Fresh Growth

Fresh Growth

Royal Dairy: Ruminants, Carbon Sequestration, and Soil Health

Austin Allred, talking about his family's Royal Dairy in Washington, proudly states that rather than contributing to climate change, Royal Dairy shows that farms like his can be an impactful part of the solution — in part by preventing the formation of greenhouse gases and boosting the capacity of his soil to draw down and sequester atmospheric carbon.

In this episode, Austin shares his passion and knowledge about the relationship ruminants have with the soil, which effortlessly leads to regenerative and sustainable farming.

You'll hear about the importance of ruminants converting rotational crops to proteins valuable for human consumption. Austin also discusses carbon sequestration and how regenerative farming is the process that brings carbon into the soils. We need to bank carbon in our soils, and the role ruminants have in this process is significant.

And you'll hear how Royal Dairy captures 70% of their animals' urine and manure and runs the liquid manure through 8 acres of worms combined with rock and wood chips to capture usable water and high value worm castings.

The family's long term approach has led to fewer inputs and more outputs with the worm and compost farm.

____________

Thanks for listening to Fresh Growth! To learn more about Western SARE and sustainable agriculture, visit our website or find us:

Contact us at wsare@montana.edu

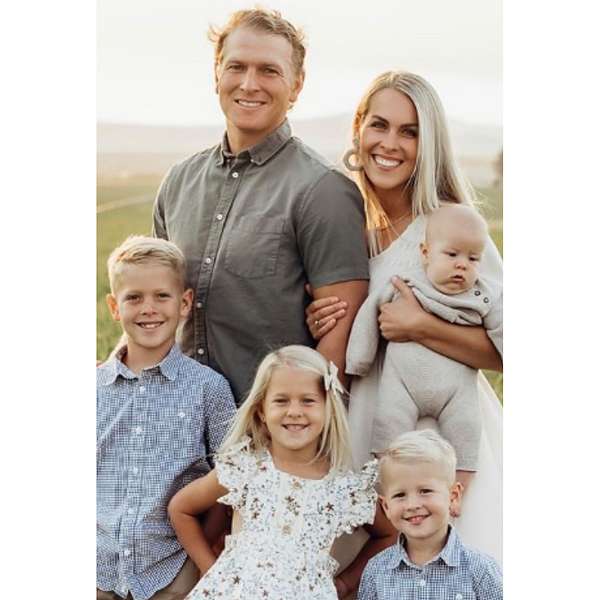

Welcome to season three of fresh growth, a podcast by the westerner program that sustainable agriculture research and education. I'm your host, Steve Elliot, alongside co-host Stacy Clary, just for background westerner promotes sustain farming and ranching across the American west through research education and communication efforts. Like this podcast, it is funded by the us department of agriculture's national Institute of food and agriculture, fresh growth introduces producers and ag professionals from around the west who are embracing new ways of farming and ranching. They'll tell us about their experiences adopting more sustainable agricultural practices and the challenges and benefits they've seen. Today's guest is Austin Allred, owner of Royal dairy in Royal city, Washington. He lives on the third generation farm with his wife, Camille and their three kids, their website, proudly states rather than contributing to climate change. Royal dairy shows that farms can be an important part of the solar ocean in part by preventing the formation of certain greenhouse gases and boosting the capacity of soil to draw down in sequester atmosphere at carbon Austin. Welcome, and thanks for sitting down with us.

Speaker 2:Welcome Austin. As a start, it'd be helpful to hear a description of your area in Washington.

Speaker 3:So we are in the middle of Washington state. If you know, Spokane, you know, Seattle go right in between them. You'll find Royal city, it's called the Columbia base and I am biased, but arguably we're sitting in one of the greatest irrigation projects in history called the Columbia base irrigation project over 200,000 acres here through a series of hydro electric dams, which allow us to utilize the water through a series of canals through the whole basin and, uh, make for some of some really, really, really good farming farm ground, and a great farming area. Our dairy sits in the middle of that. We, uh, we milk on this side about 6,500 towels, and then we have a beef ranch that, uh, we team up with that, that we own also that does, uh, another 5,000 beef animals. My father is a potato farmer. Um, so we certainly work together. The relationship with the soils and the ruminants is something that we very much value and believe leave helps our soils a lot. So, and then there's also an orchard to my father. Does my brothers do apples and cherries. And that farm also is a sister company to the dairy and the ranch that it's all a, a symbiotic relationship to where the soils and the ruminants and the byproducts and the cover crops are all working together to create a very system

Speaker 1:About how, how all that works in more specifics. I mean, walk us

Speaker 3:Okay. How much time do we got<laugh> I get going? I can get going, Steve. So, okay. So the cycle, uh, Steve, I could go all day every day on this. This is kind of what I really am passionate about. It's the relationship that ruminants have with our soils. And, and really with that relationship, we start talking about regenerative farming and sustainable farming. I'll start, I'll start by just, and Steve, please kind of shut me down or, or chase me hot, chase me in the certain directions that you'd like, don't let me, don't let me steal the, the

Speaker 1:Direction, if it's going way, way, way sideways. We'll we'll bring you, but otherwise listen to you talk about, this is what we're doing here. I mean, that's, that's why we wanna be here.

Speaker 3:Okay. So there's really, when you, when you start talking about soils and ruminants and the relationship that they have together, that effortless effortlessly takes you to regenerative farming and regenerative farming has a few different pillars that make up regenerative farming. And I like regenerative farming, cuz those pillars are different in different regions. And that's why it's really, uh, important that regenerative farming is a focus of ours in the future. The adaptive nature of regenerative farming allows us to be sustainable in our, in our certain ecosystems. Um, here cover crops, very important that that goes in with, uh, rotation crops. It's very important to be adding different biodiversity to your soils year, to year, to year, to year, uh, introducing the ruminants, the, the, the manures into your system into your soils is very important to regenerative farming. Those all kind of tie together, cover crops, rotation crops, and the manures is all just the biodiversity of your soils. The cover crops is in part keeping your soils from blowing away also, but, uh, those are working together to give you diverse soils that are healthy for the long term. And then, uh, the other thing that you gotta consider is tillage and then just water usage. Um, but if you can, if you can work those together and figure out your systems within those, um, you're getting more and more regenerative. So specifically what we've done here on Royal family farming, uh, with our ruminants and with the potato farm and with the orchards is you take the rotation crops, which by, by default, you think about, you think about what humans eat versus what ruminants or towels eat. And it's different things. The ruminant is able to convert grasses, even corn, which a human which our digester system can't utilize very well. The grasses in the corn, the ruminant is able to convert that to proteins, which are very valuable to us. Along with this conversation, you need to consider that the, the crops that are produced for humans are generally the crops that are going to deplete your soils a little bit more because your soils and your plant have to work a little bit harder to get that food to a state that we can digest it. So if you back that down, you need the ruminant crops. You need these cover crops to be part of that rotation. The alfalfas, the grasses, um, even the corn, those crops are really critical to healthy soils and that rotation. Um, so Steve kinda talk me through that. I mean, I know that's a lot and I just kind of bombarded that. So anyway, I'm sorry. Yeah. Let

Speaker 1:Let's talk. Let's talk about it in, in practice with the three different aspects of the farm. I mean, if, if you've got the Ru inside on the dairy, what's coming in, what's going out and how is that all helping the whole system?

Speaker 3:Yes. Um, I have a whole bunch of, uh, I have a whole ecosystem on paper that shows all of the inputs and all the outputs. So when you say going out, most of the time what's going out in our farm is crops for human consumption. So for us that's potatoes, apples, cherries for us, we do some sweet corn and we do some like snap peas or green peas. And on occasion we'll do some wheat. So that's the outputs, if you will, in this conversation, those that's what our farm and goes to Walmart or somewhere else. But we also are pulling a lot of that back. Anything, any of those crops, we have relationships with those processors. Some of them, we own those processing, any of the byproducts that don't quite make grade or get run over in the process or potato skins, French fries that don't make the right cut apples that are the wrong size peas carrots. We're feeding tons of these byproducts. We're bringing those back to the ruminants to convert'em to proteins. So then, um, those are the outputs that's, what's going out. Some of those byproducts are coming back and then the ruminant is then, and utilizing those crops, the crops that are staying here, all those cover crops, it's all those grasses. It's all those, I'll say'em soil benefiting crops. I mean, not that not that potatoes are bad for the soil, but potatoes back to back to back to back are certainly bad for the soil. So the crops like the grasses, um, that really are good for soil. Those are coming to the ruminants, whether we do it through the pasture program or whether we harvest them silage and feed. Um, and then the ruminants are utilizing those crops to make milk and meat, the best proteins in the world. I'm biased, but the best proteins in the world. Um, furthermore, the ruminants are filling the rest of that plant, that it just consumed with microbials, putting it out the back end, and we're then important part of the formula utilizing it correctly with best practices, utilizing that manure, right? So that we can then without releasing all that carbon at that plant and that room, and it have utilized up to this point and, and sequestered, if you will, we're taking that manure, getting it to a point where we can then put it back on the ground in a, in a healthy way.

Speaker 2:And talk about more about the se sequestration and your, um, your comment about how you are, um, actually a solution to climate change. How does that all tie in?

Speaker 3:So, um, soil carbon sequestration is one of the major answers to taking carbon out of the air where there's an excess, we have too much carbon in our air and putting it into the soils where we have a need. We need more carbon in our soils. Regenerative farming is the process that does that. It is the process that, that makes that inverse happen, takes it outta the air where there's too much and puts it in the soil where there's not enough. Um, carbon in the soils is good, like period, right? I mean, there, there's not, I'm sure there's a balance, but we wouldn't even know it cause we're so far away from it. I'm sure you can get too much carbon, but we don't even know what that looks like. It's not even on our radar because there's just frankly, not enough. So, so at the end of the day, we need to bank this carbon in our soils and, and the role that the ruminant has on that is significant. As I've mentioned, those crops that we're growing are the crops that are most beneficial to soil, carbon sequestration. Um, furthermore adding the, the, if you think of the carbon chain, you pull it outta the air that plant utilizes photosynthesis and, and traps that carbon, it sequesters that carbon. But then if you go out and you a put it through a cow, lose a bunch empirically, which there is some of that, that's a, cow's gonna burb. But then if you allow that carbon to be all dismissed back into the year through poor manure management practices, then a really you are going backwards. Furthermore, if you, you take the carbon that your plant has with correct practices, your plant has sequestered and even banks in the soil. And then you go and till your ground a whole bunch and plow it and open up that ground the same you're, you're gonna lose a lot of that carbon, which a lot of effort has gone into to keeping it there. So keeping that carbon within that chain, through the ruminant, and then back to the soils is really the trick to sequestering carbon instead of just utilizing photosynthesis and releasing it all and pulling it. You, you see what I mean? I mean, at some point you put it in soils and you, you trap it there, you bank it. And over time you are getting more and more carbon in your soil to where you're not just sequestering your banking and that's what we are tracking. And that's what we're doing on our, um, on a daily basis.

Speaker 2:And you you've mentioned, uh, best practices and you mentioned not using poor manure practices. What are some of the practices, the best practices you are incorporating as far as, uh, manure management?

Speaker 3:Yeah, we use a lot of practices. So to preface this there's three main areas where an, uh, animal a, a CAO, if you will, a, an animal operation is gonna, is gonna have a footprint. You're gonna have a footprint, empirically cows, all mammals, we're going to burp. We're going to release gas cows, don't fart. Their stomach is way too advanced for them to be farting. Um, there is an entire commission that comes with those animals. Two just overall management, when you're your practices of harvesting and of getting the feed to the animals, there is a footprint there. Um, but, but there's a, there's a manure management footprint that actually takes up probably the biggest, um, of that footprint. Am I making sense? Stacy am, I guess, okay. Saw me if I'm scrambling. But the biggest part of that footprint is, is probably tied up and most operations is tied up in that manure management side. So here we've employed a few different practices to try to make sure that we don't allow that carbon, whether it's in methane or ammonia, be released until we want it to be released into our soils. So I'll just explain briefly, we collect as much manure from our animals as possible, and that's that the vast majority of it, um, 70% of all the, or a urine that our animals give we capture, we then take that to a central location where we immediately use slope screens to pull out the so manure and leave us with a liquid manure. And we have a couple different phases, a couple different slope screen sizes, a primary slope screen, then that then that liquid manure will go through a, a sand lane into a secondary slope screen. So at the end of the slope screen, sand lane slope screen process, we're left with quite a few solids, which immediately go to compost and we're left with a dirty, we call it green water at that point. Now that green water is generally where the biggest, the biggest portion of your manure management footprint is going to come from is from that green water. It's from those lagoons that are going to be bubbling and releasing methane. As they're sitting there digesting, we take that green water within a couple of days of formation and we put it, we give it, we feed it to our worms. We have eight acres of worm beds. It's the biggest bio filter in the United States that we sprinkle out that green water on top of, and those worm beds are layered with warm castings, wood chips, and rock. The green water comes out. Those sprinklers settles through the worm castings, wood chips, and rocks, which sidebar is really a copy of God's creation. Um, if you think about rain or water, it's contaminated, it's contaminated as it rains, it's contaminated the, as it touches our earth, whether it falls on manure or not, it's contaminated. And then it settles through the layers of rock and earth. And then we pump it out of the bottom and we drink it. We've condensed that into a five foot version. We're not necessarily going for potable. We don't get potable out of the bottom of that, but we certainly get irrigation type water. So as that dirty green water settles through, it's gonna pull out the vast majority of the nitrogen, the phosphorus and the potassium about 85% of NP and K is gonna come out of that water. And it's captured in those worm castings in the, in the, the media there we're then going to utilize that the clean water that comes out the bottom 75% of that is gonna go back into our system. And we're gonna use that to flush our barns and to clean, to clean our animals, not, not to clean our animals, to clean the barns and the homes of our animals. Um, the other 25% will go to our lagoon, which is now an irrigation pond. And it's gonna go through the, the irrigation system when we need that water to water our sprinklers. So the only potable water we use on all of our farm is the water that our animals need to drink. And the water that the FDA requires us to use in our parlor and in our cleaning systems that comes in contact with milk or, or meat, um, everything else is irrigation water, or this, this, uh, we call, we call it tea water at this point, which is an irrigation water. So that's the water that's, that's how we utilize the water. And it's, it's a really good system, but then potentially even more exciting is what those worms do with the N P N K, that they pulled outta that water. They're going to crawl around that biofilter all day every day and be digesting that NP and K, along with the wood chips that we are already cap, we're keeping the carbon in those wood chips, putting that in the media, and they're gonna be digesting all that carbon and all that NP and K, and you'll hear me say a lot. Uh, a cows digestive system is off the charts. It's the coolest thing in the world. Second place very closely is a worm digestive system. When worms digest something for whatever reason, I'm not a, I'm not a good biologist, or I don't even know if that's a biologist quite, but anyway, when it goes through a worm digestive system, it poops plant ready gold. It really does. They're called worm castings. So those worms are crawling through, they're taking the NP and K taking the carbon that's in the wood chips that we've, that we've captured in, in many cases, we're taking that off of our orchards, which are not getting burned, cuz that's the common practice right now. You get, you get burning all over the place to try to control that we're taking those wood chips and building value in them, putting'em in this media to be a water filter. The worms are gonna digest that, upcycle that with the NP and K and turn into worm castings, we're gonna harvest those worm castings on a, on an annual basis and we're gonna sell those for or use'em on our farm for a soil amendment, long answer.

Speaker 2:It was good answer. I'm very passionate and a lot of knowledge. And I guess I could guess there's a lot that you're, uh, really passionate about and what you and your family are doing. How did this start? How did you begin looking at soil health, regenerative agriculture, the whole cycle, how long that's been going on and are you taking it step by step or did a lot of stuff change very quickly?

Speaker 3:And yes,<laugh>, uh, 10 years ago, a little more, about 10 years ago, my dad being a potato farmer and an, and an apple farmer, um, the, the neighboring dairy farm came up for operation. And, and at that point I had just graduated from school and it was our ambition to get into the dairy, into the ruminants, if you will, to support their farm, I'll be honest. I didn't want a potato farm or apple farm. So I was doing it. My motives weren't maybe as pure, but I wanted it. I, I loved the cows and I loved working with the cows. And so, but my dad willingness to support me in that venture was based on the idea that we could utilize those ruminants to support our current farming operations. So that really you frame that up a decade ago like that. And it's, it's been my goal that whole time to work everything off each other and to keep this regenerative agriculture system going to keep it long term, you know, that's really what it comes down to. It's a long term versus a short term approach and, uh, and regenerative agriculture. And what we have going on here is a long term approach.

Speaker 1:What have you seen change in the potato farm in the past 10 years,

Speaker 3:Less inputs? So our potato farm is not organic. Um, it it's close to, but we, we don't, we're our processors, French fries and stuff, but anyway, it's not an organic farm, but it doesn't matter because we are buying less inputs. We're, we're spending less money on bringing outside sources in to support our soils for a short term window, right. Cuz N P and K is a very check your soil sample, put some, put some process NP and K and solve the problem for that season. Right? Whereas we are in a long term approach where we're adding all these inputs in a RO in a rotation form and a, and, uh, and it's, it's progressively getting better and better as far as a inputs, um, coming from elsewhere for our soils and Steve to continue on that. I know I always continue on your questions that you probably want a two minute answer and I give you 15, but, uh, to continue on that, we have more outputs. If you will, we have more, more value coming out the others side, not just are we a potato farm now or, or an apple or a cherry farm? Um, we're not just a, we're not just a milk or meat farm, but we are a worm castings farm. We're a worm farm. We're a compost farm, we're a manure farm. And all those pieces are working to together to create more value, uh, in general, because you have more valuable. I don't even wanna say commodities because I don't like commodities per se, cuz I feel like farmers are just getting rigged over the coals via the commodity game. Um, we sell wholesale and buy. Um, but we have all these products, these commodities<laugh> that support us and support each other.

Speaker 2:So the changes have benefited the land and, and your operations, but your bottom line as well. That sounds like,

Speaker 3:Yeah. I mean short answer is yes, law long answer is all these changes, cost money. We have more revenue long answer is we've we've, we've spent a lot of money in the last decade to be constantly tweaking and improving our practices. Mm-hmm<affirmative> but we're getting there and we feel very comfortable with the direction we're going from a very business standpoint. Mm-hmm<affirmative> mm-hmm<affirmative>

Speaker 1:You guys, your Emily has had the advantage of, you know, the three different operations and being able to work, you know, together and support. Can you see this kind of approach working for another, with another potato farmer who doesn't have, you know, the dairy, but can link up with someone else's dairy. I mean, can you see farmers moving this way, even if they're not related to each other, I guess is the, is the, the short version of that question?

Speaker 3:Yeah. In the short version answer is most certainly there obviously has to be a certain geograph balance, um, for, for it to work really sustainably. Um, the ruminants need to be close to the farm, close to the processing even for the byproducts. But short answer is yes, it, it is a very symbiotic relationship and Steve we're doing it. I mean, I, obviously the focus is our family, but I sell a lot of manure and I, I take a lot of byproduct from outside sources and, and so we're, we really are doing it. It's it's about the balance of ruminants to soil, um, to crops. I mean, it really is about that balance. You don't have to be related. We just fortunately are. Yeah.

Speaker 1:Right.

Speaker 2:And you have a lot of family members together that worked for really well. How do you, how do you come to decisions together and stay on the same path and work things out?

Speaker 3:Uh, we just fight a lot. We just wrestle. I'm just kidding. No, we are fortunate because there is these different branches, apples, potatoes, ruminants, we all have our own roles. Um, which is very fortunate. I think that keeps us from stepping on each other's toes too much. Um, but then we most certainly come together and, and try to improve the systems. I mean, I'll just say for the most part, usually the answer is pretty symbiotic. You know, it's not, Hey, I need this for my cows, but usually that's supporting the soils and usually that's supporting another crop or, or something. So it works pretty good to date Stacy, but I am the strongest. So usually I just win.

Speaker 2:<laugh> got it.

Speaker 1:Stay it on the, on the family theme. You've you've got kids. Would you like to see them go into farming or what's, what's your vision knowing that kids do ever, they want to do eventually.

Speaker 3:Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it, it is interesting, Steve, cuz really what I've, what I've learned is I've gone out in the world and they come back is farming is unique. Agriculture is unique that we're long term. I mean it is very generational and it's one of the few, uh, histor that is like that, you know, the whole EBITDA and valuation and sale for 10 X. We don't even know what those terms mean or are, and they don't even cross our board board meetings. Like we have board meetings, our family center discussion. And so with that, it really plays into regenerative agriculture and the processes that we're working towards to make these operations sustainable. Not just five years, not just 10 years, not just 20 years, but literally lifetimes and next lifetimes. So I don't know if that answers your question, but yeah, I would love, I would love to have a very awesome operation, sustainable regenerative operation that the kids can jump onto if they so desire. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 1:Not a bad goal.

Speaker 2:And it's, as you, uh, been working with the family, have you made some changes that Jess did not work out

Speaker 3:<laugh> oh yeah, I'm sure I have to think about em, might try to erase those ones from memory, but<laugh>, if I need examples, you might need to gimme a few minutes to, to come up with them. But always change is hard. There's no way around it, but progress, change improvements. It just flat takes work, learning the right way to progress. Most of the time flat takes screwing up a lot. So I can't sit here and pretend like we've, uh, we've cheated that system in any way, shape or form. So lots of mistakes, lots of work, but we're focused on the right goals. I think keeping our, our earth in check, I I've feel strongly that ruminants have a great role in balancing out that system, um, to keep our are, to keep a balanced diet in our, to keep a, a balanced diet, a but a balanced environment too.

Speaker 2:Awesome.

Speaker 1:So I'll, I'll ask you the last question and, and you sort of touched on it a little bit already, but so what advice would you give, you know, a young farmer or rancher, um, who wanted to farm better, more sustainably or even not a young one, an old one. Um, but wanted to rethink the way they farm for the long term

Speaker 3:Buy a cow. I will. I mean, as I, as I mentioned with my family, I'm, I'm the, I'm the cow guy, I'm the ruminant guy. So, um, I'm biased. But I do think that when you add the ruminant to the system, not only do you get the incredible proteins that that ruminant is producing for us, but you get their byproducts and you get to grow crops that are good for your soils for those cows. Um, so you get that ruminant sitting right there in the middle of your system and it just, it opens up so many doors for really all of it. And then you start throwing in worms and you throw in, uh, different some of these different, you know, winter crop that are so fun and you you're on your way to a really awesome regenerative system that improve, you know, improves your revenue, increases revenue with different outputs. Um, but then also decreases the need for external resources to keep things going

Speaker 2:Well, you shared a lot. It was a really fun conversation. Um, I definitely heard the passion and I learned a lot. So, uh, thanks a lot for sitting down and talking with us. Appreciate it.

Speaker 3:Feel free to reach out. I'm happy to continue the conversation. Add more. I'll speak last.

Speaker 1:We wanted you to speak it worked great. Yes. Thanks Austin.

Speaker 2:Really appreciate it. Yeah. Thank you.

Speaker 3:Sounds good. Thanks. We'll talk soon. All right. Take care.

Speaker 4:Thank you for listening to fresh growth. We hope you enjoyed this episode for more information on westerns rounds and our learning resources visit Western sarah.org.