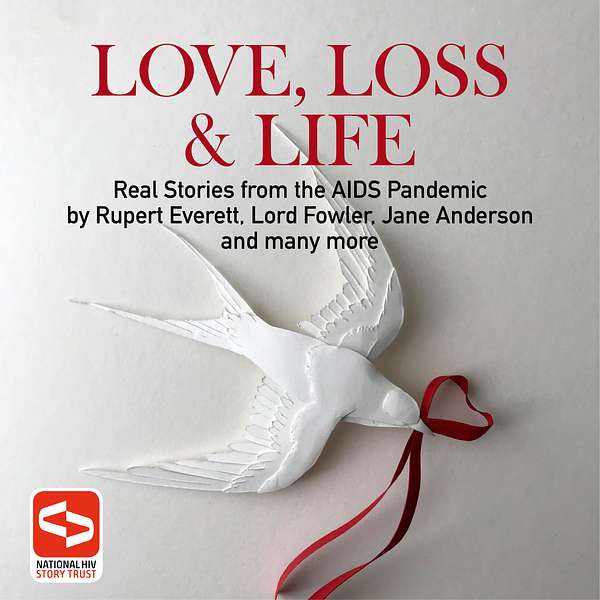

Love, Loss & Life: Real Stories From The AIDS Pandemic

Introduced by Anita Dobson and voiced by actors Christopher Ashman, Elexi Walker, and Kay Eluvian, the series features stories taken from NHST’s first book, a collection of essays, reflections, and testimonies also entitled ‘Love, Loss & Life’ which was published in 2021. The book and podcast series feature in short-form just some of the moving and tragic recollections that the NHST archive of over 100 filmed interviews, currently housed at the London Metropolitan Archive, capture in expansive detail. This extensive archive provides a 360-degree thought-provoking view of the AIDS pandemic in Britain through the real-life experiences of those who were there. Since 2015, over 120 interviews have been filmed with survivors, family members, friends, advocates, and medical professionals candidly remembering their personal experiences. Through archiving these films at the LMA, and sharing the stories collected through education, media, and art projects, NHST’s mission is to preserve the story the HIV and AIDS pandemic for those who know it, and to teach it for the first time to those who do not.

Love, Loss & Life: Real Stories From The AIDS Pandemic

Love, Loss & Life: Real Stories from the AIDS Pandemic: Lord Fowler

Your feedback means a great deal to us. Please text us your thoughts by clicking on this link.

As Minister of Health in the mid-1980s, Lord Fowler found himself at odds with Margaret Thatcher and other members of the Cabinet over how much attention should be paid to the AIDS pandemic. Some neat political manoeuvring enabled him to run a memorable public health campaign which made the nation aware that HIV and AIDS could affect anyone.

This podcast series features stories taken from our first book, a collection of essays, reflections, and testimonies also entitled ‘Love, Loss & Life’ which you can buy here.

An audiobook is also available here.

Visit the National HIV Story Trust website

'Love Loss and Life' - Real Stories from the AIDS pandemic. This is Lord Fowler's story read by Christopher Ashman with an introduction by Anita Dobson.

Anita Dobson:After a career in journalism, Norman Fowler was elected as a Conservative Member of Parliament in 1970. He served in Margaret Thatcher's government in the 1980s, first as Minister of Transport, and then as Secretary of State for Health and Social Security, remaining in that post from 1981 to 1987, and overseeing the government's response to HIV and AIDS, including the memorable advertising campaign to raise awareness in 1987. He then became Employment Secretary but resigned from the cabinet in 1990. He was knighted in the same year. Later, he returned to frontline politics as Chairman of the Conservative Party from 1992 to 94, then sat on the Conservative front bench from 1997 to 1999 as a member of the Shadow Cabinet, finally stepping down as an MP in 2001. He became a Conservative life peer Baron Fowler of Sutton Coldfield, and entered the House of Lords. Renouncing party political allegiance, he became Lord Speaker in 2016, a post he held until April 2021. He continues to campaign for LGBT rights and to raise awareness of HIV and AIDS as a UN AIDS ambassador, and is a patron of the Terrence Higgins Trust. As Minister of Health in the mid 1980s, Lord Fowler found himself at odds with Margaret Thatcher and other members of the cabinet, over how much attention should be paid to the AIDS pandemic. Some neat political manoeuvring enabled him to run a memorable public health campaign, which made the nation aware that HIV and AIDS could affect anyone.

Lord Fowler (read by Christopher Ashman):When the question of how to deal with AIDS in the UK arose in the mid 1980s, it seemed to me there were very few policy options. We could have ignored it, and there were plenty of people in government saying just that. I had little connection with either the LGBT community or drug users, among whom the disease was spreading fastest, but I could not understand the arguments of those who said it was nothing to do with us. As Health Secretary, I felt we had a duty to get the message out to as many people as possible, that this was a terrible condition, and a public health issue. There was no vaccine and there was no cure. The man who did most to bring it home to me was Donald Acheson, who was the Chief Medical Officer. If Donald said this was a serious issue and likely to worsen, you could be sure he was right. He predicted that if infection rates continued to rise, within a couple of years there would be 20,000 people with HIV in the UK - which then meant 20,000 deaths. There were some who believed this was not a public health issue, but one of public morality. The Chief Rabbi was one of the most vociferous, telling me my policy should be to say plainly that AIDS was the consequence of sexual deviation, marital infidelity, social irresponsibility, and a generation who put pleasure before duty and discipline. Frankly, my view was that if a government is so foolish as to run a moral campaign, the first time a Minister is caught with their pants down or putting cocaine up their nose, the whole campaign goes up in smoke. I was proved right, a few years later, when John major's 'Back to Basics' campaign, an appeal for a return to traditional values was ridiculed after a series of scandals involving Conservative politicians. Our only weapon to fight the disease was publicity, and I was determined to get a strong campaign going. "Don't die of ignorance" - with a leaflet sent to every household in the country. But Margaret Thatcher, though she showed a good appreciation of the science when I took Donald Acheson to brief her, was convinced I was becoming obsessed. "Norman", she said, "you mustn't just be known as the Minister for AIDS". I thought for a moment, that might mean I would next be promoted to Chancellor of the Exchequer, but no such luck. The subtext was, Norman, you're spending far too much time on this subject, kindly go and do something else. Though she might not have put it in quite the same terms as the Chief Rabbi. Her view was, in some respects, very similar. If we gave out explicit information about what kinds of sexual activity were risky, we could expose young people to the shock of knowing things they would be much better off not knowing. The way I always handled Margaret was that if there was likely to be a point of conflict, it was safest to go round her rather than through her. I had a number of opponents in the Cabinet as a whole, so getting agreement on anything was time-consuming and difficult. Lord Hailsham, a grand old man of politics criticised me for the phrase'having sex' in one of our advertisements. "Quite inappropriate", he huffed. "Is there no limit to vulgarity"? Robert Armstrong, the Cabinet Secretary, Ken Stowe , my Permanent Secretary in the DHSS, and Donald Acheson hatched a plan with me to set up a separate committee within Cabinet to hammer out policy for AIDS and HIV. To my great relief, the efficient and broadly sympathetic William Whitelaw was appointed to chair it. I'd recently had an exhausting experience trying to get policy through a Cabinet Committee on Social Security with Margaret in the chair. We managed to ensure neither Lord Hailsham nor Norman Tebbit, another fierce opponent of AIDS policy, were on the committee. The leaflet was quickly endorsed by the committee, as were most of the proposals we discussed, though by no means all. Donald was an advocate of practical health initiatives. His great-grandfather was a medical man at the time of the First World War. There was a terrible problem of venereal disease among the troops. A campaign was run, 'Think of Queen and Country'. Hardly surprisingly, it had little effect. Only when someone had the bright idea of issuing the troops with the forerunner to condoms did the incidence of VD begin to fall. It was a lovely example of practical public health policy, and we wanted to try something similar to combat high rates of HIV among injecting drug users by distributing clean needles to addicts. But though I had the backing of almost every independent committee that looked at the issue, I ran into serious opposition. The view was that giving out free needles effectively condoned crime, whereas I felt that was hardly the issue. We should not leave drug users to continue sharing dirty needles. After a great deal of argument, it was approved, but I am convinced that if William Whitelaw had put it to a vote, instead of simply summing up in our favour, we might well have lost. The advertising campaign attracted a lot of criticism. It was accused of being overdramatic with its tombstones and icebergs, and John Hurt's marvellous voiceover. But I make no apologies. We had tried discreet little paragraphs in the newspapers to absolutely no effect whatsoever. If we were to have any impact at all, we needed to wake people up. Fortunately, the committee agreed. We put up posters, we ran television and cinema commercials, aiming for language that was both forceful and scientifically accurate. Later, we did a follow up poll, and over 90% of the public agreed with the way it was done. To be honest, I am not used as a politician to getting 90% support, so it felt like a vindication. The infection rate of HIV went down, and interestingly, so did the incidence of other sexually transmitted diseases.

Christopher Ashman:In 1987, I flew to the United States to see if there was anything we could learn from them. But the Federal Government was doing very little, leaving it to State administrations who weren't doing much either. Any progress was achieved by activists in the gay community. I visited a hospital in San Francisco and was photographed shaking hands with a young man who had AIDS. This was some months before Princess Diana created a far greater stir by doing the same. When I returned Margaret Thatcher and Norman Tebbit, the Party Chairman, were outraged a British Minister had been photographed meeting as they thought unsavoury characters. I suspect my successor at the Health Ministry, John Moore was told in no uncertain terms he should concentrate on other matters and not follow in my footsteps.

Lord Fowler (read by Christopher Ashman):A senior Cabinet Minister said to me not so long ago, "Well, no one dies from AIDS anymore". That shows the lack of understanding among even intelligent people. Globally, we have now lost 36 million people to AIDS, according to UN AIDS. I am somewhat sympathetic to people who knock down statues of slave owners, because I think we should take a lesson from it and ask ourselves what future generations might say about us too? Will they ask why we allowed 36 million to die? Couldn't we have done something to prevent it? And of course, we could. We could stand up against the prejudice against gay people and the stigma of HIV worldwide, especially in some parts of Africa, and certain countries in Eastern Europe. We could do more for the families of those who die and those who suffer an impoverished old age. By far, the most persuasive factor in removing stigma and the wall of silence that allows infections to go on rising is for people to come out and say they are HIV positive, telling us what it has been like for them. These stories need to be told, because it is all too easy to forget. I would hope that people in future will be able to learn from them and make better decisions as a result.

Christopher Ashman:Thank you for listening to this story from'Love, Loss & Life', a collection of stories reflecting on 40 years of the AIDS pandemic in the 80s and 90s. To find out more about the National HIV Story Trust, visit nhst.org.uk. The moral rights of the author has been asserted. Text copyright NHST 2021. Production copyright NHST 2022.