The Heart Gallery Podcast

The Heart Gallery Podcast brings you artists and creators that confront the issues of our time, help us create deeper relationships with other inhabitants of this planetary home, & inspire compelling visions of the future. Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer is the creator and host of The Heart Gallery Podcast. She is an illustrator and creative education strategist, and works primarily with humanitarian, climate, and social change organizations. She also has a studio art practice where she applies lessons from her podcast guests and her surroundings.

The Heart Gallery Podcast

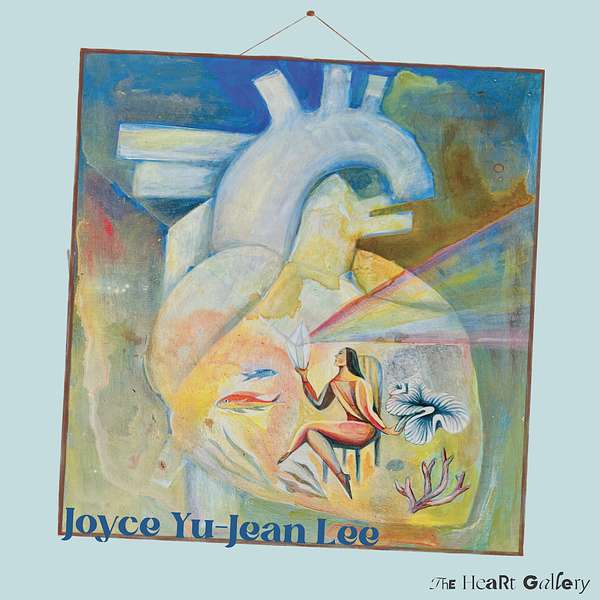

Joyce Yu-Jean Lee on understanding of the “other”, mesophotic corals, & the responsibilities of an artist

For Episode 3 of The Heart Gallery Podcast, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer talks to artist Joyce Yu-Jean Lee. Joyce works with video, digital photography, and interactive installation that combine social practice with institutional critique. Curious about how the act of seeing is transformed by technology, her artwork examines how mass media and visual culture shape notions of truth and understanding of the “other.” Listen to hear from the incredible Joyce Yu-Jean Lee.

Visit The Heart Gallery's visual accompaniment for this podcast episode here (podcast transcript also available here).

HW from Joyce: “Next time you're in a debate with a friend or a family member about an issue, really pause and think about the perspective of the other. Before you add your answer or your own perspective just pause and really reflect on what that other person is thinking or feeling. See if you might put yourself in their shoes. Try to empathize with their point of view before you speak.”

Mentioned:

- James Turrell

- Pipilotti Rist

- Ai Weiwei.

Connect:

- Joyce IG

- The Heart Gallery Instagram

- The Heart Gallery website

- Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer Instagram

Credits:

Samuel Cunningham for podcast editing, Cosmo Sheldrake for use of his song Pelicans We, podcast art by me, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer.

Note: Transcripts are generated in collaboration with Youtube video captioning and ChatGP3 and are not extensively edited.

[Music]

Hello and welcome back to the Heart gallery podcast, with me, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer. I am an artist, creative advisor, and visual communicator in the climate and humanitarian space where I’ve worked for over decade, and I also have a personal art practice where I explore relationships between individuals, other living beings, and our earth.

I created this podcast to inquire into the various roles that art can play in helping us create deeper connections with our surroundings and others - both human and more-than-human. Listen to hear from other artists engaging in these interrelationships with all kinds of approaches, philosophies, and hopes for the future of humanity and our planet, and learn about different ways that art can help create change.

In this episode I talk to visual artist Joyce Yu-Jean Lee. Joyce works with video, digital photography, and interactive installation that combine social practice with institutional critique. Curious about how the act of seeing is transformed by technology, her artwork examines how mass media and visual culture shape notions of truth and understanding of the “other.” Her project about Internet censorship, FIREWALL, garnered backlash from Chinese state authorities in 2016 and she has exhibited at Lincoln Center in New York City, the Oslo Freedom Forum in Norway, the Hong Kong Center for Community Cultural Development – Green Wave Art, and the Austrian Association of Women Artists (VBKÖ) in Vienna. Joyce’s artwork has been written about in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Hong Kong Free Press, China Digital Times, Apple Daily Taiwan, Huffington Post, and many others. She is an Assistant Professor of Art & Digital Media at Marist College and previously taught at Fashion Institute of Technology, Maryland Institute College of Art, Corcoran College of Art + Design, New Jersey City University and worked at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

I became aware of Joyce and her work when I heard her speak at an art show opening here in Washington DC. I was captivated by her work illuminating recent scientific discoveries in the mesophotic zone, the little known ‘twilight zone’ of coral reefs that is deeper, colder, and harder to study than reefs closer to the surface. We talk about that work in this episode, in addition to discussing how art can be used to connect with “the other”, reconciling social commentary art work with the elite settings it is often found in, and how to navigate artwork generating potentially dangerous attention. I found what she said about the agency of the consumer to be of critical value, and also what she shared with me about whether or not artists have responsibility to be of service to society.

I’m so grateful to have gotten to have had this conversation with Joyce Yu-Jean Lee.

[Music]

R: Hello and welcome to The Heart Gallery podcast.

J: It's so nice to have you here. Thank you for having me, Rebeka.

R: I wanted to start by examining your background a little bit if you're okay with you. I read a couple articles and I saw that you at one point were on the verge of going into fashion… You were a college student at UPenn, I believe, and you had an internship in New York City for the summer at a fashion house and you are also at the same time interning or assisting a Japanese-American artist also in Manhattan, Makoto Fujimura. It seems like you were living these two lives together, and then you went back to school and 9-11 happened. I read an account from you where you were sharing how this was a moment of reckoning for you about your career, about what you wanted to do, what you wanted to spend your time on. Can you share more about how that was a milestone moment in your life?

J: Yeah so 9-11 was a really big game changer for me. I knew many people in it. The guy I was dating at the time, my college boyfriend, was working at World Trade 7 and I had cousins that were in various buildings in the financial district. One of our classmates from college, his father worked in Tower 1, his father's name is Alex Chang and so when 9-11 happened I was on the college campus and actually was in a painting class taught by Susannah Jacobson who's a professor from Yale and she came in and she just said, “an airplane flew into the Pentagon”, and I remember our class was kind of stunned, but we did have one student whose brother worked in the Pentagon and she started crying. We were just dismissed and it took a while for me to really realize the gravity of what had happened that day so I just went to check my email and um I got a bunch of emails from friends assuring me that my boyfriend was okay and it dawned on me like oh I know a lot of people who worked down there and so unfortunately in the two weeks afterwards there was a lot of tracking family and friends and figuring out where they were and realizing that unfortunately um our classmate John his his father had passed and so that experience at the start of my senior year in college back to back with having just spent the summer in New York City doing these internships that you referenced was really a paradigm shift for me.

I was also not in love with the fashion industry after I got a closer glimpse at it and working with Makoto really opened my eyes to the day-to-day life of an artist, and I realized well if if I could wake up tomorrow and it's my last day (because we live in a crazy world and who knows what kind of attacks might happen or environmental catastrophes like we're seeing now this year) if I can wake up tomorrow and it's my last day I want to make sure that when I pass I'm doing something I really believe in.

Even though I had been studying Communications at University of Pennsylvania and I thought it was a good compromise between kind of this practical get a job track and blending the creative, it didn't really give me life and so I realized at that point I've always loved art. When I was a child I was voted most likely to become an artist in high school. I did all these art competitions and things and so I just realized that I think I have to do something I truly love and every day would wake up feeling good doing and that's art.

I didn't even have a plan but I just knew that I would have to turn my track around.

R: Did it take you that long because you felt like art wasn't a viable track?

J: Yeah, because you know I grew up with Chinese Taiwanese American immigrants so they're very cross-cultural transnational and this stereotype of the Tiger Mom held true in our family to a certain degree. My parents always said you can do anything you want for your future vocation but my mom insisted you have to be in the top 20 percent.

R: I love that, “whatever you are be a good one”

J: Yeah, so I remember as a child is really challenging that you know I asked her well what if I wanted to be a garbage collector - and I think I probably was like in second or third grade at this point - and my mother said garbage collectors in Texas make more than public school teachers so yes you can be a garbage collector as long as you're the top 20%. You have to work really hard you know in whatever it is that you choose so I think that was the thing that kind of prevented me from considering art as a viable livelihood like. I had no example in my community growing up in Texas in my Chinese American community of what an artist's life looked like which is why meeting Makoto who's um you know Japanese American was really an eye-opening experience.

So I then realize this is what artists do with their day-to-day, and it is possible. And after 9-11 it just it really drove home like to me what I'm most passionate about and what I wanted.

R: Was that scary, did you in that moment think back to your mom's advice and think like oh gosh now I have to figure out how to be in the top 20 % if I'm going to be an artist?

J: I wasn't thinking about the top 20 % at that at that point I was really thinking about you know I was thinking about my classmate John and what it was like for him to have a dad one day and then not. And I thought to myself like everybody's time on this Earth is is precious and limited and so it's really focusing on how I wanted to spend that time for myself.

R: And you haven't looked back since is that right?

J: I haven't looked back. It's been a hard journey but a really worthy one and no it sounds kind of cliche to say but I am very happy focusing on making work.

R: That's fantastic and and it seems to me from my research your body of work since that time has just been… I mean it's just so impressive and I just want to share a couple of your projects just to illustrate the range of topics you've been working on. Just to give the audience a sense of of what it is that you have been doing I'm going to choose a couple projects that come to my mind: there is this one that you worked on around the 2016 election uh where you spent 28 days praying and I think you called this a “gesture of empathy” to Muslim Americans. You did this incredible thing where you were tracing your hands and your legs, or knees, on paper and then you created these incredible patterns that then became a site specific installation. Then another project (which is actually how I came to know of you), you recently were working on raising awareness about Mesophotic Zone corals. You can share more about it, but this is an area of the ocean where, I think, previously we had no idea corals existed there.This is new news, and I heard you speak at the Kreeger Museum about this and you were saying that only in the last couple years have we managed to see some of these Corals in this Zone. And then if I can share one more to illustrate your range, I think in 2016 you had an exhibit, the Firewall exhibit, where you focused on censorship, but also on media and what people are exposed to and what people are interested in looking at specifically at China and the United States. In this exhibit you had an interactive element with two computer screens side by side where you had Google and Baidu (I think that's the pronunciation) and people would enter a search term and would see how that search term was turning out results in the United States and in China. This was to illustrate how certain topics had very different results.

This is just an incredible range and there's so much more, I encourage everyone to check out your website, but how do you characterize what it is that you're passionate about?

J: Yeah, that's a good question. So in all of my artwork I'm looking at the perception and the depiction of “The Other”. “The Other” could be through what we see in our search engines and internet culture portrayed, as you mentioned, in the Firewall Project… it could be “The Other” in terms of news stories that are minimized or not getting the attention they deserve in our journalistic mass media cycle, the corals. And it could also be the other in terms of transnational or Multicultural citizens who are not necessarily of American nationality, so they're foreigners or immigrants.

I think this interest in “The Other” stems from my own identity being the child of immigrants in America and being a visible minority: being female presenting, you know, yellow skin/black hair/brown eyes. It doesn't matter how American I am, I will never visually blend in as the mainstream. So “The Other” is a really potent experience in my life and I'm always interested in connecting with “The Other”, whether that's like an idea or a community of people, that's the one common thread that leads together everything in my art practice.

I am the kind of artist who's interested in ideas and then the material and medium follow, which is why I think I work in many different disciplines as far as video projection and installation photography, and now more and more sculpture and also socially engaged software like you mentioned in Firewall. So I think as my career is progressing I'm starting to limit the mediums I work in but the focus on “The Other” is always there.

R: I appreciate that so much as an immigrant myself. I was born in Czechoslovakia, we emigrated to Canada, and then I'm now trying to get a Green Card here in the United States. So I relate but I also know the privilege that I've experienced my whole life, where I can blend you know in whatever setting whether it was Canada or here. I appreciate you sharing that, and I'm I'm curious what you said about how your ideas have led and then your materials have followed. When you go back in time in your career was there a point at which you were more interested in just creating art and you weren't really sure what it was that you were wanting to create - you just wanted to be a maker? Or were there ideas leading even at that point?

J: You know, art for me was a second career. I started in advertising on Madison Avenue and because of 9-11 it was really an intentional decision that I made to shift gears to pursue art and so at that point I didn't know what I wanted to make. But it was really just about exploring mediums you know and as a child I could always draw and paint and so that's kind of where I started, but once I got into graduate school it was interesting. Maybe this is where “The Other” experience comes in. I realized very quickly that painting is a canon in art history that is really difficult to um tackle as an artist. It's very worthwhile, but the feedback I got in grad school made me realize like “okay, I have to pick my battles here and maybe it's not with painting”.

So at that point I was just thinking about making something personally meaningful. So I made a documentary about my grandmother and at the time she was 97. So this was like 2009. She was splitting her time between Taiwan and China, and my uncle and I really wanted to tell her story because I remember thinking - I guess I mean this sounds kind of grim to say - but the brevity of life has always been a really big motivator for me and making art, right, it's kind of why I became an artist after 9-11… So, in graduate school I was thinking about my grandmother and how, you know, she's really up there in her years and I didn't know how much time I would have with her left, and she's so far away… She was completely hard of hearing, so deaf, you know, she had lost all her hearing, so it was really difficult to communicate with her and I thought to myself how can I celebrate the person that she is: an incredibly strong woman that had her feet bound when she was 15. She was the last generation of women in China who had bound feet and it's just so wild to think about you know the Sino-Japanese war, and having her feet unbound by Japanese soldiers, and then immigrating to Taiwan where, you know, it was occupied by Japan for many years… So it was it was just a very complex history and thinking about what was her journey like as a woman and as a mother, right? And so at that point I decided, “okay I'm gonna make something personal, I don't know what I'm doing or where I'm going with this project”. But that was my very first video piece and at that time - software has changed so much - at that time everybody was using Final Cut Pro we were still shooting on SD videotapes so everything was still very analog, and at that point there was no like 4K video. DSLRs were just starting to be able to have video capacity, so it was really an interesting time for the discipline of video as a medium.

That was my first video, and in graduate school I got this overwhelming response and it was really surprising, but I realized like oh there's something valuable in my other perspective and in the life experience of my family that is so different than maybe the average American. And so I think at that point I realized like, “okay this is something I can focus on”, and every project moving forward - whether it was you know mining art history tradition of Western painting and thinking about the representation of the figure and the lack of you know faces that looks like mine or thinking about what we experienced day to day in representation of minority communities and social issues - that was kind of the turning point where I started to realize, like “okay I want to tell this story and the medium will follow the concept of the work”.

R: I've heard you say that you don't listen to the news or you don't watch the news and yet you're such a commentator on what's going on around us. I love what you're saying about “The Other” and about the interrelationships between us and others, all these different groups and the rest of the world, and so much of your work gets at that so I'm wondering what is your relationship with tracking what's happening? While simultaneously maintaining enough of a distance to form your own perspective?

J: yeah that's a really good question. So I'm actually a News Junkie. I love news, but the thing is I take it all in in the form of podcasts and I think part of that is because of such a visual person that the power of images and seeing so much on television or streaming online that can be disheartening whether it's human rights abuses or political geopolitical conflict it really impacts me, like I'm the kind of person that I can't watch a horror movie -

R: I can't either.

J: yeah those images will just stay with me.

R: You know, they do stay with you: science has shown that our minds can't distinguish [between what is fake and real], so unless maybe you're so desensitized, if you see something in a horror movie it seems it's real like on some level in your head.

J: So this is something I actually talk a lot about with my with my college students because you know having worked in the media industry I understand that media - mass media and journalism especially - is a product that's produced that's meant to be consumed just like this podcast that we're recording, right, and so I always think about the agency that the consumer can exert over their consumption to think about you know, “what do I want to expose myself to, what do I want to buy”, right, in terms of information, whether it's visual or audio or data - what do I want to buy that I think will in some way enrich or better my life.

I don't have anything against television or um you know watching the news. I'm just not the kind of person that that helps and so for me I take I you know I read the news and I listen to the news and I feel like that way I can kind of protect my interior world from being quote unquote manipulated or polluted perhaps by the onslaught of images that we see in mass media. I see that impact, I think, in my students that there are different generations, you know, and they grew up where everything is streamed online and at a pace that is really different than what I'm used to. So yeah it's shocking. It affects our attention spans, it affects our ability to focus, and so that's why I kind of have to distance myself a bit from the news cycle. But yet I also feel like it's incredibly important to stay aware of what's going on in the world around us.

R: I appreciate that so much and and I imagine that your interior world - you're mentioning the need to protect it - I imagine that you must have so much going on in there just gauging from from the huge range of work that I see and how you manage to explore so much so beautifully, and I wonder how you sort through your ideas? Because your projects - I imagine each of them takes so much time, so how do you filter, how do you figure out what you're going to commit yourself to?

J: So I would say for the last decade I've been primarily working in installation and as a result of that format I think oftentimes the exhibition venue does determine a lot of what I make and what I focus on. So for example the Mesophotic Sanctuary show, that was really a prompt that was given to me from the curator of the museum who wanted their entire summer season to focus on play and so as a result I was thinking about, you know, what environment do I play best in, what environments do I have access to play in, because of my class or my you know position in the world. But other times I make decisions solely based on my interest in medium, [...] but then when I have to like narrow down and edit what I focus on I do think about what kind of mediums. So I have a couple of projects that I've shown where I'm using video projection on glass and I just became so enamored with the interplay of light and refraction on that material and so glass has really been kind of guiding me as I work through future shows. So, yeah, so it's a little bit of both: sometimes the curators help me decide, sometimes I'm just following a medium that I really want to work more in.

You know, glass is a very specific world that's usually associated with craft and not with high end art [...] which could be, you know, a whole conversation, that could be its own podcast, but I think that does kind of help me narrow down what I want to focus on.

R: I didn't know that there was that connection to play, I must have missed that, and I'm curious: even though that was a prompt or an idea given to you from the curator, what do you think your relationship to play is generally in your practice and and how does it relate to to your engagement with the world?

J: I mean I think artists by nature always play, right, part of what we do in our studios is experiment without fear failure. And for me that means that sometimes I try really really outlandish ideas. Like my Firewall project was prompted by the death of a friend actually named Tytai who lived in China, and he took his own life actually. It's a very heavy serious subject thinking about young queer people in China and what kinds of pressures and um discrimination they face, but I also thought to myself, “what's the way that I can present this in a way that is more accessible for a large audience”.

That's where I got the crazy idea, like okay he loved to spend his time on Facebook and on social media interacting with Americans, but what was kind of the dark side of that? Like what did he see online or experiences in his interactions that maybe contributed to a negative self-view? And how could I turn that around for a broader audience so that they could experience that playful exploration of the internet but also see both the good and the bad, right? And so that's where I got the idea to create a dual browser search engine where people can surf the Internet on Google anywhere in the Western World and compare the results with the internet [in China].

That was this outlandish idea because I don't code, right, I just work digitally, but at that point I didn't know how to code and I just thought to myself like what if I could create this? So I started asking some friends who do code, like, “is this even possible?”, and they were like, “yes it is possible”, and so I found a collaborator, Dan Pfeiffer, who has done a lot of socially engaged creative code. He's married to an artist and I would call him a hacktivist: so he's a hacker and an activist. He was responsible for creating the dark web for a Zuccotti Park when Occupy Wall Street happened.

It was just this you know crazy idea, let's just play around and see what we can build, and it ended up working. I think that spirit of no idea is impossible, let's just see what kinds of creative responses we can come up with it has has been a big part of my practice. I think in terms of play recently the glass for me has been really fun because it's a different way of working in my studio where I'm not so screen based, you know using software and code to create something visually generative but instead using my hands to interact with their tactile material. So that has been so much fun for me to explore and I think I'm going to be integrating that more and more with the digital in my work as well it really feels like I'm just playing which is fun.

R: That's so great. It's lovely to hear more about the the background of the Firewall project and I also think that another thing that you do so well is that you have an interactive component to so much of what you. You're inviting people to play too and I think as we grow up, I don't know, I think everything is pushing us to to not play, and to see play as something really unserious. But I feel like play is a way for us to comprehend the world, as a way to engage more creatively. I mean, if artists can provide that for people- and I think you do that - that's just like one incredible role that art can play in society.

J: Thank you. Yeah I was I was actually um just part of the Games and Emerging Media Faculty candidate search at Maris College where I teach and that's something that's a really big field of creative research, “serious play”, and how can serious play really be impactful in a way that you know other means of engagement can't materialize. How can putting the audience or like an intended participant into a playful atmosphere how can that engage them in serious issues that are otherwise really difficult.

R: That's so cool. I work in the humanitarian sector um quite a bit and I have a couple collaborators who are really into games and bring games into policy maker settings and it's been it's been cool to see how dialogue can be sparked and people can just reach more generative collaborative spaces like when they are I guess like pushed through some sort of discomfort, or just like maybe it's the element of surprise, I don't know. But it's great that you're exploring that too.

Just to go back to your Firewall project: I read in one of your interviews that you, I think you use the word naive, that you were naively surprised at how much of an impact it had, and thinking specifically, I mean I think there was a lot of interest generated, but you were I believe thinking specifically about the attention you got from the Chinese government, and you had a number of people who were going to be engaging with you or there was there was one person in particular who was going to be I think speaking at a launch, and and they had to back out because they couldn't receive that kind of attention and scrutiny. And you were being surveilled at this point and I'm curious whether in hindsight you think that that was that was a great success, you know to see that you could have that much impact on cultural discourse, that you could garner that kind of attention. What was your experience like with that?

J: So I hesitate to say that it was successful just because I think that judging the success of artwork in general is a very complex issue issue, right, and so one could say Firewall was successful because it got a lot of press. One could also say that Firewall is very successful because it did garner a response from Chinese authorities. However as an artist, as a content creator, I think recognition can be a troublesome ambition, right, and so do I think the project reached a big audience? Yes. Do I wish it happened through a Chinese National in this case it was a human rights lawyer [...]. She's now an American citizen but like do I think her being targeted by the Chinese government was a success, no I don't, you know, and so I would say I was very naive going into the into this field. It was my first time making artwork that was … I mean Firewall…. I would not say Firewall is a political project, I would say it's a human rights you know it's a humane project that really focuses on this portrayal of how the internet can manipulate our access to information both through State authorities from authoritarian governments like the Chinese government but also from large corporations like Google who exercise corporate censorship and you know definitely exert bias in our media, right. But I think maybe the success of the project for me as the maker is that I learned that art really can have an impact. We hear this all the time, but it was my first time really experiencing that on the ground where I put together an exhibition and it was funded by a couple of Grants (from the Lower Manhattan cultural Council Asian women giving Circle and the Franklin Furnace fund).

Perhaps that funding is what increased its visibility, I'm not really sure but it was like I was putting something out in the world and the response was much bigger than I anticipated and so the Chinese government did hear about it and unfortunately they did intervene and they tried to censor our event, which was a bunch of Chinese feminists speaking about how the internet plays a role in their activism for various issues. We had speakers who were presenting on queer rights in China others were talking about kind of the role of unwed older women in China and how they are often called a lot of derogatory terms and not seen to have social value, and then the woman who was targeted (the lawyer), she was speaking about women's Reproductive Rights in China and how the single child policy led to a lot of abusive practices [...]

There were civilian spies who came to our event because they did not want this human rights lawyer to speak about her work. At the time she was a fellow at the Yale China Center… The Yale Law China Center, which has changed names now but I think it's Paul, I have to look it up but Paul something China Law Center, and uh they, you know, they really didn't want that to happen so we had a very tight RSVP list because we are potentially sensitive. I had spoken to some human rights workers but since I was new at this, I'm just an artist, did not technically know the dangers, and so these civilian spies showed up and nobody knew who they were but they were clearly foreign, not of the art world, they stuck out like a sore thumb. They wanted to prevent [the lawyer] presenting yeah and she didn't present but the other Scholars at Yale are really dedicated to the issue so they did send a translator to come and present about her work and that translator was American.

So, you know, I learned the power of of my voice and the voice of activists through that project and I learned that what I make does have consequences and not just for myself for other people, and so now as an artist who wants to continue making socially engaged art I do have a very different model of stewardship that I think about as I'm starting a project and I think about how can I tackle an issue with responsible care for everybody involved. That does mean recognizing my position of privilege as an American that others may not share. How can I elevate, you know, a cause where citizens of other countries could be affected without endangering anybody. I do think about that.

R: Oh and I imagine it must be tough now to think through… following that event, I'm curious if you came out of that feeling like having some sort of tangible impact, like whether that that became almost like a marker for you or something to reach towards or if you felt like that was something that you needed to not think about? That just seems very tricky right because you talk about how now now you're trying to build in these safeguards into the way you work and I imagine that that maybe keeps you out of of some of the more tricky situations but then on the other hand you sort of want to be stirring the pot a little bit?

J: After that original exhibition in 2016 of Firewall a non-profit organization called the Human Rights Foundation reached out to me and so Firewall has been exhibited at their Oslo Freedom Forums for several years and that was a really big learning opportunity. It has been a very big opportunity for me to be involved with this organization because their belief is… they're a very libertarian organization which like I'm not personally a Libertarian, but I would say that one of the strengths of Libertarians is that when there is a justice issue at hand they're not waiting for governments to organize and so part of the motivation behind these conferences is they bring together activists um usually very young emerging world leaders, technologists, people who have kind of creative solutions to these different human rights abuses and they have a platform to be able to communicate and distribute about artists like myself who think out of the box.

So I've really learned that these conferences… that you know that balance of trying to engage an issue and make some small steps towards justice is a balance between protection and self-care and I see that a lot with activists young activists like burnout is real and um being oppressed is real and being persecuted is real and then at the same time I see a lot of hope that when people from different disciplines are willing to work together and think creatively there can be some solutions, or at least some small steps towards that. So I guess to answer your question, where I've arrived personally is that Firewall is still going to be continually evolving. I'm working with a new developer Angelique de Castro who works at the New York Times as a software developer or software engineer, and so we're trying to come up with a new Firewall that people can experience from home. So that will engage audiences more broadly and from safety of their own home.

But also um I have kind of distanced myself a little bit from making work that is so overtly political. The project I made immediately after Firewall was VertiCal, the project that you mentioned at the beginning, about the travel ban that Trump initiated in the U.S against uh people from Middle Eastern and North African countries. I wanted to address that, but in a completely poetic and abstract way, and so I feel like I've been trying to find the right ground to stand on as an artist between making work about justice issues that I really care about while also walking a very fine line of impact with what I create initially. I haven't figured out the balance but I'm trying to figure that out.

R: Maybe a lifelong pursuit and you also spoke about creating collaboratively and I can see that much of your work seems to be collaborative in one way or another: you have created with children at the Metropolitan Museum … there's this incredible collaboration you did with your mother during the pandemic where your mother was collecting … was recording daily death tolls, I believe from different cities around the world, and you ended up doing some projection work around that… and you also did this great project with Asian American I believe women or women identifying individuals about soft solidarity and that was in response to the rise of anti-asian hatred that we were seeing that we I guess are still seeing unfortunately here in the United States.

I imagine the collaborative work… from my perspective it seems very essential, like when we're dealing with social issues it seems like it's difficult to be working in an isolated manner and I'm wondering how you've shaped your practice? How do you balance your own ideas with wanting to be more in a collective?

J: Collaboration really is key for me as a creative person. I know a lot of artists work solo in their studios but I think because so much of my work is motivated by larger social issues that are outside of myself and in some cases even external to my own direct experience operation it’s key. Some of it is just logistical, like my ideas are bigger than the skills I have and so that necessitates um collaborating with software engineers and um Glass artists who are master glassblowers from Murano for example, but oftentimes I also think that with more intimate collaborations, like the one you mentioned with my mother… oftentimes I am inspired by the creative processes of other people as well. So you know my mother worked as an accountant? She's now retired, but she has always been a painter. She does Chinese calligraphy and painting and now that she's retired that's something we talk a lot about because she's a big reason for why I became an artist. Now that she's retired um she's always talked about wanting to focus on her art herself and so it’s kind of an ongoing discussion, but when I saw that she was obsessively recording these death total numbers during covid I thought to myself, “this is such a beautiful act of empathy”. I asked her, “why are you doing this”, and she said, “well we see these numbers displayed in the news and it's hard to imagine the scale of death like that. You know you see like thousands of people per day die, what does that even mean?”. So in her act of recording… right, she's a teacher at heart…

That kind of transcription that happens between our intellectual understanding of something and then enacting it through a bodily performance. This ritual of writing down numbers every day helps embed the truth of this information that she's - that we were all - getting at that time during covid. That’s really a discipline and that skill was so inspiring to me and I thought to myself, “I want to honor this effort that she's put in and I also want to encourage her to keep on doing it”. So we decided to do that because she was like, “are you sure you want me to keep recording these numbers”, I'm like “yes”. So we had this kind of ongoing thing where she would mail me the numbers.

So collaboration feeds my own practice and also enables it to expand to a scale that I want my ideas to to be materialized.

R: Beautiful… I have a question about elitism. Much of what you address gets at different social issues and there's some socioeconomic elements to what you have addressed in your work. I'm wondering how you reconcile with I think being predominantly in these elite institutions very often? You know, spaces that even if the admission is free, some people just don't feel like they are welcome in those spaces I wonder if you've thought about this. How you reconcile that for yourself?

J: Yeah I have thought about it. I mean, I'm admittedly very privileged. You know my parents came to this country without much money but they were educated and that is its own form of elitism. As a college professor I can say you know education is really a privilege and it's expensive these days. As an educator the one thing I think about is, I mean kind of in the same way that I do try to protect myself from the visual stimulus and onslaught of the news cycle, I think about that in terms of like my own position in the world too. So with the project that you mentioned with children at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that was an invitation from a curator for their World Culture Day that they have every year.

I've always loved children, right, but it was a good challenge for me to think about how can I make the ideas that I think about, that are sometimes very complex and difficult for children to understand, how can I distill that into a simple engaging experience that is focused on tactile and easy translation of Big Ideas, right? So that's an example where I think a lot about accessibility for my practice.

We were making these simple little light boxes that would project their drawings onto the wall just through markers and some acetate that we fold into these origami forms and then they would use their cell phone and flashlights to shine their drawings onto these giant weather balloons that we suspended into the space at the Met. We created this Cosmic Universe… but the question to the children was, “what kind of future do you envision, what kind of world do you want?”. That's a very open-ended question. Even though I have a vision as as an artist for what I would want I really want the response to be very Democratic so anybody can participate and every mark is like equally valued in that space as far as how you draw, what you write. I learned so much from the children that participated and from my students every day.

So I think one way to kind of combat elitism is to really recognize the humanity in all people regardless of age, gender orientation, sex, background… and to affirm and validate those ideas even if they're totally different from my own. That's difficult to do through art making because oftentimes art making can be very pedantic but I'm more interested in my art of creating this environment for discussion.

The Firewall project is like that or even the VertiCal project… like somebody could walk into the installation that I made of the virtual prayer rug not recognizing what it is but hopefully become intrigued by walking on these patterns or experiencing the interactivity of the motion sensor. And when they ask the questions then that's my opportunity to speak my vision or my messages.

I think it's really important for people to ask questions if we want to combat elitism and to really listen well. I'm not saying I've figured that out in my art practice, but I do think that a lot of my projects are structured to be in an environment that can prompt question asking. Hopefully the environment is meditative or inspires reflection in some way that promotes listening.

R: speaking of the environment I heard you mention that your relationship to the environment deepened during the pandemic because I think you were encountering or engaging with nature in different ways. Now you have some pieces or at least I've noticed some pieces that engage with the environment or raise questions about our relationship to the environment or they’re on climate change. How do you think that connects into your social commentary work and how has that environment relationship for you been shaped?

J: I guess I was thinking about you know during covid shutdown everybody was so cloistered in their own homes. I think for many people around the world one of the reliefs from being quarantined, or from a city being shut down like in New York, was to go outdoors. I remember listening on the news to these very complex issues - especially in New York City - of access to green space. This is something that exists in a lot of large cities. The way cities were developed and unfortunately the way zoning or redlining may have happened in the past there are marginalized communities that exist in very concentrated spaces without access to green space. Without access to parks.

And I remember listening to that and then also at the same time hearing about these Russian oligarchs whose yachts have been confiscated at the start of the Russian-Ukrainian war. I realized the immense amount of wealth that was represented by these ships, you know like a yacht is millions of dollars, and what is the purpose of that? Yeah it is just so very elite population can explore a part of our globe and the natural world around us that most people who are just common citizens would never get to experience. So it was this weird realization that this was happening around me. I was really craving going on hikes and going outside and being immersed in a space that was not my home, then hearing about this stark contrast and accessibility with being able to enjoy our natural world. So that's kind of where I became interested in making work that was about the environment. The story that I latched on to was the scientific discoveries of the mesophotic zone, right, which most people haven't seen, really just scientists have been exploring. But like with all coral reefs around the world they eventually become tourist destinations, right. Because of our action, because of people's leisure activity we're also in many ways damaging our globe and our natural resources and coral bleaching... It’s one of my life's dreams to go to the Great Barrier Reef, but I don't know if I'll ever get to go because it's being you know decimated by global warming, acidification of our oceans, temperatures rising. I wanted to just celebrate this amazing little news story that I heard about coral adapting at a deeper depth of the ocean than previously thought possible. That none of us are able right now to explore, but if we could access everybody could break from our regular earthly existence and be immersed in something that is just beautiful and strange and foreign. [I thought], how do I do that through my artwork.

I guess I've never really thought about global warming and climate change as a justice issue but I think after going through the pandemic I do see that it is engaged in in many issues around class and access in a way that I previously hadn't thought about.

R: oh yeah so much and you're saying that these yacht dwellers, that they like get to go and explore these parts of nature and I would say, I mean not knowing any personally, but I doubt so much that they're out there exploring nature… they don't even care. It’s devastating, and then what's wonderful though is that you can create an artwork that can connect people to a place that they might never see and they don't necessarily even need access to such a monstrosity.

You're a teacher and it seems like to me - and please correct me if I'm wrong - but it seems like you believe that you have like some kind of responsibility to society, to your surroundings in some kind of way, and I'm wondering if you think that's true, and if you think that artists writ large have a societal responsibility?

J: I definitely personally feel responsibility. I think that we have one life to live and I want to make mine count. So even if that's just through transforming the understanding of our world one student at a time as an art professor… I think that's meaningful. Recently I had a student who took a semester off due to some health issues send me a gift in the mail. She sent me this amethyst geode and she wrote just a simple letter, but it crystallized why I teach. She talked about how in all of her struggles in college and with her health that talking with me about her artwork was really always this moment of light and love. So she wanted me to have this crystal in my office to remind myself of that. I was so moved by that gift you know and I think these are the kinds of moments and transformations that keep me motivated as a teacher even though it can be challenging and you know our higher education system has a lot of its own problems.

But I do feel that responsibility. so if I can't achieve this kind of awareness or understanding through recognition in the art world if I can do it through education like I'm happy to do that. Whether or not I think all artists writ large have this responsibility is a really good question. I think that the decision to become an artist is a very personal one and so for many artists it's about self-expression. I think for me there's definitely that involved but I see it as a way to communicate through the visual world by creating content that can connect and communicate about larger issues.

So I don't know if I would say that every artist has [that responsibility]. I think for some artists the process of making art and just expressing themselves is something that they need to live and I'm not sure that there is a larger goal for social good and that's okay. I think that's actually fine because I think what makes art resonate is when the artist is able to be genuine with what they feel called to do. That is different for everyone.

R: It's a beautiful answer and I know we've been talking for a long time so I want to just ask a couple more questions… Hopefully you don't feel the need to take so much time with these ones because they're just more of these rapid fire types okay so you can go on with your day and do other important things:).

I'm curious what's coming up for you in terms of art and projects that we can look forward to and that you're looking forward to?

J: I'm going to be part of a group show in the summer. I don't remember what it's called right now so I'll find out what it's called.

R: We'll put in the show notes.

J: yeah it's at Five Miles Gallery in Brooklyn. It'll be a group show that's curated by Sophia Ma and a leader of a group that I've been involved in called Asian-ish which is a group of artists writers and curators who are asian-ish in identities so they may be bicultural, Multicultural, cross-cultural, transnational like me. But it's a show that's also about solidarity. That's a show that I'm really excited about.

I will be releasing the updated version of Firewall sometime this year as well. We don't have an exact deadline but it's going to be a web-based app and so I would love for people to try it out and give me feedback.

And then lastly I'm just working on a lot of new class projects and I don't even have a show scheduled in mind for them. But things always to come up so something will happen.

R: That sounds like a lot of good things coming up. I'm curious, I had asked you if you would be willing to share three artists that have inspired you or shaped your worldview or how you engage with your art in the world. You mentioned you might have an organization also to share as a third one.

J: Yeah well I think I have just thought of a third: So James Terrel is a light artist from the 70s that really opened my eyes to the transformative power of light and what it can do to a space. He's also an artist that really has a profound relationship with the Earth. He's a light artist, but I would also call him an earthworks artist, and he's been working on Rodan Crater in New Mexico which will probably be his lifelong Legacy and a way to use nature to really provide us an unusual glimpse of the night sky. So he's one artist.

The second artist would be Pipilotti Rist. I think she's Swiss. I would have to double check that but I think she's a Swiss artist that creates really fun and playful video installations that just really opened my eyes to what it means to play as an artist, and to create really unexpected environments for people to immerse themselves in through video and light.

Then lastly I would say that Ai Weiwei is a big influence on me. He's a dissident artist from China who creates conceptual sculpture, and has recently also been making documentaries himself. I think he's an artist that really understands the role of education and class. He's the child of a very famous poet who was imprisoned during the cultural revolution. He's used his art practice to open eyes to the history of China and some of the human rights issues that still plague that country.

R: Thanks Joyce, and finally do you have one piece of homework? You’re a professor, do you have homework for the audience? Something to do or think about or look into… a question to ask?

J: Yeah I would say that the next time you're in a debate with a friend or a family member about an issue, I challenge our listeners to really pause and think about the perspective of the other. Before you blurt out your answer or your own perspective to just pause and really reflect on what that other person is thinking or feeling and try to see if you might put yourself in their shoes. Try to empathize with their point of view before you speak.

R: That's beautiful and that's a perfect full circle movement coming back to “The Other”, because that's where we started the conversation. Joyce thank you so much for your time this has been just such a gift and I've learned so much.

J: oh it was so fun and I'm really um happy to participate and be part of your new podcast.

R: Thanks so much.

[Music]

That is it for this episode. Thank you for sharing this space and time with us. If you have any ideas for who I else could converse with here please do get in touch at hello@the-heart-gallery.org. I also welcome any other thoughts about the podcast there, you can also find me @rebekaryvola, and it would be lovely to have your support in the form of podcast subscribing wherever you listen, rating, commenting, and sharing with others.

Thank you also goes to Samuel Cunningham for the podcast editing and to Cosmo Sheldrake for the podcast music. I encourage you to go find the whole song, it’s called Pelicans We. Until next time!

[Music]