supreme work of the imagination. Um, as you said, claire, um swift imagines these worlds in which um gulliver is either um a 12th of the size of the inhabitants or 12 times larger than them, and then he goes on to all kinds of strange and wonderful worlds and encounters rational animals. So it's a great work of the imagination, it's a great adventure story and that's why I think it's had such an enduring appeal, especially amongst younger readers. So God of War gets into all kinds of escapades due to physical differences or other kinds of ways in which he's made vulnerable in these strange new worlds. But he did also.

Speaker 3:But Swift did also have some serious points. He wanted to challenge the premise that humans were entirely rational creatures, the idea that the world revolved around humanity in some respects, and it's important for de-centering people from the world in which Gulliver operates. And I don't think we should also entirely overlook the fact that Swift probably you ask about intentions. Swift knew that this would be popular. He knew that this would be a fantastically successful book because it is so readable and enjoyable and it was a huge commercial hit at the time.

Speaker 2:Right. Well, how was it received? We know that Swift knew the book would incite much controversy, so he published it anonymously, right?

Speaker 3:Well there's. I won't get the quotation quite right, but Swift's friend, John Gay, told him that it was being read everywhere, from the nursery to the cabinet council, and that's remained true largely today. So the one thing to say about the reception is that it was very, very popular. It was an expensive book for its time. It was in two volumes. It was eight shillings sixpence, which is quite a lot of money. Not a lot of people could afford it, and so it was popularised through abridgments and through serialisations. People were dead keen on it, so in some sense it was a huge success. In other respects, as you've said, it was also a very controversial work.

Speaker 3:There is a lot of satire in Gulliver's Travels which seems to be directed against particular people, and Swift and his friends were worried about how that would go down. In some respects it's written in a way to be quite guarded against that, both in the sense that it was published, as you said, anonymously, and he took great pains to cover his tracks and get back to Ireland as quickly as possible after having delivered the manuscript in London, or at least having it delivered by his friends in London. And he also took pains to make sure that people couldn't read it as a narrow, particular kind of topical work, that it had a series of bigger, more universal themes. That said, in the wake of Swift's death, some of the people who write about him straight afterwards, including his own cousin, find parts of Godulliver's Travels quite hard to defend, especially the tendency towards the kind of misanthropy in Gulliver's Travels which remains debated to this day. But certainly there is a kind of moralistic backlash against Gulliver's Travels that sits alongside its huge popularity and the relish that people clearly had for it.

Speaker 1:I think Nick puts it really well and I think even nowadays we kind of struggle with books that are popular straight away. It was a bestseller, it was out of print within weeks of publication and a very expensive book as well Two volumes, as Nick says. I think critics, particularly with great literary works, kind of struggle with what to do with a popular text. Um, and as Nick says, it was abridged very quickly, it was. It was bolderized very quickly, um, pirated very quickly, translated into multiple languages fairly rapidly. But what I find fascinating about the sort of origin stories of Gulliver's Travels, as it were, is it's kind of unlikely here to many ways. It doesn't have Jonathan Swift's name attached to it, so by then he's a very famous, very prominent satirist. So it would be very easy to publish this work as a work by Swift, notwithstanding the controversy surrounding it.

Speaker 1:There are some quite aggressive gestures in the book, as it were. There are even hints of attack on the late Queen Anne, for example. There's a lot of libelous stuff here and it's published as Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. It's not a very glamorous title, so it's unlikely hit in many ways, but I think, as Nick said earlier, because of its fantastical elements, its very clear satirical drive, it cannot help but be the success that it was amongst critics and general readers.

Speaker 1:It feels like a slight sort of underdog story in many ways. It isn't sort of heralded as this sort of great beacon of literature at the time, but it just shows that it stands the test of time and again. That's slightly unusual for satirical works. Satirical works tend to be so focused on the politicians that swift was attacking, criticizing, exposing, for the hypocrisy were dead or they were out of office, they were out of power. But there's just something quite universal about this kind of story. So it's very particular but also very, uh, universal as well. I think everyone sort of recognizes themselves or people that they know, or people, people in the public eye, in this text. So it's got a lot going for it, despite the very sort of quite frifty, quite banal title page in many ways.

Speaker 2:You know, what I truly love about the Cambridge Companion is its feminist and post-colonial reading of the satire. Critics have frequently characterized the narrative as misogynistic and stressed its negative representation of female physicality. What can we learn from Liz Bellamy's essay collected in this book that truly offers a new reading with this perspective of body and gender.

Speaker 1:Yes. So Liz Bellamy's got a fantastic essay in this collection. It's fantastic because she takes stock of fairly long-standing debates about the perceived misogyny of the text. And Liz, quite rightly, is clear that there is clearly misogynistic language in the text. The question is is Swift being ironic? That's a standard satiric defense, and so on.

Speaker 1:We certainly have very problematic depictions of the female body. It's rendered quite monstrous in Brumlingnag, the Land of Giants, where we have these sort of large, hairy, unattractive, unassuming female bodies hairy, unattractive, unassuming female bodies. There's also a sense that some of the characters have cancerous breasts and so on and the breasts are rendered sort of ludicrously large and there's something about sort of the grotesque female body, if you like. But Liz and another critic have sort of begun to realise that Gulliver himself is gendered and his view of the monstrous female body is, at least in part, a critique of his own monstrous masculinity, that he has these preconceived notions about female beauty and so on. So at quite a literal level, his view of their monstrosity says more about him than it does women, if you like.

Speaker 1:It's also worth pointing out. I think that we've touched upon how this book talks about religion in quite complicated ways. This book is also full of commentary on modern science, particularly for what, for Swiss generation, was a fairly new invention, which is the microscope, and there is a sense that the female body is rendered in such a monstrous way, because this is Swift critiquing or inviting us to be quite wary of microscopy. You can suddenly see God's creations in all of it in such a close way and, metaphorically and literally, it will horrify our perceptions, and so on.

Speaker 1:So it's misogynistic insofar as he's using the female body as a means to critique modern science, the science of the Royal Society and so on. Or you could say, as Liz does in her fantastic essay in this collection this isn't just about female bodies, it's about male bodies as well, and we tend to ignore the latter. I think that's why this is going to be such an influential essay, because it takes stock of the debates but just pushes it into that new direction which I think is so exciting.

Speaker 3:Daniel's exactly right that the book is full of very problematic representations of female behaviour and female bodies. So in Lilliput the women are caught, are a bunch of troublemakers, scandal mongers, you know, thrown to infidelity and all of those sorts of things causing men to fall out and so on and so forth Classic kind of misogynistic sort of portrayal. Then we get into Brobdicknag and Gulliver describes with this kind of disarming candour the bodies that he experiences. But so much of that kind of grotesquery, which is a kind of traditional form of satirical prose that he kind of adopts and extends from the French 17th century writer Rabelais. So much of it centres on the female form in particular, and especially kind of sexualised female bodies that are not attractive but instead are disgusting, either because they're smelly or because they're hairy or because, um, you know that he can see too closely, really, and it's absolutely right to say that swift might be wrestling with philosophical debates about kind of perception and proximity. Um, logically speaking, um, I mean to give another example that when he finds, after he's been in Brobdingnag for a while, that when he meets people of his own size, he's shouting at them all the time, because he needs to shout in Brobdingnag in order to be heard. So the idea is that he has this kind of hypersensitivity to the smells and the sights in Brobdingnag, but so often it does centre on the female form, which is this kind of sight of, of monstrosity.

Speaker 3:I suppose a really interesting moment in light of what liz writes is in the final part of gulliver's travels, um, and it's it's a rightly notorious um episode where um gulliver um is amongst these reasonable and rational horses and there's a society of sort of humanoid, kind of bestial humanoid figures called yahoos, which are sort of presided over by the Wynnims to some degree, but which are ultimately just kind of intractable. They're not domesticatable animals in any kind of way, shape or form, but they are basically human, and Gulliver is trying to take every measure he can to prove that he's not one of these things, but one day, when he strips off and has a wash in a swim in LA, he's assaulted by an amorous yaku, which is kind of the horrifying degree of what swift is imagining, you know, an 11 year old girl, um, and in some respects it kind of extends that sort of attack on libidinous femininity to some degree. The product of it, ultimately, though, is to confirm in gulliver's own mind that he is this thing called a yaku, and so the, I suppose, misogyny becomes a kind of self-hatred. So, as Liz gets that so powerfully, it is also about vulnerable masculine bodies In all kinds of ways.

Speaker 3:When Gulliver is in positions of vulnerability, his is a body that is feminised as well. He's made a pet or a plaything or a toy or a doll, in Rob Dignac in particular, where another young girl who he describes as his sort of nurse Lundelklitsch, looks after him. And again it's this kind of slightly uneasy, not just in terms of gender relations but also in terms of age, because the dynamic there is kind of curiously parental, filial, but also somewhat sexual. And when the young women at court in Brodnick, like the maids of honour, get hold of Gulliver, he has lots of of descriptions that you know I'm trying to kind of choose my language a little bit carefully here, but he's effectively used as a kind of sexual toy in all kinds of ways. So yeah, it's a great chapter for me about the ways in which bodies are gendered in Gulliver's travels. In general we cannot skirt or shy away from the misogyny, but it's kind of part of a bigger kind of set of questions about humanity, I suppose and about the physical experience of occupying a human body.

Speaker 2:Right. As you both have highlighted Gulliver's role as a traveler and observer, reflecting the intersection between literature and science from feminist perspective, could you also share more on how this intersection between literature and science is sketched against the backdrop of Britain's colonial ambitions and the pursuit of knowledge during the early 18th century?

Speaker 3:I suppose God of Earth Travels is written at a point in time where we're kind of at the end of what we might think of as an age of discovery, where all kinds of new worlds are still being discovered, of course and I use discovered in a kind of, you know, cautious sense, because of course these worlds are not discovered to the people who were originally there, but from a sort of Eurocentric point of view it's perceived to be a kind of an age of discovery, an age of enlightenment, an age where European sailors were going out and finding out more about the world and of course the accounts that were coming back home were tinged with that sort of um, eurocentrism, um. So what we have, and I think what we have exposed in gulliver's travels, is a kind of a rhetoric of discovery and a rhetoric of intercultural encounter that parades as this sort of objective and empirical kind of account of things. You know, I landed here. It was this sort of temperature, it was in this latitude, it was an island about this big I. I went up the shore, I, it seems very factual, very driven by, um, the kinds of writing being encouraged by what's referred to as the new science, this 17th century scientific revolution um, with the, the royal society founded in the 1660s at its head, encouraging this kind of way of describing the world, this kind of objective, fact-oriented, descriptive kind of approach to the world.

Speaker 3:On the one hand um meeting palpable, fantastical, crazy stuff um, you know, he meets um giants, he meets miniature people, he meets um kind of talking horses, he sees flying islands and all the rest of it, so that it's kind of in some respects we can understand Gulliver's travels as sending up this kind of combination between a sort of scientific way of apprehending reality and the sort of imperial mindset that that promotes as well.

Speaker 3:So in all kinds of ways, when Gulliver encounters people in foreign worlds, the descriptions are racialised in all kinds of ways. So he's drawing on travel books, he's drawing on earlier works that do describe peoples from other cultures, and a lot of that filters into Gulliver's travels as well. But in some respects as well, gulliver becomes this spokesperson for a kind of narrow-minded I'd say not just British but English kind of superiority which is constantly sent up until it's utterly dismantled, and he ends the entire book by A wishing that the Wynims would actually sail over to Europe and start taking over. He kind of wants this kind of counter-colonialism and also he has this long diatribe against the colonial mindset, against the idea of swooping into another country and taking over. So the book is not innocent of trends within early modern and 18th century imperialism, but it can certainly be read in all kinds of ways. There's a backlash against those.

Speaker 2:If you have enjoyed this episode so far and desire to listen to the entire episode where Daniel and Nick talk about Swift's criticism of politics and religion in the satire, as well as genre and narrative techniques, be sure to subscribe at theglobalnovelcom slash subscribe. Thank you so much for listening.