Weird Stories; If Fog Could Sing

The shorter fiction, dramas, and poems of Charlie Price, read/performed by Charlie and Robert Price.

Dark, surreal, comic, and peculiar stories of life, human nature, and the shadows within.

Weird Stories; If Fog Could Sing

Bonus Episode: The Song of the Physician

“Who hath dared to wound thee?” cried the Giant; “tell me, that I may take my big sword and slay him.”

“Nay!” answered the child; “but these are the wounds of Love.”

The Selfish Giant, Oscar Wilde

The Song of the Physician

The profession is chattering. Their teeth are chattering. They are chatting amongst themselves. So easy to confuse chatting and chattering. At any rate, they are talking, and they are talking about me. As I speak, not aloud for fear of being heard, not that I would have been heard anyway, but this that I have to say, explicate, elucidate quite specifically is for no ears but those that symmetrically adorn either side of my own cranium, a monograph entitled Ethical Considerations Surrounding The Naming of Congenital, Hereditary, and Contagious Diseases is being peer reviewed. I am not the be-all-and-end-all, nor the monograph’s soul subject, but I am the inciting offender, I am the prompting deviant, the controversy hovers around my name, hotly.

In a nutshell, I named a terrifying dermatological disease after my eldest son. So, simply, Ethan’s Flesh Disease. The first inexplicable and seemingly arbitrary sufferer must of course be mentioned. Her name was Melanie Ant.

It had been a sad, sunny day. I sat at my desk, labcoated, thermometers and stethoscope heavy upon my person. Why so sad and bad? Things were very bad between myself and Stevie. That’s what people say, isn’t it? Things were bad between us. The birds were singing futilely beyond the windowpanes. Then Melanie entered my practice, clinging to her eldest son’s arm almost conjugally. Her spouse had been dead for some time. She had known bereavement for some time, she was and remains in her sixties; the love of her life had been many years her senior and had died while she was not yet fifty. So, her grown-up son was the closest available male to her. At my invitation, as soon as the usual interview ahead of examination was completed, she lay down upon the gurney, pulled up her blouse, and revealed her ailment to me.

Her stomach was enwombed in a horrifying red, a shade of that urgent, primal, volcanic colour I have yet to discover in the natural world, or the unnatural world for that matter. Within that unnerving patch- more a pool really- of red discolouration, the textured tints were even more remarkable, the stuff of awful legend, yet to find itself such. It now is awful legend, thanks to the periodical I was bound by professional code to publish. Within the outer discolouration, small, lumpy buboes of yellow pus- (what I call “pukerous noxes”)- congregated, variously saffron and fiery. I hazarded a guess right away that the affliction was a case of unusually aggressive chancrous syphilis, but, taking her word on the matter to be truthful, she had been intimate with nobody in over five years.

This was simply the beginning. Melanie Ant came in regularly for evaluation. I had her scanned and later biopsied. At first the appointments were simply regulatory. She complained of no especial agony, simply a great sense of revulsion and trepidation before the crimson thing on her stomach. Absolutely understandable.

However, every time we met, the symptoms changed. Or perhaps rather, the symptoms didn’t change, the principal symptom’s colour changed. The second consultation saw the main, outer discolouration change to a nocturnal violet, and the little buboes and roughnesses within become a bright, lurid green.

The agony finally did arrive, at which point it became essential to examine the inner composition of the pustles on her stomach. The various treatments prescribed thus far had afforded Melanie no relief, in fact the prescription for Bellium Cream to be manually administered to the affected area had probably done more to irritate than relieve the symptoms. For the intense sensation, which she described variously as tearing, burning, scraping, she was given a controlled dose of morphine. She also complained of early satiety, a symptom that most commonly betrays stomach cancer, but no such cancer was subsequently found.

Then, under anaesthetic, I punctured one of the carbuncular growths and extracted its substance. This I carefully preserved, packaged and sent to the lab for analysis. The results struggled to make sense of the chancres’ chemical and biological composition. They simply seemed an extension of her, they didn’t seem to think of themselves as a manifestation of ailment, as terrible as they looked.

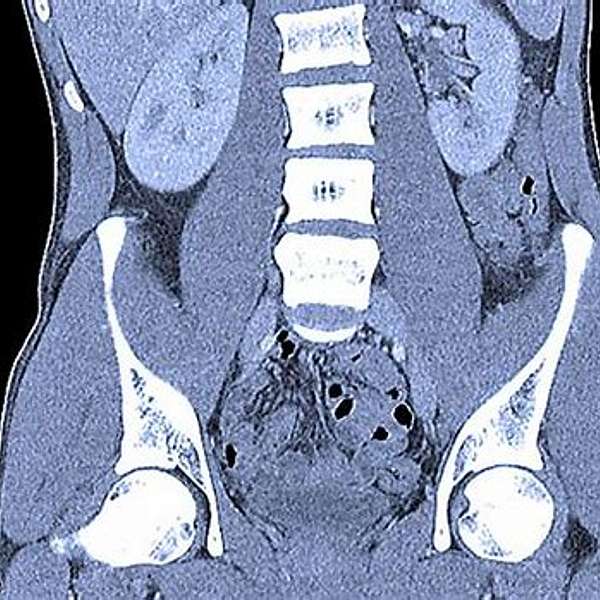

What the scan showed on the screen was shocking. On the nocturnal coloured screen, as Melanie Ant entered the sterile, white tunnel where the examining light was bright and various censors hummed with their cerebral efforts, the glowing, greenish outline of a body gradually filled with its inner substance. The body of the patient itself revealed various symptoms usually associated with the menopause, though the menopause was long behind her. Relatively healthy organ function for a woman of her age presented itself. But the rather visceral, colourful disturbance upon her skin, the focus of our investigation, seemed to have no cause beneath it, none whatever. Such a physical symptom on the flesh, and apparently, it had no structural basis underneath it.

Blood disease of some kind also seemed possible, or poison, some kind of strong, negative reaction to something she was consuming. But her O positive blood showed no signs of cellular mutation, or foreign contamination.

It is something of a mantra for me, to try and keep one’s sense holistic, to maintain holistic vision of a patient. Heaven forefend that we should ever forget the blood running in our patient’s veins, the red thump of the aorta, the heave one way and the other of diastole and systole, the motion of the bowels, the habits of the genitals, the blue shocks and teeming flashes of the synapses, the thinking, dreaming, remembering parcel of the brain inside the skull. It has been known to occur that certain fascinations with pathology or retardation or mutation of any kind, have blinded a physician to the humanity of their subject, and sight has consequently been lost of their duty of care. In the intensity of their investigation, the beautiful enigma of diseases or conditions glimpsed for the first time in the human body have sometimes led doctors to forget the conditions of the Hippocratic oath. I was determined that I should not lose sight of Melanie Ant’s humanity, as new and significant and mesmeric as this seemingly extra-human affliction of hers was.

Many tests were conducted over the next two days. A coma was medically induced to allow for more thorough investigation. The findings were published. To understand, please read my monograph on Ethan’s Flesh Disease. But the name…therein lies the crux of the matter. Why did I name the disease after my eldest son?

Stevie was the one who leaked it to a medical affairs correspondent that Ethan was the name of our eldest son and that was the only possible reason that I had for naming the newest disease known to the medical profession Ethan’s Flesh Disease. There was no other possible correlation between the name Ethan, and either the disease, or Melanie, or myself. It was an act of revenge, to sabotage my reputation. I picked up the phone, ready to roar into the receiver every name and every barb that I knew would wound her. I forgive her, completely.

Towards the end of the two days of medical sleep, finally Melanie’s face seemed to soften. Peace rather than pathos seemed to flood the somewhat coruscated face, in its reddish unconsciousness. I would not lose sight of her. In something like prayer, in secular meditation, I sat at her feet and cast my eyes over that sixty-seven-year-old body, well preserved for the most part, a little sunken in places with the wear and tear of age and sadness, unalarming but for the massive discoloured, carbuncular blob in the middle of her stomach. A symptom is the body’s way of communicating distress, the body’s way of speaking in times of trouble. We should listen. So I listened. Quite literally I put my ear to her red patch (which seemed always to revert to red, but had variously been green, blue, violet, lavender, lilac, yellow, orange, and so many lurid, indescribable, noxious-looking mixtures of all of them and more). I put my ear upon what could be incorrectly but somehow aptly described as a wound. It was not the result of physical injury of course and yet it did seem to me almost as if it was. We had determined that it was not contagious and so, from the point of view of my own wellbeing, I had no fear her condition.

In the wound, through my ear’s intimate congress with its colourful parameters, I heard a voice. I initially thought it was a woman’s voice, singing highly, angelically, arch-angelically. Somehow I was able to tell that it wasn’t a woman’s voice, it was a little boy’s voice. Long lines of unintelligible melisma rolled from him and sang in the wound (it seemed) and entered me, through my ear. Wordlessly, pure-musically, in unending melody, he sang.

Such a bright clear voice, as though beneath the diabolical mess of her disease, there was an angel in her womb, a cherub, stabbing upwards with a rapier of song. It even hurt a little to listen to, so penetrating was its strange, sonic beauty. Muffled at first, gradually it became clear, with a point like glass. I pulled away and realised that I was breathless, and gleaming with sweat. I listened to the quiet of the ward, the corridors. There was no-one in the building. I was quite alone. No question, the sound came from her symptom, or from within her, beneath it.

I touched the mess of her wound, her patch of ailment. I ran my hands over its texture, felt its hard, ribbed surface. It felt like dried seaweed, like a dried seasponge, like a stretched raison-skin. As my fingertips explored it, for the first time- learning her ailment for the first time not through scientific but through sensory investigation, through touch, the singing of the little boy I had just heard for the first time grew louder, it intensified. I was standing up, my face about half a metre away from the affected outer abdominal area, now the singing, the voice prolonged and raised, made rapturous in the holily unctuous rapture of sustained pitch, was loud, like it was in my brain. I thought it had been in her, now it was clear that it was in me. But should I withdraw my fingers, the little boy’s voice disappeared, into nothing. The sudden silence of the little boy at my withdrawal terrified me, panicked me. So I pressed my palms tightly upon Melanie’s stomach, where the symptom was, and unchanged.

After a moment of pressing tightly to it, as though to a teat-like source of life, it responded to the touch of my hand. The entire area of the lesion began to shift, bubble, ripple, and from this marsh of terrific, malevolent red, a vision, ghostly, pale, white like milk rose up and looked at me. It was a woman. It was a woman I didn’t know. And in her womb she carried a child who seemed to be crying. But he was, in fact, singing to me. The O of foetal anguish was simply the shape that his mouth made while he sang while he sang with the joy of dumb, cellular vitality from within his mother’s womb I didn’t know the woman who rose up from Melanie Ant the vision produced by this area of affliction this symptom of a symptom this beautiful symptom of an ugly symptom but she was kindly and she bore in her womb what I knew to be my son Ethan not a second him not a genuine him but a reminder of him a vision remembered witnessed and of him whom it had all been for who was the gift that made the sweat worthwhile that gave me hope that gave me the strength to peer into the wound and into the smelliness and into the chancres and the buboes and the pus and the illness and the grief for love sprang from her wound and I named the wound after him and I am not ashamed.