Terrible. Happy

Mostly skateboarders. You Good?

New guest EVERY SUNDAY.

Host: Shan

Terrible. Happy

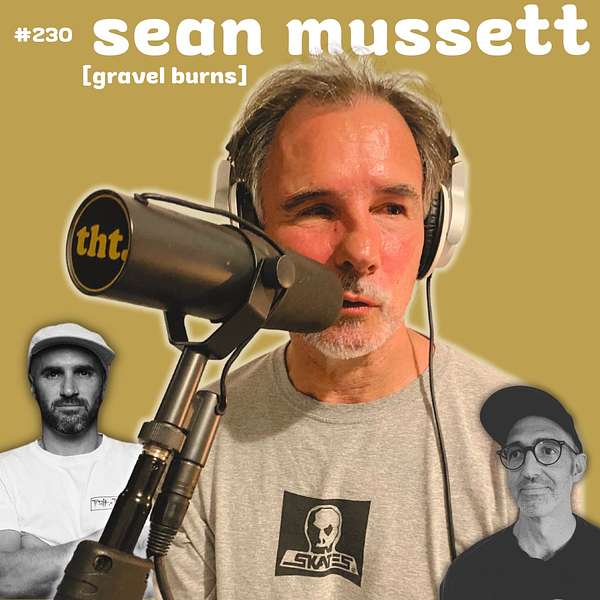

#230 - Sean Mussett: The art of not being a dick.

Nostalgia hits hard as Sean Mussett, the one-eyed legend of Australian skateboarding, takes us back to the gritty golden era where the skate scene was as raw as the elbows we scraped. With his tales of vert ramps and punk bands, Sean – our very own Gravel Burns – pairs up with skate historian Jim Turvey to lace up the narrative with rich skateboarding lore. Their stories span from the iconic "drain" to the Mereweather ramp and beyond, painting a vibrant picture of friendship, rebellion, and a shared passion for skateboarding.

We explore the deeper imprints of skate culture on personal growth and societal shifts. Sean's path from a visually impaired kid to an inspirational figure in both the skate and education worlds is a testament to resilience. The conversation takes a dive into the reinvention of school learning amid government lockdowns, how skateboarding blurs the lines between sport, art, and entrepreneurship, and the interplay between generational trauma and progressive shifts in community values. Yes, we go deep, and the topics are stacked. We don't hold back.

Wrapping up, we're not just talking about perfecting fakie pop-tarts on vert ramps; it's about embracing the ethos of kindness and positivity Sean embodies. This ride isn't only about the thrill; it's a life lesson in authenticity, the importance of staying true to oneself, and fostering a legacy of improvement for our youngsters. So, hit play and join us on a journey through time, culture, and the life-affirming philosophy of "not being a dick".

Enjoy,

Shan

THT gets by with a little help from these friends...

(Intro) Music by Def Wish Cast.

Song: Forever

Album: The Evolution Machine

www.defwishcast.com.au

https://defwishcastofficial.bandcamp.com/

INDOSOLE - Sustainable footwear

Code: THT

(15% discount shipping is WORLDWIDE and fast).

Sandals made from recycled Tyres. Timeless footwear for the conscious consumer.

BELLMOTT - Ready to drink Coffee

Code: THT

(Get 15% off your first two online purchases).

Pre-mixed cans of coffee goodness, Iced Lattes and more. Ethically sourced coffee beans, made in Australia, made my Musicians, Skateboarders and Artists. It's all about caffeinating culture, inspired conversations and shared creativity.

KRUSH ORGANICS - CBD oils and topicals

Code: THT

(Get a HUGE 40% Discount...shipping is WORLDWIDE and fast).

Purveyors of the finest CBD oils and topicals. I think long and hard about who I want to be affiliated with. Do the research yourself, the health benefits of CBD are unquestionable. It’s done so much fo

Printing custom gear for skate shops, brands and anyone building something cool.

Hit up them up for a FREE quote: print@trap-door.com

Or through their socials: @trapdoor.print and @trapdoor.dist

FINANCIALLY SUPPORT THE SHOW

Follow on Instagram

Follow on Facebook

Hey, it's Shan here. This week I catch up with Sean Mussett. Sean is affectionately known by his friends as Gravel Burns, legendary Australian skateboarder, originally from Coffs Harbour and also Newcastle, australia. Old vert skater from way back in the day we're talking back in the day 70s OG of Australian skateboarding and he sits down for a long conversation about his life music, art, he's designed graphics for skateboards, been the front man of punk bands and skateboarded his whole life. Sean is very open about sharing, about how he lost the sight in his right eye as a little baby and, yeah, an amazing skateboarder, like he says, with one eye, one-eyed skateboarder. It's really inspiring, actually. And he's an educator as well of students that are behaviorally challenged and we talk about our views on education as well. So we go deep on a bunch of stuff, but we do talk a lot about skateboarding For you skate nerds out there, you'll definitely get your fix.

Speaker 2:In this episode we're joined by past guest skate historian, journalist, article writer, photographer, librarian. Mr Jim Turvey sits in to add his two cents and probably bring some um fact checking to some of the stuff we discussed, sort of. But yeah, jim's just such a rad vibe, I love having him around and um, he's also very, very close friend of of sean, so you know the vibe between the two was just epic. I love that. And hey and hey, listen, while you get a chance, go over and follow the Good Push. Past guest Nathan Keely will be riding his skateboard unassisted, pushing all the way from Port Macquarie to Newcastle. It's over 300 kilometers and he's raising awareness in order to prevent suicide and raising funds for awesome initiative. Talk to me, bro. So follow him on Instagram the good push or Nathan Keely and donate to the GoFundMe he has running at the moment. It's a good cause. There you go.

Speaker 1:All right, Woo, I shave once a week. Whether I'm in the room, Really you look pinker. No, it all happened to me shaving yesterday. It was me shaving yesterday. I mean with the clip I don the car. Really you look really pink, huh? No, that's me shaving yesterday. This is me shaving yesterday? I mean with the clip, I don't know, yeah, yeah, yeah. I haven't shaved with a razor since I was like 17. No, it feels weird when you do, or weddings I think Luke O'Donnell's wedding maybe Really.

Speaker 2:How old are your kids, your eldest kids?

Speaker 1:your eldest kid, my own son, is 25. Wow, just about 24, turning 25. Dude, is that a trip? Yep, it's amazing why it's. Why is it a trip? Yeah, it's just because in my head, in my head I'm 25, like that's the age I am, like he's about to turn my go-to age. So it's like, how can that be? And he doesn't like he is like me, but he doesn't look like me. So it's kind of like he's massive, like he's Jim's height probably, and another five kilos, and it's just so. It's the weirdest thing. Like I said before, I see him all the time we go to the pub and it's just like you're my mate, but you you're not. You're my kid. It's such.

Speaker 2:It's the weirdest thing really is if you had to go back to 25 year old sean, what would you say to him?

Speaker 1:to 25 year old sean. Oh, it'll be okay, it's gonna be fine. Uh, yeah, I wouldn't. I wouldn't go back and say maybe I'd say buy more houses in Mayfield Probably. I feel like that would have been a really good bit of advice.

Speaker 2:Why is that popping off? Is that?

Speaker 1:No, well, I had a couple and they were like we bought I had like three houses with a combined mortgage of less than $200,000. So if I had 10, I wouldn't be working for the Department of Education. Really, Probably Real estate mogul, that was my partner. My son's mum was really into the idea of that, like, buy property, not develop it, but just hang on to it and get more and that's your retirement plan. And we had a pretty good go at it, to be honest.

Speaker 3:What year was that that you were purchasing property in newcastle?

Speaker 1:90. I think we bought our first house in 94. Like by 96 we had three houses, yeah, and it was just dumb. It's just dumb, dumb, like as in dumb luck. Like I remember I didn't have a job. I came back from Port Macquarie to go to uni.

Speaker 1:I finished uni and my grandfather had sort of done pretty well in business and he had like this bit of money for each grandchild and it was like $20,000 or something, which was like a million dollars in the 90s, and every grandkid could access this money. And I remember saying to my dad oh, do you reckon I could talk to Grandpa about getting this money for a house deposit? And he's like, sure, but you know, you don't have a job, you can't go to the bank and say I've got this $20,000, can you give me the other 50 just for fun? He said like it just didn't work and he goes oh, I can get a job, but can I get the money off, grandpa? And he goes, sure. So I sorted that out and like a week later I had a job, two weeks later I had a house. My dad still makes his head spin when he thinks about it. It was just the funniest thing.

Speaker 3:Wow, man, there'll be 20-year-olds listening to this, in complete disbelief with their current housing market.

Speaker 2:Oh yeah.

Speaker 1:My son's one of them. Yeah, I was going to ask that, yeah, I mean.

Speaker 2:How do you feel about the future of your son?

Speaker 1:in that respect.

Speaker 1:Look, he lives with his mom and he's really happy. He loves living in Islington it's like you know the village that it takes to raise a kid, kind of place and he, uh, he'll, he'll, um, his life is really good, like he's happy. That's the main thing. He's really happy. He's got a great bunch of friends, um, and I just don't, I think it's just not doesn't exist anymore that you know go out and work hard and make a living in a, you know, buy a house and that's not something you kind of it's not in his DNA sort of thing. I reckon I've unstructured that from him.

Speaker 2:What do you think Australians are so attached to that dream? It's a really big part of our culture.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I think colonialism is a massive part of that. Like get in and own something you know, like be the guy that owns the place you know, and it's just not sustainable. Obviously, we've proven that.

Speaker 2:But you're not worried about your son in that respect, maybe never being able to get into the market alone, and things like that.

Speaker 1:No, he's got two parents that own properties and one day they'll die, or two days they'll die. Hopefully. It would be terrible for him if they both died on the same day. But you know what I mean. So, yeah, I think down the track he'll get into the market. I mean some of his, it's not impossible. Some of his mates have come out of high school. They're the same age as him, a couple of them. They've bought houses. He doesn't want to live, you know, like more than 500 metres away from Swingtown.

Speaker 2:It's interesting, uh, reflecting on your life, there's an element of being a misfit for a lot of that time. Would you agree with that statement?

Speaker 1:yeah, you picked up on that really quickly. Um, yeah, I. Yeah, I've always felt like I feel like I. I. Um, when I was nine months old, I rubbed some dirt into my eye and it was like a reverse superpower thing. It's like, you know, your Superman comes to Earth and he's got superpowers because he came from another place. Well, I reversed, superpowered myself and rubbed a bacteria into my eye and then took out my right eye, so it's blind. So I feel like from my very earliest cognizance that I've felt different, like day one at school was so bad that I didn't want to do day two and I walked into the principal's office in my underpants because mum couldn't get me dressed. Yeah, misfit is definitely something I relate to very, very closely.

Speaker 2:Wow, well, let's start tracking from the nine months old. That's a bit early, but yeah, I mean, how would you, if you reflect on your childhood, that time from, say, zero to ten? How would you reflect on that time? Do you have positive memories mainly, or was it a difficult?

Speaker 1:era. Yeah, mainly positive. That's a really good time frame, zero to ten because I lived in Sydney. I was born in Sydney and I was the first grandchild. So you know, middle class white Australian people my dad's the oldest son, my grandfather's the oldest son I'm the oldest son, away we go. So I was very not spoiled not spoiled, but you know there was lots of love and affection. My parents were amazing, um parents and it really I didn't, I didn't have any kind of feeling of of not belonging until the first day of school and I got really badly harassed about my eye and and it was, you know, not strong is trauma's a big word these days, but it wasn't like traumatising, but it just made me go. Why are you people such wankers?

Speaker 2:Like can we delve into it a little bit? Was it like teasing or questioning curiosity by other kids?

Speaker 1:I think all of those things. I'm sure Jim's heard this story. I did a sticker and a T-shirt for the ramp rage and I was drawing the picture and I ended up with the guy who was doing a boneless on a ramp and I ended up with the head. To do last, which I've since worked out, is a bad idea. So I drew this cold shopping bag paper bag over his head because I didn't want to stuff up the drawing, because it was way before computers. So I just spent like hours doing this drawing and I'm like drew a Coles shopping bag on his head and with one eye cut out.

Speaker 1:And when my mum saw that sticker, she's like oh, that's really weird, why did you do that?

Speaker 1:And I told her the reason, which is what I've just told you, and she said oh, there's this really weird story where when you were in primary school, you went to school on a school bus one day with a paper bag on your head because you were so with one eye cut out because the kids on the bus teased you so much about your eye and no one was.

Speaker 1:She said I don't know how many times you did it, but a lady who was a friend of ours got on the bus back when, like random skigging on school buses and that's still a thing, um, and she told mom and mom said, oh, you know, she took the bag off me and consoled me and I don't know how long that lasted, but somewhere in my subliminal memory was this. So when I showed that sticker to mom, she got kind of really upset, which is that, and um, but yeah, it must have been in there somewhere where I went to school and with a paper bag on my head, with one eye cut out because of the hassles I was getting, going to school.

Speaker 2:Did it affect your ability to learn? I'm sure it did, but can you share that with people?

Speaker 1:Oh look, doctors and optometrists you know it's not like I'm a miracle or anything, but they're really kind of confused about my capacity, because it must have been right at a time when all of the muscles and reflexes and stuff had developed and so my eye sort of still moves. I don't it's not too sort of laggy or anything like that, but I don't know any different. It's like I was nine months old. All I remember was walking into tables when I was learning to walk, just walking into the corner of tables all the time on my right hand side. I constantly went to my auntie's wedding as a page boy with this massive black eye, because I used to walk into, walk into the corner of tables all the time when I was like two and three, wow, but no, I just don't like people that say, oh, how do you drive? I don't know any different. How do you skate? I don't know any different.

Speaker 1:Interesting when I think about it, like it would obviously be better if that wasn't the case. Obviously, yeah, we could do backside airs. For a start, I was going gonna say, like you can do backside airs, I can. But I hate them because I used to hang up all the time because I'd I'd like really struggle to know when to let go. So and I've said this to jim before I once I learned india's, I never did another backside air what about like backside 50, 50s yeah, that's a sort of a feel thing and I reckon it.

Speaker 1:I reckon more than doing the trick. It messes with my style because I have to turn my head, like I can't stand up as square as I'd like to stand. Okay, so I've got to turn my head to see kind of where my board and the coping is, rather than look along the coping.

Speaker 2:So your front foot comes into view more easily.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I need to look down and see what's going on. Yeah, wow, but I think I reckon it's just a style thing more than. But academically going on, yeah, yeah, but I mean I think I reckon it's just a style thing more than but, but academically you're able to. Um, yeah, my, like, my, my good eye worked really well, my brain works really well, which is handy.

Speaker 2:You kept up yeah, I didn't have to get the concepts I was really good at school and I didn't have any trouble.

Speaker 1:I didn't like it so much particularly high school, but, um, but yeah, it was pretty smart.

Speaker 2:Yeah, like fast-forwarding to now, like what prompted you to become a teacher.

Speaker 1:I met a guy who was just trying to be a primary school teacher and he said, oh, you know, they're looking for that cliche, oh, they're looking for blokes to teach in primary schools. And I'm like, okay, well, I'm sick of doing what I'm doing, so I'll do that. And I also. My son was about to start school and I just thought the best way I can help him do what he has to do is be there on the inside and know what they're doing and know what they're not doing and help him. You know, yeah, that was my biggest motivation. That's so fucking rad. Yeah, it worked out pretty good, dude.

Speaker 2:That's sort of like a rad dad move.

Speaker 1:Well, you know you get. It's a good job, the conditions are good, so it's a tough job but it really paid off. Like having school holidays with your kid for their whole life is the best thing you can possibly do you know, it's not like, oh, where are we going to send the kid? You know you're just with him all the time and, yeah, made our relationship really much stronger. I think that I had all those holidays with him yeah, right.

Speaker 1:Did you go straight from high school to university and then teaching, or did you have like a period of no, I, I went, I I dropped, dropped out of high school like I sort of got kicked out of high school in year 11 and um, famously my mom and dad just see it so differently to me, but I famously went away for a little while with gary now, and up the coast skating, um, up up to the Gold Coast, which was like the best possible thing you can do for your skateboarding is to go skateboard every day in heaps of different terrain with one of the best transition skaters the country's ever had. Like old school and he's a great guy too we surfed and skated and hung out. Would I have been 18? I don't think I would have been 18. He was like 23 or 24.

Speaker 1:My parents just flat out said no and I said, well, I kind of got my own money and I'm not at school and this is what I want to do. And I remember very clearly my dad saying very quietly to me I don't want you to do this, but I understand that I can't stop you doing it. And it was so. It was like a real moment. It's like oh, okay, cool, okay, well, that's what I'm gonna do. Then off I went, um, so I, I went back to high school, to another high school, um, and did year 11 and 12 and then came down here to go to uni in 1985 so that was Coffs Harbour that you were in prior to coming to Newcastle.

Speaker 3:Yeah, and what age did you move to Coffs Harbour from Sydney?

Speaker 1:I think nine, I think it was 74. I was turning 10.

Speaker 3:And so did you start skateboarding in Coffs Harbour. I did, yeah, okay.

Speaker 1:Yeah, not heaps. Long after we moved there, we used to go because my grandparents lived in Sydney. We used to go because my grandparents lived in Sydney. We used to come back down all the time and my brother and I found these two skateboards of my uncle's in my grandfather's shed and they were just like literally Stone Age skateboards. They were just so old, they were 50s what they call clay wheels. They weren't.

Speaker 2:I was going to say I think right. Yeah, they weren't clay wheels, but that's what they call clay wheels. They weren't. Yeah, they weren't clay wheels, but that's what they called clay wheels.

Speaker 1:They weren't urethane. I don't even think urethane was invented. Then when I found them yeah, it was like it would have been. Oh, I suppose urethane was early, wasn't it like 76, I think? Was mainstream urethane, but yeah, these were from the late 50s, early 60s, these skateboards.

Speaker 2:And these were from the late 50s, early 60s, these skateboards and what was the vibe like in Coffs? Was it just like surfers wanting to cruise around on skateboards to get to the beach and things like that?

Speaker 1:There was a slightly older generation that were maybe two years older than us. That were like the first wave guys like Bane, superflex, surfy, you know driveway guys, and we came in sort of on the back of them, stopping so that we'd seen guys on skateboards. But by the time we were skating there wasn't anyone on a skateboard in Coffs Harbour and, yeah, my brother and I just jumped on it really quickly. After we found those skateboards and my dad bought us, we actually came down here to Ray Richards, bought a couple of like Bain-ish you know how they used to make their own decks in there and they just they were the raddest boards but they had, you know, the Chicago trucks and Cadillac wheels and open bearings and the whole on these Ray Richards Bain Superflex copy decks. We had a couple of those.

Speaker 1:And then I started getting skateboard magazines. My dad was the coolest thing. I can't even imagine Like he worked for what was Child Welfare then DOCS, dcj. Now he worked for them for his whole life and it's not like we didn't have any money inverted commas. So for him to just go and splurge on these skateboards for us was amazing. And then he said you can get two magazines a month from the newsagents on an account. It's just like ka-ching, it's like the weirdest thing. And yes, I was just into skateboards. I think Skateboarder magazine my first copy was 1978.

Speaker 2:Wow, just for context, how old were you? Roughly.

Speaker 1:So 13. 13. 13 in 78,. Yeah, wow, is that right.

Speaker 3:Yes, that's right. Do you think he saw the value? You said before that you, you know you felt like a misfit from a young age do you think he saw the value in you finding something that like, almost was meant to be and that, and that's why he was so supportive and that's why you know he wanted you to have the magazines as well, to kind of have access to that subculture it's really hard for me to objectively say that now.

Speaker 1:I answer that objectively because I feel like that must have been it. He's an amazing guy. He's way more intuitive than he's expressive, so I think maybe he just went okay, well, you're into this stuff. You're buying them anyway. It's costing you your paper-run money. Stuff. You're buying them anyway. It's costing you your paper run money. Everyone can, everyone benefits if I just sort it out at the end of the month. Um, but yeah, like supportive is a key word. He was just absolutely incredible for um, for my skateboarding he used to. He'd take um, take my brother and I. Well, yeah, I mean we'd all go to sydney, obviously on family trips, but he'd take my brother and I after my grandmother died. Um, he'd just chuck us in the car on friday night, drive us to sydney. He'd. He'd go and see my grandfather and check on him and we'd just go skate north, ride the whole weekend, get back in the car sunday, I'd go home. It gets like a 10 hour drive. I reckon it would have been back then Surely Easily.

Speaker 2:Yeah, 10 hours. Yeah, there's no mega freeway.

Speaker 1:No, you had the freeway, hawkesbury River and that sort of thing, but everything else was just the Pacific High, yeah, and he used to. Every weekend he'd take us up to this really horrible little dish bowl up at Junction Hill near Grafton, and just me and my mates, and on a Sunday I'd go off to church, come back, say do you want to go up to Grafton? Yeah, sure, we'd rally a couple of mates and he'd drive us up there. That was sort of an hour and a half. We'd sit in the car and read the Herald, take some pictures, get back in the car at four in the hour, drive us home again. Wow, it's insane.

Speaker 2:You pictures get back in the car at four and they drive us home again. It's insane. You just triggered a memory. Actually, I remember my mom it's like 19, 1989 so and uh, there was a demo on at fairfield mini ramps. It was the vert ramp in the mini ramps.

Speaker 2:You probably remember those and I remember like all my friends caught the train up but I missed the train to go with them and I remember she drove me from Nowra and at the time it was like almost three hours, you know and just drove me all the way to Fairfield. And I got there and I'm like, oh, I'm kind of embarrassed, you're here, mum right. And she's like, okay, like I'll just leave you then, and then left me with my friends so I could catch the train back with them, and then she just drove all the way back. So she just did like six hours, just three hours, and then turned straight around. I get a little emotional actually, yeah.

Speaker 1:I know I feel like, if you've been parented like that, it just is a blueprint for getting it right. It really is like it's good to hear.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I feel like that. It's just like I was. There was so much support and love and just a feeling of family in our house and my dad and mum are both really into family and I think that just sets you up for really ingraining that. It's not like a conscious thing thing, but you just know how important it is when you bring your own kids up that they've got that connection you?

Speaker 3:you mentioned your brother earlier. Um how much younger is he than you?

Speaker 3:uh about 18 months now in a lot of stories when I ask you a lot of questions when we're hanging out, you often reference your brother. He seems like he's a really big and important part of your childhood and kind of like I don't know skateboarding for you as well. Do you think that bond was made tighter as well? I know I don't want to keep kind of going back to that misfit thing that you're talking about, but if you were having a hard time at school and you did feel like you weren't fitting in you're talking about, but if you were having a hard time at school and you did feel like you weren't fitting in, and particularly with skateboarding not being the most popular thing in the world during that period too, do you think that made yours and your brother's bond maybe stronger as well?

Speaker 1:yeah, we had, um, we had this ditch that we used to skate over on the pacific highway and it was like a, it was just like a drain. Uh, we called it the drain and it was next to this, next to the service station. It was about it's probably about four foot deep. It was just, it was like a beautiful, like you, just it's. It was stupid. When we found it, we're like this is insane, it's like your own skate park, it actually. It had different types of surfaces, it had obstacles, it was smooth, it had a tiny little curve at the bottom where it met the flat bottom. The flat bottom wasn't dead flat, so you could sort of pump through it. It was insane.

Speaker 1:And we skated that like every day for years until the skate park in Coffs Harbour was built, which was I don't know nine or 80 or something like that, and my brother and I like we'd come home, get on our bikes or we'd just run from our place to this ditch and we'd just session it. He sent me some photos of it, of our like little crew the other day doing this like it's like Charlie's Angels thing. We're all like standing on our tails, peace signs, you know really bad scoops and Captain Lightfoot shoes. It was a, anyway, but yeah, I think that that thing that we did because he played rugby league he was really like he was. I wouldn't say I was jealous of him because he was batshit crazy, but he just looked. My partner saw a photo of him the other day and she goes oh okay, now I get it Like. He looks like a freaking movie star. What?

Speaker 2:do you mean movie star?

Speaker 1:Well, he looks like Robert Redford. He's a hunk. Yeah, he was like gorgeous the cheeks, oh beautiful. Like one of my 57,000 girlfriends over the years, like this girl I went out with first time she met him. She's like this is like roundabout Thelma and Louise. She's like looks like Brad Pitt, it's like, and he does. That's it Robert Redford, brad Pitt, you know. Blue eyes, surfy hair, great cheekbones I was so jealous of that stuff. And he played rugby league, so we didn't. I played football, he played rugby league, so we didn't, I played football, he played rugby league. I wasn't allowed to play rugby league, thank goodness, because of my eye. My dad was really concerned about that. So I grew up playing football and he played rugby league, so we didn't have that connection. But once we started surfing and skating, we did that stuff right through, like probably separated a little bit, early high school. But in the late primary school, early high school days, we were just inseparable on skateboards and surfboards. Yeah, that's so cool man.

Speaker 2:Yeah.

Speaker 1:And he's still like. He's still like we communicate almost every day over the interweb and he lives in New Zealand. Yeah, he's just. We can get on the phone and just be like pissing ourselves, laughing almost immediately from you know, just because we have this kind of shared language that we grew up with.

Speaker 2:Oh, there's something to be said for that.

Speaker 1:Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 2:Like is he still good looking?

Speaker 1:Well, I don't know how to answer that question's. Uh, he's, okay, I'll reframe it are you still jealous of his looks not jealous of his looks.

Speaker 1:He's currently running this um thing. He sent a picture. He sent a picture the other day where he's at his hair. He goes to his hairdresser he lives on, he lives on the west coast but his hairdresser's on the east coast so he goes over to see his kids, goes and gets his hair cut, does all these sort of business, and, um, he sends a picture of him getting his hair cut and I'm like I'm just replied. He missed a bit. He's growing this massive like mullet thing off the back of his head but the front of his bald, so all the front of his head's all shaved and he's just got this like cat sitting on the back.

Speaker 2:Oh, really like a legit mullet it's so funny.

Speaker 1:So, yeah, I know I'm not gonna, I'm not throwing myself under that bus I love him to bits.

Speaker 2:You win, man.

Speaker 3:You win the good looks competition did he did, he keep skating, he still has. He got older. Yeah, he still skates.

Speaker 1:He throws himself around Like he. There's, like you know, new Zealand, like there's parks everywhere. He used to skate in Christchurch a bit. He'll always send me a video if he goes skating. But he's still got a board. It's probably still the same board. He's probably still got that old fart board. I'm not saying, oh right, yeah, got that, um old fart board. I'm not saying, all right, yeah. I'm not saying he definitely still has that board. He might, might be one of the other ones I sent him. But he, yeah, he's still got all the boards he rides are just boards that I give him, that he's, and he keeps them for decades, right so.

Speaker 2:So if we just sort of track the chronology a little bit, if you don't mind I always like to do that, just to put things in context so obviously you found these like surfy skatey boards that may or may not have clay wheels, like, and then you found more rideable boards, the bane boards, did you say?

Speaker 1:well, they were like that.

Speaker 2:Yeah, we got these ones from ray richards that were like bane superflex okay, basically that fiberglass, whatever that is five so you could actually, like you could, could turn them. They rolled better.

Speaker 1:Yeah, it had urethane wheels, Urethane wheels, okay, yeah, yeah.

Speaker 2:So when was the first time you got like a proper, like, I guess, more modern day skateboard that was, you know, usable on ramps and transition?

Speaker 1:Or the ditch yeah in my. It's just so funny when you think about it. Yeah, I know, I do remember. When you think about this stuff, it's just so weird. It's like my friends. We had a sporting supply shop in Coffs Harbour. It's the only place you could get skateboards and the only skateboards you could get were Edwards DHD. And my friends got together for probably my 13th birthday and threw in and got me one of those DHD, like you know, the taper kit kind of looking thing with the stringers through it. Yeah, right.

Speaker 1:I think actually it was just DHD and they got me one of those and I had like Edwards trucks and some Aussie wheels and that was the first like like this is like I can drive over anything on this thing. It was the best you know getting off a fiberglass board with open bearings onto one of those. It was just like.

Speaker 2:Where were you skating at?

Speaker 1:In the drain, in the ditch, in the ditch, and we lived across the road from a Catholic school and they had this really cool driveway. There was a church up the road that had another really cool, like, really cool driveway. There's a church up the road that had another really cool, like, really steep driveway that went out onto this horrible, horrible road called valley street that we used to bomb and it was just most of my brother just like annihilated himself on that one day, like skinned himself, um, but yeah, you'd say you'd, you'd skate this driveway and and it was really good to to learn like tight control because if you, if you like, didn didn't hit a turn or you know, you came out of there a little bit too straight, you were out on Valley Street going faster than you wanted to be on an inappropriate skateboard and you didn't last long. If you made it to the grass, you were really really lucky. But yeah, driveways, the ditch was amazing. I feel like we just learned to skate in that ditch because, like, kick turns.

Speaker 2:That's exactly what John Gray said. Yeah, you know like where were you getting your inspo from Well?

Speaker 1:I don't want to jump on Johnny's coattails, as fancy as they are, but it was the same sort of thing Like it wasn't until I.

Speaker 2:So you're saying you did the first kick turn in the world. I'm telling you right now yeah. Yeah 100%.

Speaker 1:No, it was only when I listened to that, to Johnny saying that I'm like, yeah, how the hell did we know what to do, Like you get to the top of the thing? I reflected on it, thinking it must have been a surfing influence, because we surfed and we saw people surfing all the time. You get to the top of the wave, you turn around and come back down. You get to the bottom of the wave, you carve off the bottom, you go back up. I'm guessing that's how we knew what to do.

Speaker 2:That's it, yeah, and if you've never seen it done before, technically it's an NBD.

Speaker 1:You're right and it had never even occurred to me before until I listened to John say that the other day and I'm like, yeah, that's mental, like I used to ollie up onto this PMG box like street, ollie out of the ditch onto a PMG box and do a oh, like a Telstra box.

Speaker 2:Oh, okay, sorry. Like an electrical box.

Speaker 1:Yeah, it's like that. Sorry, I should have said Telstra box. And it sat up one end of the drain and it was probably you know that high I'm putting my hands up to show 30 centimetres out of the drain, up near the top. And so if you clipped your tail going up the bank, you'd land on a rock and roll on top of this box and rock back in. And so I invented street ollies and street rock and rolls when I was 13.

Speaker 2:That's insane.

Speaker 1:Well, I wanted to do a rock and roll. It was the only place in the ditch that you could rock your board out.

Speaker 2:But you'd heard of it or you'd seen it. No, I'd seen pictures of rock and rolls. You'd seen a picture of rock and roll. Yeah, yeah, yeah. So you just improvised it.

Speaker 1:Yeah, because I was like probably two years into Skateboarder magazine by then.

Speaker 1:so I was like you know, doug Saladino and Board Slides were already a thing. Eddie Gilker is doing Frontside Rocks already, you know. So I knew what a rock and roll looked like in a still photo. But yeah, so you just like clip your tail going up the wall, land on top of this box, do a rock and roll, rock back in, shuffle, you know, shuffle your feet, shoulder charges bottom 57 000 times on your way. But that, yeah, it was just when I thought about um, when I thought about what john said the other day. I'm like, yep, that's really really weird. How did we know what to do? You just improvise, you adapt.

Speaker 1:Your terrain is what it is and that's skateboarding. It's always been skateboarding. Your terrain is what it is Like. It's hard for kids, young people, even you kids, to understand. He says, looking at Jim, I'm 41. Yeah, it's hard to understand. Yeah, right, so it's hard to understand, yeah, right. So it's hard to understand that skateboarding was just skateboarding, like it didn't have subgroups or it was just skateboarding. You had a skateboard and you were a skateboarder. And if you rode to the shops, if you rode in a ditch, if you rode on a ramp or whatever it was, you were just skateboarding, and that's how I grew up.

Speaker 2:Wow, that creativity man. You know where else in your life has it been manifested? Or whatever it was. You were just skateboarding and that's how I grew up. Wow, that creativity man. You know where else in your life has it been manifested? Sorry, jim, you were going to say something. Yeah, look, I mean, it nurtures creativity. You know, it really did Like I want to do this, I've got to improvise this and whatever. So where else in your life has that creativity manifested?

Speaker 1:Absolutely everywhere. It gives an example. Life has that creativity manifested absolutely everywhere it's, and I feel this is why it started. Um well, you like, again, through skateboarder magazine 79, 80, the punk thing started to happen. And so you had the santa cruz guys, like olsen, um duane, pet Alba, those guys you know slightly later, like all the Bones Brigade guys not so much Tommy Guerrero, probably, but you know, cab Hawk Hawk's got exactly the same taste in music as me. All those guys were into punk and it just I found that through Skateboarder magazine and I'd watch Olsen and Dwayne Peters particularly just build their own, do their own thing, do their own shit, and I started making shirts and doing things to my shoes.

Speaker 1:I wasn't really allowed to do too much with my hair, which is a shame. I got right into that when I came to newcastle, when I went to uni, I was getting, I just like dyed it and got my war semi immediately. But yeah, I reckon it was just. I think it was in me and it just needed some sort of little flame to flicker and go you, this is your thing, you can do this. This is these people and I was. I don't remember ever. I don't remember ever getting really badly hassled apart from the cops one night in Coffs Harbour. But when I was growing up, when I first started doing my own sort of punk thing I mean it was a pretty piss-weak version, but I don't remember really getting hassled. I was just Sean the skateboarder who did his own thing and wore weird clothes and like I'd wear pyjama skating and odd socks. You know it sounds so weird and like so watered down now, but in Coffs Harbour in 1978, you know a guy with half a pyjama shirt, screen printed with checkers and the back of it saying Devo, and odd socks, and you know they would have been like what is going on here? Where is our world going? What's going to happen with the youth?

Speaker 1:You know, and I had a very, very close, who's still a very close friend I call her my oldest friend. I don't mean that she's older, but my mum's best friend's daughter and she was really into music and really into punk and I'd go to Sydney and hang out with her. It was so random, I don't know why my parents let me do it, but I'd go to Sydney and just stay with her and her dad for like a week and we were like 15 years old going to pubs in Neutral Bay in Mossman watching punk music. Like first band I ever saw was Tex Deadly and the Dum Dums, which was Tex Perkins and half of the Johnnies in a pub in Mossman.

Speaker 1:Actually, my brother was there that night and we all got in, we were all dressed up and he was like surfy and he looked about 12 because he was about 12 and they said you guys are fine, he can't come in. Oh, can we get him something to drink? Sure, you can get him something to drink, but he has to drink outside. He's probably 14. We would have been nearly 16, I reckon, but yeah, and so I just sort of got into that feeling of being connected to that punk world that I saw in the skateboard magazines Dude this is interesting.

Speaker 2:How old were you when you? What was your first band you played in?

Speaker 1:First band I played in was called the Boneless Ones, with my mate, mike Cosatini, and his brother Paul, and they had a mate called Wayne who lived in their street, so they were like this three-piece that played U2 songs quite well actually, considering their age, and they just wanted someone to be a singer. And Cos said oh you know, why don't you be a singer? You can be the front guy. Surely I couldn't sing for shit, like actually, but I could front man. Once I got over that feeling of holy shit, this is terrifying, the first, I reckon, three gigs I did, which were all in just now house in Cameron Street in Hamilton. I wore this like camouflage mesh hat thing like Mick Jones wears in the Rock, the Casbah clip, and that was just so that I was like, so no one could see how extremely terrified I was. Dude, that was the boneless one. That was like 1985 85.

Speaker 1:Wow, like as a front man and yet who felt like they couldn't sing oh no, I can't sing like I still sing it must have improved over the years I reckon probably, um yeah, oh yes, I I'm sure I did Like, yes, I'm sure I've improved. I think about what I'm doing now, whereas before it was just a performance and it was like didn't really matter so much what I was singing.

Speaker 2:You're screaming a lot A lot of screaming.

Speaker 1:Yeah, yeah, the next band we're. So that band that I was in called the Boneless Ones. They transitioned into a band called Bark and it was the same three guys and they had a guy called Carl Richardson who sang like incredibly, like really he was even more terrified of singing than me. They'd organise busking gigs Just him and Mike would go and busk to build up his confidence and he wouldn't even show up at that. But they turned into quite a successful like Newcastle 80s band. They had a few singles and stuff, dude, yeah. And then Cos got me into this sort of little unit he was working with some guys from high school called Dissection Committee and I was in that band for I don know, maybe three or four years.

Speaker 3:Yeah, rad yeah, that was sick. Had some interviews in skateboarding magazines as dissection committee apparently yeah yeah, what do you mean?

Speaker 1:apparently, well, jim jim said, no, I'm straight edge man are you really no?

Speaker 2:no, I mean I've got the physical evidence of these interviews yeah, if jim says it's there, it's like, but you just don't remember.

Speaker 1:No, I do.

Speaker 3:He just keeps telling me this stuff and I go oh really, okay, if you say so, he plays it. He's too chilled out, he doesn't want to play into his own mythos Interesting, so I've got to do it for him.

Speaker 2:That's why we need you, Jim.

Speaker 3:That's Jim. That's why we need Jim Mythos. Is that something you like order? Is that food? Yeah, it's kind of kebab, great question.

Speaker 2:Actually, how did you two meet?

Speaker 3:Can I go back to before we met right?

Speaker 2:Yeah.

Speaker 3:At Newcastle Skate Park when the halfpipe went in in 1996. It was that ramp. I don't know if you ever saw it. The flat bottom wasn't very long For its height. The one on the beach, yeah.

Speaker 2:Yeah, I remember it.

Speaker 3:The ratio of transition to flat bottom. You know it's kind of scary to skate. So it was a short flat bottom. Yeah yeah, it was really fast, especially when it had the original like coating on it before it had various surfaces.

Speaker 3:But, um, I would have been in year eight and, uh, this guy turned up that my friends and I would call undie head and undie head. We thought undie head was like like now, this wasn't a diss, we thought he was really cool, but we also thought he was a little bit unapproachable and we thought he was like 40 or something, he was probably 28. But it was just that age thing back then. So you know, I remember this guy at the skate park telling me he was 23 and I was thinking, wow, how can this guy skate Like an old man? Yeah, but this guy turned up in a bandana kind of like, maybe just like a tank top, not dressed full 80s like not mid-80s, maybe 1990, punk look and he was just ripping that ramp, skating super fast, and we'd just be skating the ledge or something like or the wedge or something at the newcastle park and uh, we'd say, oh, undie Head's up on the ramp, let's go watch. And it was Sean.

Speaker 3:But I didn't know Sean had been a sponsored skateboarder. We knew some of his friends had been, so Anthony Simmons, for example. Simo, he used to work at PD's Pacific Dreams, a surf shop, and we all kind of knew that he used to get stuff from like Cooter Lions and Universal and things. So we kind of knew that he used to get stuff from like um, cooter lions and universal and things. So we kind of assumed that sean had that background. But we didn't know because of the people he was with. But a lot of the time he was also by himself. Um, but there was kind of a bit of yeah, myth about under your head and um, because the bandana, the bandana looked like he had no one wore. In 1996 no one was wearing a bandana. This is is before the Tony Trujillo thing of like the early 2000s, yeah.

Speaker 2:Well, he wore more like a headband, but I know like the look With a pulled back, with a pulled back Almost like Peter Andre would have been running at the time, kind of thing. Yeah, like a pirate vibe.

Speaker 3:Yeah, yeah, he's getting a photo. I love it, and I think it was even the same pattern as the undies.

Speaker 2:Like you know, the Can I just clarify you weren't saying this to his face because you were scared. No, no, no, no.

Speaker 3:You were low-key, scared of him as well. Not scared in, like as in. He seemed scary, as in.

Speaker 2:Oh, that's a sick. Look, that's a sick photo.

Speaker 3:Yeah, totally, he looked like he rode for Alva.

Speaker 2:Yeah, he does Totally. He looked like he rode for Alva. Yeah, he does. Like actually that photo, he kind of looks like a slightly taller Alva.

Speaker 3:And like that's what we would even say. We would be like man. I wonder if that guy like rode for Alva or something back in the day you know, back in the day would have been four years beforehand as well, but time seemed a lot like a lot longer back then.

Speaker 2:I want that photo.

Speaker 3:So fast forward into the 2000s and we used some older guys started coming and setting up like slalom, like cones, and I don't mean like as in just mucking around, like learning how to do really good slalom, as in like good style, being able to pump from the hips, building momentum like what tic-tac is supposed to be, but not when little kids do it Without ticking or tacking, just carving it.

Speaker 3:Just generating speed from your hips, essentially, and going really fast and good tight turns. And one of them was Sean and we started. I put two and two together Like that's honey, honey, honey, honey, honey, still skating, still ripping. This is now like 10 years later, but it seems like you know, it seems like 20 years.

Speaker 2:Honey, it's back. What Honey? It is back and you've been in contact for 10,.

Speaker 3:You'd Seems like 20 years. So what have you been? Aunty had his back. What Aunty had his back?

Speaker 2:And you've been in contact for 10. You'd seen him around for 10 years Before you actually met, but I hadn't made contact.

Speaker 3:Alright, even then I said hello to him a couple of times, but not proper contact. Yeah, then I started when I started working at a library. This woman, lisa, who's a really good friend of mine, that I worked with and she's Sean's age, her and her husband were friends with Sean and she said my friend Sean used to be a sponsored skateboarder. Now I was in my mid-20s at this stage and he's my age and I straight away knew who she was talking about, because by then I'd figured out that his name was Sean, I'd figured out that he had been sponsored and all that stuff. I'd done a bit of stalking and yeah, and then I think, did she? I don't know, I think she said something to you, maybe that she worked with a guy that was a skateboarder, but somehow then the next time we saw each other I think I just started talking to you, right.

Speaker 1:No, I already had a crush on you talking to you, right?

Speaker 3:I already had a crush on you. Oh, yeah, for sure, because I, yeah, I know, I just saw all these things just happen and then so one day, we just started talking right.

Speaker 1:Yeah, like it was like I think that was. That was um kind of around about the time I started going out with my lisa yeah, with also also a very good friend of yours. Yeah, yeah, yeah. And I think that connection was I'd be like oh, that guy's so cool, I love that guy. She goes oh, barney, and I'm like what, you know, that guy, yeah that's right.

Speaker 1:Yeah, yeah, barney. And I'm like why do you call him Barney, isn't his name Jim? And he's like, yeah, blah, blah, blah, barney, rubblehat, yep, and yeah, very, very soon sitting in Suspension one day before it was called Slingtown. Let's cut to the chase.

Speaker 2:Suspension, suspension Cafe. Okay, and now it's called Slingtown, all right, just for those that aren't familiar.

Speaker 1:Yeah yeah, and you guys were all sitting in the window with Marcel and there was you and Nash, and you were the ones I remember and a couple of other guys, your guys sitting at the front like shooting the shit, laughing, just covered in tattoos, and I just said to Marcel, that's the cool crew, those are the cool guys I wish. No, you guys are. But he said, oh, do you know them? I said, oh, I know that guy because I knew Nash, because he was Jeffrey and Lisa, anyway, blah, blah. But I said I want to know Jim. He's like the coolest guy, he's so funny, jim, that is not true Anyway so anyway, then one day we started talking.

Speaker 3:Yeah, I think we got numbers and we met up for like a date. We went and hung out.

Speaker 2:We went to a suspension and had a coffee.

Speaker 3:But I can remember one day seeing you, not a beer, no, I went and had a coffee. It was really civilized, but yeah, we went and had a.

Speaker 2:It's the first time anyone's ever done a sound effect on this podcast. That's right.

Speaker 3:He's creative, so you asked him about that before.

Speaker 2:I can tell man it's manifesting everywhere.

Speaker 3:But I'll tell you this and we need to go back to Sean, but I will tell you this that I remember, when I became friends with him, messaging one of my friends in Sydney that I grew up skating with and saying you'll never guess who I went and hung out with today. And I said I went and hung out with Andy Head. Andy Head, his real name's Sean.

Speaker 2:Is it his real name or is it something else?

Speaker 3:It could be Gravel Burns and I said, yeah, and I had all this inside goss. You know, I confirmed heaps of things. I was like, yeah, he was getting stuff from like Universal for a while and I could kind of confirm all these things. He was running for PDs and I think he was getting Aussie boards at one stage, like really early on, and I could confirm all these things that we'd I kind of hypothesized, we'd made up a little bit of a lore about him because the other guys we knew because they'd been around, like Simo and then John Bogarts I suppose was part of their crew All those guys kind of had Sean had been in magazines a lot as well during the 80s as well, but I suppose people remembered John's board or Simo worked at the surf shop.

Speaker 3:So people kind of knew a bit of his lore like L-O-R-E. But Sean was a bit more mysterious In the early 90s too. I think he'd been in the UK for a while. So when we all came on the scene he wasn't there as much, whereas we knew who Bogarts was, we knew who Kenny Gibbons was, we knew who all those guys were, whereas Sean maybe had stepped out of the spotlight for a couple of years before reappearing as Undie Head.

Speaker 2:Undie Head.

Speaker 3:In my mind.

Speaker 2:How do you feel about Undie that?

Speaker 3:name. There's only four people that call him. That probably like not.

Speaker 1:One of those people now is like a 12-year-old girl. Hey, undie Head, it's so cute, no when he first told me. I'm like, oh, and he goes. No, no, we meant it like respectfully and affectionately. It's like, yeah, I get it like. Whatever, I was a person with a mythos called underhead. We're like how cool is that? Guys, younger skaters look at you and go well, where is that guy from? Man, look at that guy. He's underhead. He just comes out of nowhere and then goes as quick as he can.

Speaker 1:You know how funny is that?

Speaker 3:I thought he was Spanish or something for real because his hair was so jet black as well. I was like can he even speak English?

Speaker 1:Yeah, I practice my words.

Speaker 2:Yeah, it was like. I mean, yeah, that photo, like it was a lot darker, surprisingly.

Speaker 1:That's crazy. Surprisingly, 30 years ago, how much darker was it?

Speaker 3:But he did. He looked like he rode for Alba or something. I think that's the best context to put it so sick.

Speaker 2:Yeah, when skating started to get a bit more serious, like you got out of the ditch and started skating ramps, where was your first actual ramp? You skated?

Speaker 1:Do you remember that day we used to go to again?

Speaker 1:my dad would take us to Sydney and we skated Skate City, which is just like it just blew my mind when was that that was at Manly Okay, and it was all the fiberglass Wazmel stuff, the two quarters, the bowl and the half pipe, and nothing had flat bottom. Well, there was flat bottom between the quarter pipes but they were offset. They were like a weird unit. They weren't like a half pipe, they were two quarter pipes that were at weird angles and it was right in the walkway so you couldn't really get anything going. But anyway, and I was like 13 or 12 or something, but that was in magazines like Wedge and Adrian Jones, johnny McGrath, they were there all the time. I don't remember ever going there and not seeing if not all three of those guys. If I was there on the weekend, at least one of them. I mean.

Speaker 1:Sure, speaking of law, I'm sure Johnny McGrath lived underneath the halfpipe for a while or under the bowl. I'm sure Wedge has told me that and he was like 16. He just hitchhiked with Wedge, just jumped in wedge's car. Basically wedge says, oh, skateboarding's happening in sydney, not melbourne, uh, so I'm gonna move to sydney. And johnny's like, yeah, cool, uh, hang on, I'll just get my bag. And they just jumped in. He just jumped in, he, he's like a kid, it's like I'm sure that's like you'll go into jail these days if something like that happens in your life. So raw, yeah, really, really cool. But Wedge is like if you're going to jump in anyone's car, he's the guy you know, he's just so sensible and intelligent, and not to mention like Wedge.

Speaker 1:I've said this to people over the years Wedge and Adrian and Johnny are like the holy trinity not that I'm religious, but the holy trinity of Australian skateboarding. They're the people that I remember being the guys.

Speaker 2:Because that was one of my questions, like who were some crew back then that were just, you know, the ones that were blowing your mind and you were looking up to? So it was those.

Speaker 1:Well, because I lived in Coffs Harbour, the ones that were blowing your mind and you were looking up to. So it was those.

Speaker 2:Well, because I lived in Coffs Harbour the only guys I saw were in the magazines, and that was those three guys.

Speaker 1:Yeah, like that, like AJ, johnny and yeah Well, adrian Ariel Jones and Wedge Francis and Johnny McGrath, and there's just classic photos etched into my brain of those guys skating, like Johnny's tail tap with his hair flying over at Albany, and Wedge just frontside airing across the bowl in Manly and Errol doing or Biff, even actually Biff doing backside ollies. Yeah, and like those were the guys and they were what? Are they four years older than me, ish, um, four or five years older than me, and they were just the crew like, and some of them were assholes, like I'm not not throwing, I'm not gonna throw fox under the bus, but john fox, yeah but some of them were just under the bus yeah, some of them were, um, that were just so nasty to the little kid, like I was just a little kid, I was like 12 or 13.

Speaker 1:I just wanted to skate and you just couldn't get a go. And then Wedger would just sort of say, oh, you want to go, kid? Yeah, yeah, thanks. And then he'd just stand in the way while you rolled into the halfpipe.

Speaker 2:But, dude, I still think there's something to be said for that grom abuse Like I sustained it as well. I remember turning up to Alloa Bowl and I was like 11 and getting. And I was tiny when I was 11. I'm still a short guy and I got some dude just yell, screaming get off the fucking island. And then some dude was calling me a slimer. He's like get off the island, you slimer. And all these years later I still remember it clear as day. But I swear it builds resilience. I feel like kids are too soft these days. Well, yeah soft.

Speaker 1:Maybe adult or more adult-y people are a little bit more respectful, I don't know. But yeah, absolutely Didn't do me any harm at all because they were gods you know, like you, don't get in front of them. You don't ride there Exactly, you know you earn that go.

Speaker 2:Now we get yawed up by scooters to get out of the way.

Speaker 1:Were you on your DHD, then no, I was really lucky around about that time. My DHD broke. It was sad, but it must have been like it would have been a birthday of christmas, probably birthday and um my, my dhd broke. So dad took me to um skateboard world in burwood and adrian was there. So that was like god. I walked up and adrian jones is like he's just a kid. What was? He would have been 17 years old or something like, maybe not even, but he was Adrian Jones. The magazines were already calling him Adrian Ariel Jones and I'd seen him skating at Skate City and he just happened to be the guy that served me and he sold me my first American Pro deck, which was a Santa Cruz cruz red dot steve olsen, which is just the most like it was. Like the fact that it was just sitting on the wall was too crazy. Like how is that just sitting on the wall? That's like it's life-size, it's made of wood. What's what's going? What weird world this is. And that was your dream board oh so my dream board?

Speaker 1:yeah, like I would have if, if I'd have mean, I went in just wanting a skateboard, yeah. So, but the fact that that board was there on the wall and I could just say, can I get that one, can I actually get that? Can you get that skateboard down and I buy it and take it home and yeah.

Speaker 3:Would he have been writing for Ace at the time?

Speaker 1:Yeah, jim, I guess. Skateboard world, yeah, I actually don't know. You would know better than me. You've trailed the magazine world.

Speaker 3:I was just wondering if you know if there was any kind of temptation to buy something local.

Speaker 1:Oh, yeah, I know what you mean.

Speaker 3:Yeah, and the DHT too, I did.

Speaker 1:He, I think, because the deck would have cost I don't know like a lot of money. He steered me towards ramp rippers which were DHT pink, which was fine. Pink was punk, yeah. And Errol said, oh, these are a bit cheaper and they're really good wheels. So he steered me towards those and they were really good wheels, like great quality urethane. It lasted forever. I've still got them, but they lasted forever. They were really good wheels. But yeah, like, all that product and who wrote all of that stuff was just beyond me. You know, like even I didn't really even pay attention in the magazines who's who was like obviously alva rode for alva and the santa cruz guys were my santa. You know they were the punk guys, but it was just was more about the. It was more about the, the type of skater you wanted to be. You know, like if you you weren't going to ride, even even back then I wasn't going to get a veriflex deck yeah, that was a tribal thing too, wasn't it kind of was?

Speaker 2:yeah yeah, yeah, like which tribe you align? With yeah, it's interesting. You mentioned john fox's name, which to me is a very interesting character in australian skate history because he was the editor of a very prolific magazine, skate and Life. Back in the day. Did you have a building desire to get in that magazine and be on the right side of him?

Speaker 1:I was always on the right side of Fox, apart from when the punk element design, the Ped Boys, were at Skate City. Yeah, that was like, and it was just them being punk. Yeah, you know, if you just like it's, dissing little kids is the same as spitting at a band. You know it's just sort of pointless and dumb, but it's what you did. But I never, ever had a problem with Fox. He was a rad guy right through the 80s and 90s and when I sort of used to see him at Bondi in the Bola Rama days, he's a really, really nice guy. Yeah, that's why I said I'm just taking the piss. They were just narky. You know, punk kids just marking their territory.

Speaker 2:But it was also very reflective of Australian society and culture in that time. Anyway, I just think it was translated in skateboarding it was happening in the surf. It was happening at the footy ground. Yeah, I don't know. Would you agree?

Speaker 1:yeah, absolutely, and I, like I said before, I've I've always felt like wary of that sort of thing. You know what sort of thing, you know what sort of thing, just where kids are nasty and aggressive. And you know, I got, like I said, I got bullied in primary school until I got some friends. Then we moved to Coffs Harbour and the whole thing started all over again.

Speaker 2:So I was always really wary of Even being in a punk band, you didn't want to like live up to the persona of the front in a punk band.

Speaker 1:You didn't want to like live up to the persona of the front man punk. No, I, I just no. I was much more theatrical. I was more I don't know what who, like jello biafra, like you know, I'm just theatrical giving putting on a show. Not I wasn't angry or violent or I just used to like to say you know, I had a microphone and I liked to say funny things and make the crowd laugh and just entertain. It was like I wasn't an angry punk guy. It was way more theatre than that. You know, like New York Dolls or something you know it was like. Well, we did drag a bit, but way more New York dolls than exploited, if you know what I mean.

Speaker 2:Yeah, gotcha, Wow man.

Speaker 3:But by the time Skate and Life would have hit the shelves. That's 88,. You were kind of pretty well established, like you were already pretty well established in the Australian scene. Anyway, what was? If we go back a little bit, bit what was, and sorry if I keep dragging it back, but okay, I just did I. There is one thing that I wanted to bring up because it's pretty unique and it's a sign of the times and stuff too. So you started getting you're being flowed aussie boards pretty early on through tim door, is that correct?

Speaker 1:yeah, no, it's funny when I was listening again listening to john's thing the other day, um, that we so, coughs, coughs, got a commercial skate park. I was in high school, definitely in high school, maybe year eight, so say 14 um, and it had, you know, it had the Pro Shop and had higher boards and stuff. And Tim came up and stocked the Pro Shop with Aussie boards and they were our higher boards. And then he came back, I don't know some amount of time later, like later that year, with the aussie team and did a demo and that was like danny van duane, hecadar, um, chris briggs, the four of them, I can't remember who. The other one was off top anyway, but you know, danny van stuck in my mind, um, because I'm still really friends with Danny, but yeah, and then Tim, who I, you know, like I wouldn't have known Tim, he looked like a professor. He still does look a bit.

Speaker 1:Anyway, he just said to the guy because I was working at the skate shop, and he said to the guy, roger, who ran the place, he said, oh, who's your local guy? And Roger said, oh, sean's our kind kind of, he's probably the best skater here. And he said, oh, I want to hook him up with some t-shirts and and and a board and stuff and he can be like your, our advertisement for aussie, and that's so that I kind of it. Just that's just what happened and didn't really dawn on me until ages later that that was like pretty cool getting free skateboards. Like I don't know how long it lasted, but maybe you know, I got a couple of free skateboards and I wore their T-shirt and it was a nice kind of feeling of someone saying, oh yeah, sean's our best skater that kind of thing and you're sponsored now.

Speaker 2:Well, yeah, that was a big thing, man Like I'm sponsored. Everyone wanted to be sponsored, yeah.

Speaker 1:I reckon at that point I just didn't even understand the concept of that. Like it just didn't even dawn on me that that was a thing Like guys wrote for certain teams and it was more like a team thing. I just didn't really understand that that's kind of and it's not sponsored Like they gave me. Sponsored to me is you know you're getting your travel expenses paid and you're getting all your boards and you're getting all you know, you're kitted out all of that stuff. And this is like I got a couple of boards floating in a T-shirt and I had to. When I was skating I wore the T-shirt and that was like what inverted commas sponsorship looked like in whenever. That was 1980.

Speaker 2:So, like because I want to build up to, I want to slowly build up to the point where skateboarding went from vert and then vert died in the early 90s and then it became heavily street and you probably remember that big change. It's a pretty monumental change in the history of the art. What vert ramps were you mainly skating on the regular, whether it be in Sydney or Newcastle or Coffs?

Speaker 1:Yeah, when I moved, I moved down here in 85 and I met my mate Mike down at the old Bar Beach Quarter Pipe and they were about to build a ramp in this guy's backyard in cook's hill, um, and they took me he cause just took me there straight away and said, oh, this is what's happening and it's like, oh, and it's like, man, it was this funny little ramp with all just the most you know, it's like everyone's first back out half pipe was just like johnny was saying the other day, it's like you just steal whatever you could get and like I don't remember if ours had street signs on it, but it was that sort of thing. Um, but it never really got going. I don't even remember, I don't even think it ever got skated. It's just one of those like a pipe dream.

Speaker 1:But then, um, the there was this east, that 80, 1985, there was like an Easter get-together at Port Macquarie, peppermint Park and I didn't go because I went back to Coffs to see my parents, but pretty much everybody else did. There were so many guys went up because the park was going to get closed, so many guys went up and skated and it just fuelled. It was like the first like flame of skateboarding, of our age group skateboarders just going. Actually this shit is real. There's heaps of us, let's get it going.

Speaker 1:You know, the Bones Brigade video had just hit and that was just insanely important in our generation of skating because for the first time ever apart from the occasional clip in a surfing movie or whatever the first time ever you saw guys in motion and you could understand the kinetics of what they were doing and you just went and it was just so incredible. I could still send shivers up my spine thinking about sitting at johnny bogart's parents place in the little rumpus room downstairs just going. Stop, pause, rewind, stop, pause, rewind. You know like watching those parts of tony hall, just like how the fuck, are we talking like future primitive?

Speaker 1:no, yeah, this this was the first this was the Bones Brigade video show yeah, yeah and and like I, like I know I mean it's such a cliche, but I I just so gelled with Lance Lance's part in that because he was it, it was so approachable like he just he was goofy but he was like it was so approachable Like he just he was goofy but he was like I was watching something yesterday of like one of the 80s Texas comps and he is so rad, like there's just so many parts, flip parts of his own thing over the last decade. He's such a good skater and he puts himself down so much. But he's like the velvet skater and he puts himself down so much. But he, he, he's like, um, he's like the velvet underground of 80s skateboarding. He like everybody who saw lance bought a skateboard. It's like the hardly anyone bought the velvet underground album but everyone who did started a band and that's what lance did for skateboarding in the 80s.

Speaker 1:He was like, uh, he just everyone went man, I can do that, I can tube right under a tree, I can do a board slide on a train, rail. You know, it's like I don't know if I want to jump off a roof, but I probably could, and so yeah, it just. And then you've got Hawk, like you think about that. That's the first Bones Brigade in 84, 85. The stuff he did in that bowl in his part, like you'd win a comp. You did that run now you'd still win a comp. It hasn't not a single 540 or spin. It was just insane and like that's way beyond us. But I can do what cab's doing, I can do what lance is doing, um, you know, and and it just got us going, really really got us going. We went okay, build a ramp. We've got to get ourselves off the ground and build a ramp.

Speaker 2:So it was Lance Mountain, it's his fault, it was Lance Mountain.

Speaker 1:It was bloody Lance Mountain's fault.

Speaker 2:He was the spark man. Yeah, he ignited that.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I think so, and so, yeah, we built the ramp in Ridge Street in 86.

Speaker 3:That's neat, and we could just finish now and say and the rest is history, that ramp is like, of that era of 1986 in Australian skateboarding culture.

Speaker 3:I mean, every magazine from that period has mention of the Merriweather ramp at least, or if there's ever like a kind of a scene check in the beginning any magazine and photos and little mentions of it were being mentioned right up until 1989 as well. In all of the. You know there's about five or six magazines during that period by that time coming and going and you see mentions of them like I think there's even like a blurb that says some stage in about the end of 88 that says a word on the street is that the Merriweather ramp is going to be back up and running again soon and you know that's it was two and a half years beforehand, wow.

Speaker 3:And yeah that was the Velodrome that was the Cockroach ramp. It was the same ramp.

Speaker 1:It was the same transitions, new timber, but the same transitions and the same.

Speaker 3:Do you want to tell?

Speaker 1:people about the 1988 Steel City Ramp Rage and what that was. Yeah, it was like the real, the nuts and bolts of it. Like, completely selfishly, the nuts and bolts of it was we just wanted to have a vert ramp again. And so to do that we organised this contest. We had this like a youth worker set up who sort of had some kind of connection to the council. She seemed legit. She got us forming an association. We used to have these meetings and the whole thing was quite tragic and horrible and in a smoke-filled room in her place in Hamilton South. But we organized ourselves together and decided let's have a contest. It's the bicentenary, we'll call it. You know, and that's how you get it through council, you make this big deal about it being connected to something, blah, blah, blah. But basically we just wanted to build a ramp again. So we still had the transition pieces I'm pretty sure they must have been at Coz's dad's concrete place and so my mate Andrew Gordon and I I just remember it you might remember when the contest was, but I just remember it being really freaking cold.

Speaker 1:We used to get up every morning about six. He was just like a boss. I ditched my whole life for like a month and I didn't go to uni. My girlfriend didn't know where I was, I just slept on his lounge and he'd get me up at six in the morning and we'd go to the Velodrome, which he lived in Broadmeadows, so it was like just down the road and we'd work every single minute of the light of day building this ramp pretty much just the two of us and Roy Lee from Pacific Dreams. He gave us trucks and trailers and money for wood and just like it was the most. He was just so incredibly generous and it was all on the back of this contest we actually had almost no interest in at all.

Speaker 1:In running the contest. We wanted our friends to come skate with us. So it ended up being the 1988 bicentennial ramp rage and it was a big deal like it. Actually. Heaps and heaps of skaters came, lots of younger skaters came. There are a couple of different divisions. Um, and it was a really, really cool experience um, cockroach ruined some money and we painted the ramp blue and spray painted cockroaches all over it, which was sort of yeah, it was so cool it was it looked, looked amazing.

Speaker 1:It was slippery. It was just like glass for the first few days, until the till the paint start stopped flaking I wish I had my skateboard here, because I've just got some cockroach wheels.

Speaker 2:How good are they.

Speaker 1:Yeah, and they've got the cockroaches back all over them like the old days Back in the day.

Speaker 2:Yeah, but yeah anyway, keep going, because I'm envisioning exactly what you're saying with that ramp.

Speaker 1:Yeah, and we ran the contest without really knowing what we were doing. I'm talking guys from everywhere, Like they just came from everywhere Gold Coast, Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney, and so everyone who was a skater. I've got no idea how we got the word out. Like I guess we called friends and sent letters, I don't know, really got no idea. Like I guess there was an ad in sent letters. I don't know, really got no idea. Like I guess there was an ad in the magazine, I don't know because, Skateboard Australia was up and running then.

Speaker 1:Anyway, heaps of people turned up. It was a contest. It was rad. The lady who was connected to the council, who was our kind of I don't know the person who galvanised us. We assume it was her who nicked all the money. Oh, no shit.

Speaker 2:Full extortion? No shit.

Speaker 1:It's just one minute we had hundreds and hundreds of dollars in a box and the next minute we don't have a box of hundreds and hundreds. It was just the weirdest thing. And then at the end of the day we had this gig in Merriweather High School Hall, which is just like. My son went to Merriweather High and when I tell him he's seen pictures and he's just like that's just insane. Like I've been up there on the stage shaking principal's hands and you were up there being a punk on the same stage when your guitarist was banging his guitar on the ground of the place where the principal was standing. It's so funny.

Speaker 3:There's skateboarders from all over the country as well. I mean that competition, to put it into perspective, probably made up, without exaggeration, probably 15% of every magazine for the rest of the year. As far as either, whether it's I mean there's obviously just the coverage of the comps wasn't that big. But then in every little photo gallery, because we're talking there's during the period, there's Skateboard Australia, skate and Life Slam, perfect Transition, still a thing, 540 is still. So there's a lot of Australian magazines that you know on magazines like on the newsagent shelves at the time, and all of them had coverage. Oh, speedwheels as well, sorry to go back, the one Chad Ford edited, great magazine, in my opinion kind of under, not given the respect that it was, because maybe people thought it was corny, but it had some great photos of the rampage as well.

Speaker 2:Do you think it was just the timing? The timing was just so spot on as what everyone needed at the time.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I reckon it was just the timing. The timing was just so spot on as whatever needed at the time yeah, I reckon it was pre the council's getting on board with facilities. So, like I said, it literally was just so we had somewhere to skate, yeah, and we skated that. Right, we skated it, I don't know, maybe a month, I don't know how long it was up for, and, um, of course, you know, some guys got in that weren't skaters and graffitied around the velodrome and the velodrome people who were happy to have the ramp there because it was just in the middle of the velodrome where there's just blank space.

Speaker 1:Yeah, they didn't want people coming in and messing with their shit. So they just said oh sorry, boys, you're going to have to pull that down. So you know it was. But by then, like we were going to Mona Vale, kell Park, bell, rose, they were really good Sort of you know it's a hassle. I used to go to Andrew and come around on his motorbike again, I've got memories of it just being cold all the time. But he'd come around on his motorbike and we'd just chuck bags and stuff on the back of this I don't know 550 Honda and drive to Sydney in the freezing cold.

Speaker 2:No shit, we get there like seriously, like double, getting doubled.

Speaker 1:Yeah, doubled on a motorbike with two skateboards and two like pad bags From Newcastle to Sydney like two and a half two hours.