Positive Leadership

Positive Leadership has the power to change the world. By focusing on trust, empathy, authenticity and deep collaboration, leaders can energize their teams to achieve success for individuals, their organizations, and society as a whole. Yet, it remains relatively unknown outside positive psychology and neuroscience circles.

Join Jean-Philippe Courtois, former member of the Microsoft senior leadership team alongside Satya Nadella and co-founder of Live for Good, as he brings Positive Leadership to life for anyone in a leadership capacity—both personally and professionally. With help from his guests, Jean-Philippe explores how purpose-driven leaders can generate the positive energy needed to drive business success, individual fulfillment, and societal impact across a range of industries—from technology and social enterprise to sports and coffee.

Most importantly, you’ll learn practical tips to apply in your own life—so you can start making a positive difference in the world.

Positive Leadership

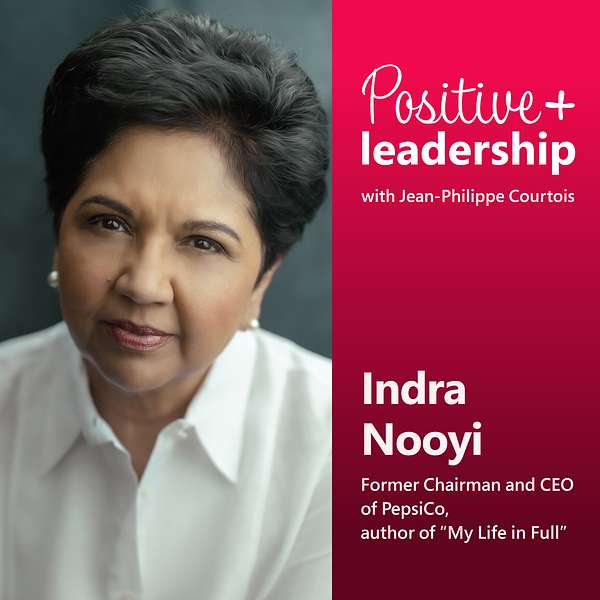

Driving performance with purpose (with Indra Nooyi)

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

Indra Nooyi, the former chairman and CEO of PepsiCo, is one of the foremost strategic thinkers of our time.

She shattered the glass ceiling of corporate America and wrote many of the rules of behavior along the way.

Learn about her distinctive leadership mindset on the latest episode of the Positive Leadership podcast with JP.

Subscribe now to JP's free monthly newsletter "Positive Leadership and You" on LinkedIn to transform your positive impact today: https://www.linkedin.com/newsletters/positive-leadership-you-6970390170017669121/

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Hello and welcome to Positive Leadership, the podcast which helps you grow as an individual, as a leader, and ultimately as a global citizen. I'm super excited to share today's episode with you. My guest, Indra Nooyi, the former chairman and CEO of PepsiCo, is one of the foremost strategic thinkers of our time. The first woman of color and immigrant to run a Fortune 50 company. She shattered the glass ceiling of corporate America and she wrote a lot of the rules of behavior all along the way. Not only did she rise to the top of PepsiCo, but she helped transform the company by spearheading the development of new healthier product lines and running the business on the principle of performance with purpose, a corporate mission with three main goals.

INDRA NOOYI: The first was a portfolio transformation. Second was a focus on the planet, but sensibly, only what affected our business and drove shareholder value. And the third was creating a different environment for our people. And each of the activities in these three planks directly linked to shareholder value, because if we didn't deliver on that, we couldn't deliver performance. It was a sensible way to marry output and outcomes, performance and purpose. That's really what it was.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Back then, in the early 2000s, purpose around public sector businesses was pretty unusual, and Indra played a key role in expanding our understanding of purpose in relation to companies. Today, she's a New York Times bestselling author for her memoir, "My Life in Full: Work, Family and Our Future," and she continues to inspire leaders worldwide with her dedication to ESG. It was such an honor to have her on the podcast. In this candid and deeply engaging conversation, she shares her top tips on how to make a meaningful impact, how to tackle sexism and racism head-on, and the importance of guidance and support in professional growth. This episode is packed with practical advice and wisdom. Make sure you stay with us until the very end. Indra Nooyi, a very warm welcome to the show. Thank you so much.

INDRA NOOYI: Jean-Philippe, thank you so much for having me on this program.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Indra, in your book, you paint a vivid picture of family life growing up. And what struck me was the repetition and consistency, which must have felt very grounding for you. So can you talk a bit about your family life growing up? I know your parents and extended family influenced and inspired you. What lessons did you learn growing up that have been invaluable to you?

INDRA NOOYI: I was born a few years after India got independence. And this was a time in the mid-50s when there were no computers, no internet, India had no television, they had a few radio stations, and anything from overseas came either through the BBC or Voice of America. So it was a different world. We got all our news by going to the library or to the US consulate or the British Council libraries. And our view of the world was guided by what we read in those magazines and what we were taught in school, as the teachers decided. And so it was a very sheltered existence. As girls in the family, growing up in the south of India where it was pretty conservative, in those days, in most families, the boys were educated and the girls were not over-educated because the belief was if you were over-educated, nobody would marry you. But I was in an unusual family where my mother, father, grandfather, everybody believed that women should be given an equal chance as the boys, as long as you have the aptitude for it. And so we were encouraged to study as much as possible. We were given all the help at home to navigate through difficult subjects. And we were never held back because of our gender. However, in this family where everybody got together all the time and accepted each other for our issues, our life was about spending time with each other because we had nothing else to spend time with. We figured out games to play. We made up games because we didn't have too much money to buy games. And there weren't so many games in the marketplace. Our life was about one foot on the brake, one foot on the accelerator. That's the way I'd say it. A brake in terms of you will live within these social norms, the accelerator, dream big, you can be anything you want to be. So I think in many ways, I won the lottery of life. And in many ways, I am a product of that upbringing, which might sound a little restrictive, but I think it was glorious in its own way.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: It's wonderful to hear, but in a way, I mean, the way you framed it, Indra, I don't know if it's the luck, but the opportunity you had through your parents to get educated, because I think at the time, probably you were one of the few, right? It was quite rare for girls to go all the way to higher education the way you did.

INDRA NOOYI: That's right. In fact, I was surprised that my parents allowed me to go out of Madras as a single woman, first to Calcutta, but then the bigger shock was when they actually bought me a ticket to come to the United States. And again, I use this word, “winning the lottery of life” judiciously, because I was lucky. My parents could have stopped me any time, and they didn't, they gave me tailwinds.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: So let's build a little bit on that kind of family life and what you learned through that discussion with your parents, grandparents, I mean, all of your brothers and sisters as well, and some of the skills you've acquired at the time. I think I heard you talking in a number of shows about the art of debating. And I believe you attribute actually a lot of your later success to that skill of putting forward your case and bringing people around you, around the way of thinking, your way of thinking. So can you tell us more about this skill and how positively this impacted you in your life?

INDRA NOOYI: You know, I went to a Roman Catholic school in Madras, in Chennai, Holy Angels Convent. And at that time, the nuns from Ireland were still there teaching. So it was wonderful to have those nuns there who invested in two things. One, they said, "You all have to have the right diction and the way of talking." So they took a few kids under their wing. We happened to be -- my sister and I were both a year apart in the same school -- we were one of the few that the nuns picked because we were sort of bustling with eagerness to study. And the nuns taught us how to speak. Diction, not in a sing-song way like we do with the Indian languages. They really helped us with diction. And the second thing they said was, "You've got to be able to listen and articulate points of view. You've got to listen to differing points of view and articulate a point of view." And the school had an outstanding debating team. And first it was elocution competitions, and then it was debating teams where you had to argue for or against, leading all the way to sort of impromptu debates where you'd go to a debate, pick a topic from a bowl and start to talk. So it was difficult times, but you had to read and be aware of issues all the time because you never knew when a topic was going to be thrown at you that you had to make a case for. And when you went into debating competitions, you had to show confidence, mastery of the subject. You had to be clear in your articulation of ideas and be precise. And so that's a skill that I think every leader needs to have. And I think in many, many ways, that skill was developed, honed and fine-tuned, starting with my debating days in Holy Angels Convent and then progressing on through the years. But I stayed on the debating team right through my undergraduate college and my postgraduate degree in Calcutta.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: I think that's an amazing story because, I mean, to my knowledge, across the world actually, there are so few schools who are teaching the art of debating. So few. And at a time where everyone is…not everyone…a growing number of people are using, you know, ChatGPT and DirectTBI to get access to knowledge, I think what the art of debating provided you, I guess, Indra, is developing your critical thinking. Because you have to not only acquire some knowledge, you've got to make sense of it, and then you've got to listen to others, understand their point of view, and then form your own point of view in return, in response to that. Which I believe is very powerful.

INDRA NOOYI: Well, that's a very, very good point. Because in those days, as you said, there was none of these tools, including no internet, no computer.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: No. Books.

INDRA NOOYI: So we had to go to the library and research topics.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Yeah.

INDRA NOOYI: And after you developed your argument, you almost had to think about, what would my opponent say and where would that person get their arguments from? And you had to research those arguments too to be able to say, how will I craft a path when it came to my rebuttal? And so I think, you know, you spend hours in the library going through material and reading, learning, digesting, drawing conclusions. In a way, today's world, everything is presented to us in a digested way. Even a speech can be presented to us now through GPT. However, even though it was tedious and arduous, I wouldn't trade that experience for anything in the world. Because it was a social experience as much as it was a discovery.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Completely. Good communication skills are so important. And Indra’s investment began early, when she was on a debate team at high school. By improving her ability to articulate her ideas clearly and persuasively, she helped fuel a rise to CEO. In leadership roles, conflicts are inevitable. Debating skills help you to meet your disputes and encourage an open dialogue, which is so essential for maintaining a productive team. Debating well also requires active listening. Leaders who can debate well are able to listen to others and respond in a way that fosters real understanding. Building up debating skills takes practice and dedication, but it can be rewarding both personally and professionally. To debate effectively, you need a broad base of knowledge first. Read newspapers, books, academic articles and reliable online sources to stay informed on a wide range of topics. Then, practice delivering your arguments with clarity and confidence. You can do this in front of a mirror. Yes, record yourself. Or speak in front of friends and family.

So let's do a fast forward on your studies. You are accepted to study at Yale, which you describe in your book as this incredibly important position in your life. And further in your book, you talk about how that feeling of being an immigrant has never really left you actually. So how much were you influenced by the idea of the American dream? And how much has that experience of being an immigrant shaped you, Indra?

INDRA NOOYI: In the seventies, which is when I came to the United States, the United States was, and still remains the shining beacon in the world. The cradle of innovation, entrepreneurship, freedom of thought, music, culture, art, you name it. The best ideas came out of the United States, and we would crave American music. When somebody sent us a cassette of American music, we listened to it over and over and over again. And one of the best kept secrets, Jean-Philippe, is that I used to play in a rock band.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Really?

INDRA NOOYI: Pretty bad rock band, but I used to play in one and we played all the American songs of that time. Creedence Clearwater and Cream and things like that.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Which instrument did you play by the way, Indra?

INDRA NOOYI: I played guitar.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Guitar, wow, okay.

INDRA NOOYI: And so you listen to this music and you say, I want to go to the place where this music was birthed. I want to go to the place where…I mean, it's so exciting, everything you hear and read. And so, when I got admission to Yale and was offered a loan and scholarship to pay my way through it, I didn't think my parents would send me, but they did. And I landed in the US thinking I would know everything about it because I'd read about it in magazines. But you land here and you realize you know nothing. I mean, it's scary. It's a big country, not as many people as there were in India, and it's lonely. I was the first in my dorm to show up that year and I was overcome with incredible loneliness. And the first two days were just overwhelmingly scary.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Horrible, yes.

INDRA NOOYI: And being a vegetarian, I couldn't find any food to eat.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Anything to eat, of course.

INDRA NOOYI: In those days. So, you know, it was challenging times, but, you know, again, you talk about incredible loneliness. I'd actually focus on the incredible generosity of people who showed up and reached out and said, "Come on, let's help you get a mailbox, a bank account.” You needed all those in those days. “Let me get you all that. Let me help you buy the right clothes to settle in." So all of a sudden, the incredible generosity and the hospitality of both Americans and foreign students really took over. And after that, there was no looking back.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: You're already talking about people who've been helping you as you land in the US. I'd love to talk about mentorship. You've credited the mentors you've had as being a great support to you throughout your life. And you found mentors, I think, in every job. The first, Norman Wade, influenced your decision whether you should go to Yale and helped persuade and soothe your parents' concerns as well. So can you tell me more about the importance of mentors? A little bit more about the role that mentors have truly played in your own life.

INDRA NOOYI: I want to separate out two kinds of people who are kind of mentors. Mentors that you pick, who can give you advice, give you suggestions on how to be a better leader, a better person, whatever. And mentors who are true supporters, promoters, who are in your line of work or line of influence so they can actually do something for you. Some people call them supporters and promoters, they call the others mentors. I've had a lot of people that chose to mentor me. I did not go to anybody and say, "Can you mentor me?"

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: They came to you.

INDRA NOOYI: They came to me. Or they were my mentors, I didn't even know that. And many of these people would give me a lot of feedback, I would respectfully listen to their feedback and improve myself. But unbeknownst to me, they also moved my future along by either suggesting me for interesting programs in India or helping me in my career. So I think that I treated every one of these people with great respect. I listened to them very, very carefully. And if I wanted to do something different from what they suggested, I always went back and told them why I was doing something different. And I always gave them credit for my success. Always, always. Even if it was a small piece of my success that I could attribute to them, I always told them that I am who I am because of the many things you taught me over my life. And I'm in touch with every living mentor even today. And generally speaking, mentors pick you, you don't pick them.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: I love that, because I’ve had a number of guests, Indra, with whom we discussed mentorship, and one particular, Melody Hopson, that you may know.

INDRA NOOYI: Of course.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Melody had this wonderful example of mentorship she had starting really her very first job out of the university. And she said the following, she said, you know, feedback is a gift and you need to look for that gift. And I think you said basically the same, you didn’t use the same words, saying, well, not only I listened to the feedback, whatever it was, because I'm sure some of the feedback maybe it was challenging, was tough as well, not always right. And the fact that you circled back to the mentors, I think is very powerful. I know for a fact, because when I see from time to time people, I didn't know I was necessarily a mentor, by the way, exactly as you said, but I've been somehow hopefully supporting, helping, developing, you know, behind the background -- coming back to me saying, “Hey, JP, at this time what you did was so important for me to achieve this and that.” And I think that circling back is very powerful as well.

INDRA NOOYI: I agree with you there. It's showing a sense of gratitude and respect for what they've done for you.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: And it's wonderful. So from the beginning, starting out at Mettur Beardsell, you experienced men dominating the room. You describe having to put up with a lot of difficult behavior, like being interrupted and talked over. You also mentioned your time studying at IIM, being taught by men and studying the work of men as well. So what effect did this have on you at the time? And throughout your career as a woman in a very male-led industry, different roles obviously, did you feel you had to change your behavior and your attitudes? And were you ever in a position where you felt you could fight gender discrimination head-on?

INDRA NOOYI: In those days, you didn't think about gender equality at all, because there were no women in the workplace. So I was just glad to have a seat at the table. And I knew I had to write a lot of the rules for behavior. And I wasn't going to write it as a woman, I was going to write it as a very good professional. So I wanted them to look at me as an equal executive who happened to be a woman as opposed to “here's a woman.” So I had a very different perspective. Because people like me, if we don't deliver as professionals, we don't set a great example for people following us. So my focus, my granular focus was on doing my job very well. That's all I focused on.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Doing your best.

INDRA NOOYI: And yeah, doing not just my best, delivering something that was valuable to the company. And very interestingly, I didn't really care about all the men surrounding me because I was doing my job. And if they ever stood in my way, I had these mentors like Norman Wade and S.R. Rao who would swoop in and make sure that I was respected or seen. So I had the hand from the back of leaders who sort of saw the value in me and pulled me up. And so I think that today is different, Jean-Philippe, because you've got more women and they're not fighting for a seat at the table like I was then. There's more of them, but they still get frustrated because progress is not as much as they would like. Although we've had significant progress, don't get me wrong, I think we have still a ways to go. And so the situation is slightly different. And the other thing too is that the more I focused on the quality of my output, the respect for me grew.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Yes.

INDRA NOOYI: And pretty soon I became just one of the guys. And more importantly, when they went off on their golfing or fishing or horseback riding weekends, they never asked me to join them. And I didn't want to be asked because I had children at home and I said, “I don't want to join you. I don't horseback, I don't fish, I don't golf. I don't eat meat, I don't drink. I have no desire to join you. I'm glad you didn't invite me.” However, however, if decisions were made in those retreats and the women were excluded, that would be a terrible, terrible commentary on the company. That didn't happen in mine.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: That did not happen to you.

INDRA NOOYI: No, I told the men, do not make decisions in these retreats because when you come back, I'm not going to do the work to support it.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Oh, wow. So you are very firm in standing up for your position.

INDRA NOOYI: Very firm.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: As an Indian woman who kickstarted her career in 1980s corporate America, Indra had to fight for years to make herself seen before famously taking the lead as PepsiCo's first female CEO in 2006. She worked harder than anyone else so that people didn't look at her as a woman, a woman of color, an immigrant. But she did not want others to go through what she had faced, so she took an active role forwarding progress. Whenever she saw biases creeping in, she would stop it.

INDRA NOOYI: You can't just, at that moment, let it go, because the senior-most person in the room has got to stop it, right then and there. The leader, if that person says, "You know what, I'll talk to him later," then what you're doing is, at the meeting, sanctioning that sort of bad behavior. So I had leaders who would stop that meeting and say, "Let her finish,” or “What's your problem? Why are you sort of smirking or rolling your eyes when she's talking?" And then when I became CEO, I'd do the same thing. Not because I was female, I was the leader. So I wanted the right behavior modeled in the room. It still didn't stop some of the men talking over the women or rolling their eyes, saying, "There she goes again." But if you called out this behavior, very soon that message went to the whole company saying, "Hey, we’d better watch it."

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Yes. I appreciate again your candor here, Indra, in the way you've been living your professionalism, number one, and certainly defend your position, I mean, through great work along your careers. So continuing a bit on your skills and some of the skills you acquired, after graduating, you went to work at BCG, Boston Consulting Group, a job which required you to learn a lot of strong analytical skills to dissect, evaluating every part of the business, of the company. I'm sure this must have been a very important job to help you to understand a business inside-out. So can you tell us more about the skill you acquired then and how that helped you, or not maybe, to progress significantly in your career? Or did you grow out of that actually?

INDRA NOOYI: Actually, I would say BCG was one of my most formative experiences through my entire life, for several reasons. One, it was very hard to get into BCG in those days, even today, but in those days it was impossible because it was considered the preeminent strategy firm. Bruce Henderson, who founded it, was like God. And you went through such a rigorous interview process. You know, it was like a lottery, winning the lottery to get into BCG. So when I got the offer, I was just, you know, it sort of gave me confidence, put it that way. So I started at BCG. What BCG did for me was, it allowed me to learn multiple industries ground up and taught me how to go in and understand the value drivers of an industry. There was no training program. We learned it on the job, but the seniors and the team taught you to do that. That was great. Second, as a young consultant, I was now interacting with C-suite professionals and CEOs. So it gave me that ability to have confidence in myself, be able to look at a CEO eye to eye and share your conclusions. It taught me how to sell in unpopular ideas, because one of the things that BCG taught us is that the client pays you for the quality of your output, not for how you play the politics. So don't try to shape your conclusions to suit the politics. Talk about what's the right answer.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Connecting that back actually, Indra, to discuss rather than debating in a way, right? So can you remember maybe one of those examples where you had to confront maybe the CEO, executive of a large company on your conclusions, your strategic recommendation for the business that they did not agree with?

INDRA NOOYI: There was a particular company where they were gung-ho in investing on a brand new technology, which would have been a different technology than all the machines that were running with the old technology. We ran the analysis again and again, and I went and studied this backwards, forwards. And I still remember late in the night at about eight o'clock or something in a small town in the Midwest, I had to tell the head of operations and R&D that we're not going to recommend investing in this new technology because it was too risky, and we might be able to leapfrog, but don't invest in a technology where you are number two, even though it's the technology used today. And I explained why that was the case, very objectively explained everything. The operations head came unglued, totally unglued, because he had banked so much on this technology coming into the company, and rightly so, he felt great ownership. And we had a few words. I mean, I kept my cool because I don't know how to utter words at them, but he didn't care that I was a female consultant across the table. He let me know exactly what he thought of me, and then he walked out in a huff. I went back to the hotel room, crushed that he was so upset.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Of course.

INDRA NOOYI: But interestingly, in a couple of days, he came around, and long after we stayed friends. Because what he did was he went back and thought about it, and he put the company before him. And he said to himself, "I think this is not about me, this is about my company."

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Which is fantastic.

INDRA NOOYI: “And if this is the right decision for the company, and the consultants have no ax to grind, they're looking at the data and the analysis and coming with a conclusion, who am I to behave so badly?" And in a day or two, he came around and it was really…for two reasons it was gratifying. One, that our conclusions were steeped in data and analysis, and he bought into it. And second, he didn't fight it. He actually came with us to the CEO to say, "I've changed my mind. I'd like to not invest in this technology." So I learned a lot about staying true to your values, staying true to the data and conclusions, having an eye towards the cultural aspects of implementing it, but base it on data. Makes a difference.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Love it, love it, and love about, again, your firmness in terms of the opinion, backed up with data evidence, and the fact that, in a way, you coached that leader.

INDRA NOOYI: Totally, yes.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: In what you just said, right? Don't put yourself ahead of the company. It's about the company's future. So let's get the facts on the table, let's decide. So, wonderful example. Thanks for sharing, Indra. So then, back in 1984, after your term as director of corporate strategy and planning at Motorola, you joined the PepsiCo team. After an instrumental role in buying Quaker Oats, you were named president. Then in 2006, you received a call informing you that you are going to be named as the next CEO. So I must ask you, that must have been an incredible moment. Can you describe the feeling you had and what you wanted to achieve as CEO in those very early days?

INDRA NOOYI: So I went from Motorola to Asea Brown Boveri, and then I was recruited out of Asea Brown Boveri into PepsiCo. And you know at PepsiCo, I just kept working away because we were making a lot of transactions between '94 and '99. Then when I became CFO, we bought Quaker Oats the first few months. So all of a sudden I was in Quaker Oats mode. And the CEO changed at that time. I was working for Steve Reinemund, the CEO, outstanding human being. And we had a great partnership. You know, we would argue, we would fight, but it was a partnership. And one day when he walked into my home when I was on staycation and told me that in a few days the board was going to name me the CEO, mine was not elation, mine was more, “God, what happens to this partnership with Steve?” It was a wonderful partnership, we were working so well together, he's still so young, why is he stepping down? Because sometimes you have partnerships where you learn a lot, where you both are working like the yin and the yang and you get into a groove. And I was actually very, very sad that Steve was stepping down. And I remember still when I told my mother a few hours before the announcement that I was going to become CEO, she goes, "No, no, you don't want to be that. Let me call Steve, he'll listen to me." I said, "Mom, that's not how it works."

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: “Don't do this call.”

INDRA NOOYI: But that was my first reaction. But then after a while, when Steve said his mind cannot be changed, he's decided this is how it's going to be. And he gave me many words of confidence in me that gave me the ability to immediately switch my brain from president and CFO to CEO, because we had a week to get all the announcements and everything ready. And so the first few days, you're just getting ready for the big announcement and how you talk to the employees, keep them all focused on the job, and then you start to think about your agenda.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: So early on you had a strong instinct that PepsiCo had to rethink its purpose in society. I recently had someone in my podcast, Ramji Gulati, who as I'm sure you're aware, has written a fantastic book, "Deep Purpose," and it references you, of course, with great admiration. It discusses the vital importance of companies of all size running their organizations with deep purpose at the core. And I really relate to that as well working for Microsoft. I believe we've got a strong purpose as a company as well, and I see the same in a few organizations in the world doing a wonderful job. And Ramji talks about purpose as essential in order to be successful in the long run, but also remain competitive with rivals, retain talent, and many more benefits. So I'm really interested in the incredible movement you created within PepsiCo that you call, I think, performance with purpose, designed to marry financial success and social responsibility, which by the way, is a big, big discussion debate of the day as well in the corporate world these days, under the name of ESG and more. So tell me more about spearheading this massive change in the company and how important it was for you to make a positive impact whilst leading PepsiCo.

INDRA NOOYI: So when I took over the company in 2006, it was coming off of years of great performance. Steve had run the company brilliantly. And when you take over as CEO, now you have to sit back and say, what are you going to do with this company? You can continue doing what he was doing, assuming that the environment will let me continue doing what he's doing, or do I need to change course a little bit? But in order to change course, I have to understand what the environment will look like over the next 10 years. So I commissioned a series of teams to look at the big mega trends that were going to impact corporations, consumer companies, food and beverage companies, and PepsiCo. So started with a broad lens and narrowed it down to PepsiCo, and said, “hey, all of you do this work, and then let's coalesce and pick the 10 mega trends we should worry about,” which we did. And of all the mega trends, three required significant investment and work, and they were very significant mega trends. The first was a move towards health and wellness. If we did not add to our portfolio more nutritious products, products low in fat, sugar, and salt, we would lose out on growth opportunities. If we didn't focus on the environment, two things would happen. If we didn't reduce water use or plastics use, either we would not get a license to operate in society or our costs would go up. So that was the second one. The third mega trend that was very obvious was many, many Gen Zers and millennials at that time wanted to work for companies with a deep sense of purpose. And they wanted to work in companies where they could be themselves at work, not necessarily act like another guy or just act like they had no families, no community to worry about. They wanted to bring their whole selves to work. So those three cannot be done overnight. I knew it needed work, but we still needed to deliver results. So performance was paramount still.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Indra’s “performance with purpose” movement has three goals. One was to drive long-term growth for PepsiCo while also considering environmental and social impact of its business practices. The second was empowering people. This involved creating a corporate culture that promoted diversity and inclusion, as well as investing in development and well-being of employees. And the third goal was to be environmentally responsible. Under Indra's leadership, PepsiCo focused on reducing its environmental footprint by implementing various sustainability initiatives. This included efforts to reduce water and energy usage, decrease greenhouse gas emissions, and develop more sustainable packaging. When she first became CEO of PepsiCo, Indra was so determined to bring about these changes that she told the board that if they did not agree with the direction she was proposing, she was prepared to leave. And if I may, Indra, it's an interesting discussion because that's back a few years ago already. You are sitting, of course, on a number of boards today. How do you see those discussions evolving at the board level? Is it significant and is it significant enough? I'm not asking for any names of company again, but the way you feel it, and if you are in the shoes of the CEO yourself, on the other side of the table, would you, and do you actually push back in some cases to ask for more or differently? What is your assessment of the evolution of the corporate world when it comes to that deep societal impact embedded into the business fabrics?

INDRA NOOYI: That's a great question. I would say that if you looked at every corporation today, what you cannot afford to do is create an ESG department that's so metrics driven.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Silo as well.

INDRA NOOYI: That is not linked to the business.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Yes.

INDRA NOOYI: And it does not create value. You've got to think about those ESG metrics, which, you know, ESG is a very sensible framework, but think about those metrics that are intricately tied to the businesses.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Right.

INDRA NOOYI: And performance and value creation. And don't call them ESG, just talk about it like we did.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Yeah.

INDRA NOOYI: It's performance with purpose, but we cannot deliver performance without a focus on the three purpose planks.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Yeah.

INDRA NOOYI: We cannot focus on the three purpose planks unless we deliver performance. So it was a virtuous circle. And I think if you reframe it and restate it as inherently linked to shareholder value creation, which I think it is. I think it'll land better with some of the people who are going to find fault with everything you do anyway.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: For sure.

But I think in this case, we may have created a problem. Companies, society may have created a problem by segregating ESG as a big metrics exercise. Companies created ESG departments and said, "Keep me out of trouble,” and focus on too many metrics. Focus on the vital few, link it to shareholder value.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: I love that. I'm a hundred percent with you, Indra, and the fact that you need to really embed into the core core again of fabrics of what makes your company so unique and special. And to bring the best of that fabrics actually entails positive impact to the planet and the people. And then pick, pick, pick, pick, pick your bets. Pick the places where you can really make a big difference because of your scale, your system and so on and so forth. So let's go back to that. In particular as well, relationship between some of those big enterprise strategies, you know, when it comes to the bets you made at the time PepsiCo and the personal relationship you may have with that. I think that one of the huge focus was in your case to put in place strategies for lower water consumption, which happens to be actually an even much harder, more challenging and terrible challenge for the world today. You also did better packaging solution, reducing of course companies' carbon footprint. But coming back to water, I understand the community in which you grew up was, I understand, subject actually to water rationing daily, right? So to what extent did this become personal for you, maybe?

INDRA NOOYI: Oh wow, 100%.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: In terms of the connection to water, reusing water, consuming water.

INDRA NOOYI: Let's stay with water. There were other things too, but let's stay with water. Typically on all of these purpose issues, if you feel it deep down in your heart, you will make the change. If it's purely an intellectual exercise, you find a way not to make the change. Okay? In my case, and in the case of many people who grew up in water distressed areas, whether it was in Mexico, whether it was in parts of Africa, or parts of South Asia, wherever, where there are many, many, many water distressed communities to have a big city struggle to have water for day-to-day eating or drinking. But a manufacturing plant on the outskirts of the city, using two and a half liters of water to make a liter of a beverage that's fun for you, is not a very good equation. It's not good for the company, it's not good for the society. And when water levels started to deplete, corporations used to take their resources, build higher pressure pumps, and draw water from the aquifers. I would argue that that's a bad outcome, because one day you will get shut down by the local community, which was happening in many parts of the world. So from my perspective, I felt it deep down inside. Nobody needed to tell me we needed to reduce water because I felt it deep down inside. So I told my R&D people, we're going to get it down to 1.2 or 1.3. Let's figure out a way to reconceptualize how we use water in the plant. And you'll be amazed, if you put the best people against a problem, they will find a solution.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: For sure.

INDRA NOOYI: And that's what we did.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: If you give them permission to do it.

INDRA NOOYI: Totally. You know, liberate them and give them the tools and investment, they will find the solution and they did.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Yeah, so continue a bit this discussion, Indra. I'd like to talk about the way you engage people, employees, in such a challenge. You know, I had a great dialogue as well in one episode with Paul Polman, which I'm sure you know. And of course, the way he shaped the famous Unilever or sustainability living plan, right, for 10 years and the way he engaged in all of the change. He often talked about it that the starting point was like, having every employee going through this workshop about personal mission. Why? Why they do what they do in terms of their work, their daily lives with their family and so on and so forth. So love to go back to your experience as well as the CEO of PepsiCo at the time. What did you do to engage not only your executives, of course, and I understand you've been writing letters, actually personal letters on performance with purpose, but to the entire employees, right, workforce, to engage them meaningfully in the way they could have an impact on that purpose with the performance.

INDRA NOOYI: To me, big transformational programs like the one we were embarked on require you to have missionary zeal yourself as a CEO. You've got to get the message out, you've got to be visible, whether it's by video, whether it's in person, you've got to be the missionary. And this goes back to communication skills developed early in your life. You've got to go out there to every country, frame performance of purpose in the context of that country. Don't talk to them about water shortage in India. You know, if you're in, you know, Bangkok, talk about why performance with purpose is relevant to Thailand. Explain why performance with purpose was relevant to Mexico City in Mexico. So you've got to tailor that message for every country, every community you're going to speak in, with examples that touch their hearts. And so every time I was out there talking about performance with purpose, I would tailor the message. I would start broadly, but very quickly tailor the message to them so that they got it in their hearts. And very often, I didn't have to continue, they would pick up where I left off and talk about why this was going to be so wonderful for their communities, for their country, and why this is something we should embrace. So very often, I didn't have to convince them; they were convincing themselves and their people as to why this was the right thing to do. So I give credit to a lot of the PepsiCo employees.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: That's great. But were you also able to have more of like a bottom-up approach where, because of that local context you are allowing and empowering the people on the front line, right? To basically drive and maybe come up with local initiatives to make a difference with water consumption, with plastic usage, whatever.

INDRA NOOYI: Totally.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: I mean, the biggest challenges you have to face in every country in the world.

INDRA NOOYI: I think PWP touched their hearts. So every one of them was coming up with ideas for how to take out quarter of a gallon of water, half a gallon of water, or recycle plastic a little bit more. Everybody thought this was their initiative because they'd go home and talk about it proudly with their family and their kids, about how PepsiCo is going in a direction that should make all of us feel proud of the company. You've got to evoke that pride.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: I would like to pick up on this point briefly. Generating pride among employees for the work they do is a key element of positive leadership. And Indra was brilliant at setting a strong example, clearly articulating PepsiCo's mission, vision, and values. When employees understand the purpose and direction of the organization, they are much more likely to feel connected and proud to be part of it. And in Indra's career, she's never been afraid to take risks for the greater good. In 2009, she set up the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, which brought together 16 of the leading food and beverage companies committed to cutting calories in the products they sell.

INDRA NOOYI: We committed to removing 1.5 trillion calories from the American diet in 5 years.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: I don't even…I can't even imagine what it is compared to the base, by the way. It looks huge.

INDRA NOOYI: I think it was 10% of the base that had to come down. Significant.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Okay, significant.

INDRA NOOYI: We actually took out 4.5 trillion calories in 3 years.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Wow, wow.

INDRA NOOYI: And close to 5 plus trillion calories in 5 years. So the industry did a phenomenal job reformulating, you know, taking out excess calories and salt. And all goes to show when you put good people in a room and tell them, "We're going to do something that's right,” people step up.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: But do you think it's enough today, actually, Indra? Is it something that should continue in a different way?

INDRA NOOYI: It's a journey. It's a journey. I think what needs to happen is, you know, more better for you and good for you choices need to bubble up. But ultimately, it's a consumer pull. You can put every nutritious product on the shelf, but if the consumer says, "I want the fun for your product," you cannot force the consumer to go another way. My only plea to the industry is, don't make the healthy choice the expensive choice. Don't make the healthy choice a bad tasting choice. And don't make the healthy choice an unavailable choice. Make it equally available, affordable, and great tasting.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: I think that's a great summary. I think of one of the biggest challenges today of bio products as well.

INDRA NOOYI: Right.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Bio organic. Anyway, so let me shift gears now and come back to an earlier discussion we had a bit, because I want to get a bit deeper on diversity and inclusion again. Because I think it remains a very important topic globally, by the way, not just in the corporate world. You know, I recently had a former CEO of Netflix, Bozoma St. John, that you may know maybe, on the podcast, I'm sure you know her actually, for good reason. She has a great way of explaining the difference between diversity and inclusion. She said, "Diversity is about being invited to a party, "and inclusion is being asked to dance." As you rightly say, it's not enough to just have one diversity and inclusion officer, just like for the ESG officer. It doesn't solve the problem. You know, diversity and inclusion has to be in the CEO's mandate, of course, the executive, the board as well, and a subject of boardroom discussion. So it takes the whole leadership team to really be on the same page, and more importantly, to hold them accountable. So can you talk to me about how you carried the torch as CEO of PepsiCo, and your advice for other companies, particularly the ones you are certainly at the board of, on what's more, and what's different that they should do to change the course of diversity and inclusion?

INDRA NOOYI: Again, this is where I learned a lot from Steve Reinemund, my predecessor. He set the tone for how we should think about diversity and inclusion. He said, "We are a consumer products company. Our employee base should reflect the consumer base for us to make the right decisions." So he said, "We're not there, and we need to get there first." Second, he said, "You cannot have inclusion and equity without diversity." He said, "There's no point having one person and everybody practice inclusion with one person." So he said, "Step one, we're going to get a critical mass of diverse people in. And then we're going to learn to make them feel included. That'll lead to equity." So let's be very clear, that's the journey.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: The steps, yep.

INDRA NOOYI: Yes, and so he first implemented a scorecard on how to get diverse people in, because he said, "They exist out there, we just don't look for them. And when we do look for them, we reject them very quickly." And when he put that in, it was amazing how many qualified people joined the company who were diverse. Then the next step is, how do you teach people the skills to make others feel included? Because people are behaving the way they've always been taught to behave. And all of a sudden, somebody's telling them that's not good inclusive behavior. And that creates its own dissonance. And so we actually had a training program, levels of inclusion training, just to treat people, everybody who's working with us, as the same. And you would think it's so basic and simple, but it's not. And so Steve put that training in place and that gave me a lot of tailwinds because I could now build on what Steve had started already in the company. And we already had a critical mass of leaders. They could now spread the message on the fact that PepsiCo was a very open place and welcoming of talent as long as it's contributing to the company, it doesn't matter what your background or ethnicity or your gender was, we want you in the company. And so that message got out very quickly and everybody wanted to join the company.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Do you have any views actually, again, as you sit at the board of a number of companies, Indra, on executive compensation related to diversity and inclusion? Does it matter? Does it change behaviors all across the leaders and the managers? Because we all know, from the top, you know, it's important, but sometimes you've got five, six layers of management or more in some large organizations, and it doesn't necessarily flow through. So what is your view on that to get that systemic change all across a large organization?

INDRA NOOYI: So in the past, in PepsiCo, in our annual performance appraisals, 70% of the bonus pool was on business results, 30% on people results. We changed it to 50/50. I mean, you change it to 50/50, the few people-related issues, everybody paid attention to succession, people development, diversity and inclusion, people pay a lot of attention to that. So every time we tried to make it three simple measurable metrics on the business side and the people side, and we changed to 50/50 and put simple metrics, one of which was on diversity and inclusion, one of which was on succession development etcetera. Employees…managers paid particular attention to it.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: It's really brave because I'm not aware, and I don't know, of course, all the exact compensation plans, what the plan is, but I've hardly heard about large companies putting 50% of their compensation plans on --

INDRA NOOYI: Annual bonus.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Exactly, on people. It's pretty rare. So really a great move, I think, personally, and a wonderful move to change behaviors and get attention and make a systemic change.

When Indra took on the job of CEO at PepsiCo, it was intense for the whole family, for herself, her husband, and her two kids. Indra admits to having leaves at the company while working there. The all-consuming nature of the job almost required that level of commitment. Her family knew life was going to change and that Indra was going to become a very public figure. I wanted to understand more about how Indra felt about those challenges and trade-offs, and how she dealt with her family being in that tough job?

INDRA NOOYI: You know, the undisputable truth is that there's only 24 hours in a day. And the truth is that when you're a CEO or a C-suite executive, your job takes a disproportionately large percentage of your time. And when you have a family, that's a full-time job. Being a mom is a full-time job. Being a wife is a full-time job. So all of these take time. And you can't stretch the day too much unless you're superhuman, which is you can multiplex, you can get by with little sleep, you can do three things at the same time by worrying about your kids, your job. Somehow you can do all that. The reason I don't like the word balance, Jean-Philippe, is because that implies that you can tell your kids, "If you have any problem, you can only call me from 9 to 9.30 in the morning." Or, "If you're really sick, you can only call me from 3:30 to 4:00 because I've slotted you in." That's not how life works. They can call any time. A crisis at work can show up any time. You are constantly juggling your priorities. I don't know what I would have done had I had a sick parent or a sick child who required a lot of attention. I am in great awe and admiration for people who are trying to manage all of that. It's a big challenge. I was able to do what I needed to do because I didn't have those sorts of issues so I could focus on the job and somehow keep a family life going. But I will tell you, especially as a woman, I went through a lot of guilt many times. I'm not giving them the time, or I'm preoccupied, is this the right thing to do? But at the same time, people don't realize that, and I would say CEO and CEO-minus-three, those positions, once you get to that job, it's up or out. Because there are people always pushing from the bottom for your job. So for you to keep that job, for you to keep your job is a big thing. You have to constantly learn, you've got to stay one step ahead of everybody else. So it's up or out. So the pressure actually goes up as you move up that pyramid. And you can imagine how it was.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: For sure, for sure. It's great that you actually opened up in that real life, I mean, that you’ve gone through, Indra, and again, recall of us that each one of us has a different context as well. And it's super important we don't generalize when we talk about that as well.

INDRA NOOYI: That’s exactly right.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: I think that can be very confusing. So last couple of questions. Since retiring, you've been actually extremely busy, maybe even more than as CEO, I don't know, differently, I'm sure. One focus for you is to help build up the care system to support young people, actually juggle family life and career in order to help advance women in the workplace. So can you tell us about your mission to help and your ideas for how the government and private enterprise could help in that context?

INDRA NOOYI: The fact of the matter is we need women in the workforce because the women are doing exceedingly well in colleges, they're getting more degrees than the men, they're hungry, they want economic freedom. And if our country is going to succeed because of the quality of the talent, we’d better put to work everybody who's got talent, and that includes a lot of men, I mean women too. At the same time, we also need children. We can't afford to have the birth rate fall too much. And so the only way to thread a needle between these two is to say we want women to be family builders also, we want you in the workplace, so we have to provide an ecosystem around men and women, young family builders, not just to contribute in the workplace, but also contribute to building societies. So we're going to give you paid leave when you need it, we're going to give you child care support. Now with post-Covid, we can give you flexible working time. So we have to make the three legs of the stool happen, because if we don't, one of two things will happen -- women will drop out of the workforce because it's just overwhelming and too stressful, which we don't like, or they will put off having children, which we don't like. So I don't think it's a “nice to do,” it's a societal impeditor for the country. So we have to solve for childcare and eldercare and figure out how to implement sensible paid leave. I'm not just saying give paid leave ad infinitum to people. How do you do sensible paid leave where it makes sense for companies too?

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: Those are great advices and I'm sure…and of course the situation varies a lot, you know, one country at a time across the world, depending on the care system put in place or not, by public sector, but also by private sector as well. My very last question, Indra, what's next for you? And what are your three coaching recommendations for the next generation of leaders today?

INDRA NOOYI: You know, you don't implement performance with purpose in your career and then walk away from purpose. So my post-retirement life has been a lot about purpose, giving back, mentoring, doing a lot of teaching. So it's been a very productive experience that way. Let me turn to what leaders have to focus on today. I've never seen the world change in such profound ways as it is today. Technology is not just developing. There are technology tsunamis almost. It's going to reframe the way everything is going to get done. And so every leader or every aspiring leader has to commit themselves to lifelong learning. There is no way out of it. Because if you don't stay current and learn everything, you're going to be left behind and it's going to be a challenge. The second is, we all have to think very, very hard of not just outputs, but also outcomes. Example: we've been talking about ChatGPT and what it's going to do for productivity and how it's going to make back offices more efficient, medical areas better. Nobody is really talking about the mass reskilling that has to be done in society. So we've talked about outputs. We haven't talked about outcomes. What are we going to do with people? How are we going to reskill? What are the people who are going to be left behind from these technological innovations, how are they going to be re-potted? We don't talk about that at all. And the third, I think we have to be prepared for a world where a lot of the changes are just going to happen on their own. For example, climate change. It's going to happen. Whether we do anything or not, it's going to happen. The geopolitical conflicts are going to happen anyway, we can't stop it. So we have to accept a certain degree of events that are going to happen. But whatever we do, we can slow it down, but it's going to happen. And then focus on what we can do to slow it down or operate within that. For example, we went from the world is flat to now retreating to national borders. Rather than lament it, we now have to be pragmatic and say, what is the new business model? What are the new supply chains? How do I now become a multiple domiciled company as opposed to thinking about the world as flat? So I just think you've got to accept some of these as inevitable and plan for the worst and deliver the best. And so it's a different mindset.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: I love Indra's conclusion there. She's got such a distinctive leadership mindset. And I draw a lot of wisdom from her long-term vision and the importance she puts on resilience and adaptability to help us navigate through the challenges ahead. Thank you so much for such an inspiring and insightful dialogue. I'm sure all of the listeners will love it. So thanks so much.

INDRA NOOYI: A pleasure Jean-Philippe, it was a real pleasure chatting with you.

JEAN-PHILIPPE COURTOIS: From her humble beginnings in India to her rise as one of the most powerful women in the world, Indra's life journey is a testament to her grit, determination and hard work. Yes, she was fortunate to have a supportive, tight-knit family. But to get there and to stay there required lots of trade-offs, lots of sacrifices. Her story acts as a reminder of the importance of making an impact and delivering purpose, and of how delivering purpose starts with being willing to understand all parts of the business. In today's world, leaders need to have an insatiable curiosity. If you don't, you won't move ahead. As a leader, as a person, Indra is someone who understands her power and delivers her truth. In doing so, she sets an incredible example. Remember, when you are trying to find alignment between moral and financial success, communicate authentically, speak honestly and openly. Never be afraid to give your own point of view. You've been listening to Positive Leadership with me, Jean-Philippe Courtois. If you enjoyed this episode, why not leave us a comment and rating and share it with your friends. And if you'd like more tips on driving personal growth, leadership excellence and positive change, head over to my LinkedIn page and subscribe to my monthly newsletter, Positive Leadership and You. Until the next episode, goodbye!