Everyone Dies (Every1Dies)

A thoughtful exploration of everything about life-limiting illness, dying, and death. Everyone Dies is a nonprofit organization with the goal to educate the public about the processes associated with dying and death, empower regarding options and evidence-based information to help them guide their care, normalize dying, and reinforce that even though everyone dies, first we live, and that every day we are alive is a gift.

Everyone Dies (Every1Dies)

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators (ICD) and Things You Need to Know at End of Life

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) are a technology that many people have, especially if they survived cardiac arrest or have a heart condition that causes dangerous heart rhythms.

ICDs are a great technology, but at some point a decision may need to be made about continued use or turning it off. This show will help you understand the issues involved and five considerations for making this decision.

In this Episode:

- 00:00 – Our Sponsor: Tree of Life Memorials and Digital & Stone

- 00:20 – Intro

- 02:03 – Richard Lewis in “Curb Your Enthusiasm”

- 05:31 – “Much Ado About Dying” Documentary Review

- 08:48 – Recipe of the Week: Charleston Chewies

- 11:35 – Overlooked No More: Beatrix Potter

- 16:50 – ICDs and End of Life

- 35:53 – “This Confusion” – a poem

- 37:49 – Outro

Get show notes and resources at our website: every1dies.org.

Facebook | Instagram | YouTube | mail@every1dies.org

Implantable-Cardiovascular-Defibrillators-ICDs-and-things-you-need-to-know-at-end-of-life

This podcast is sponsored by the Tree of Life Memorials and Digital in Stone. This is a new platform to create digital memorials, environmental legacies, and fine art monuments. This way we could share the stories, preserve the memories, conserve the land, and connect the souls because love never dies.

This podcast does not provide medical nor legal advice. Please listen to the complete disclosure at the end of the recording. Hello and welcome to Everyone Died as the podcast where we talk about serious illness, dying, death, and bereavement.

I'm Marianne Matzo, a nurse practitioner, and I use my experience working as a nurse for 45 years to help answer your questions about what happens at the end of life. And I'm Charlie Navorrette, an actor in New York City and here to offer an every person viewpoint to our podcast. We are both here because we believe that the more you know, the better prepared you are to make difficult decisions.

So welcome to this week's show. Please relax, get yourself something bolstering to drink, and have some pie. And thank you for spending the next hour with Charlie and me as we talk about implantable cardiovascular defibrillators and things that you need to know at the end of life.

Like the BBC, we see our show as offering entertainment, enlightenment, and education and divide it into three halves to address each of these goals. Our main topic is in the second half, so feel free to fast forward to that gab fest free section. In the first half, Charlie has a new installment to our series about forgotten obituaries and our recipe of the week.

In the second half, I'm going to be talking about implantable cardiovascular defibrillators, or ICDs for short, and how they help with symptom management for people with heart disease. But there needs to be a plan for dealing with them at the end of life. So we'll talk more about that.

And in the third half, Charlie has a poem about growing old. So how are you doing Charles? Well, overall, fine. I can't complain.

Of course, I still do. Well, you know, a couple of quick things you had mentioned before in a previous podcast. Watching Curb Your Enthusiasm, that Richard Lewis, you know, the comedian who recently died, you could just see how awful he looked.

So I borrowed a cup of HBO from a friend. I saw the first couple of episodes where he's in it. I don't know, Marianne.

I mean, I mean, his timing was still impeccable. But I remember you're saying he looked like, you know, death warmed over. I mean, he looked pale.

And I noticed on one hand, he wore a white glove. But as far as, you know, Parkinson's, I saw none of that. So I don't know.

Was he just able to control himself in some way? Or was it like in later episodes, where he just was literally shaking and that stuff? No, I think what I said was, I didn't see that. Yeah. No, I think what I said was, though, I didn't see any of the symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

And that he did his role well. It's just the fitness, his color. Oh, that.

Oh, yeah. You know, hang in a room with nurses. We go through and can diagnose just about everybody looking.

We're terrible at, you know, we just can't stop ourselves. So I saw that. And it was the episode that was his last episode, which was the one that would have aired.

Okay, like last week, because right at the beginning of it, they put in, you know, they'll put in when somebody dies. It was right at the beginning of that they put in that he had died. And it was that episode, from the previous to that last one.

It was like, Whoa, do you have to? I don't know, whatever week that that one is, or look at the week that he died. And then go to that episode. And yeah, yeah, I think it was it.

Okay. Okay. I will then.

Okay. Yeah. I'm sorry.

Yeah, I just have not seen the entire season. Okay. Yeah.

So that would have been like, toward the end of February, maybe the first week of March. Yes. All right.

Yes. Got it. Yes.

Or, in fact, when I saw that, at least from the shaking point of view, pretty well managed, because I didn't see that at all. Yeah. It's just that his coloring and the thinness of him was really different than at the beginning of the series.

Yeah, yeah, he already looked, you know, pale and pasty in those first couple of episodes that I've seen. Okay, got it. Second, just to let you know, I saw an interesting documentary last night, called Much Ado About Dying.

It took place in England. This man, he was many things, among them a teacher, he was in India, he had done some acting, and he started to get phone calls from his uncle. I mean, this gentleman's British, was living in India, started to get calls from his uncle, and an actor, and a teacher.

This time in his 80s, and just kept calling him. And finally, he would, you know, you know, asking, you know, you know, can you come and see me? Can you come and see me? So the filmmaker, David, who was, I need to write this down. Anyway, so he went back to England to, you know, to visit his uncle, and then wanted to spend the next four years looking after him as his uncle continued to deteriorate.

Yeah, it was, it was, it was just interesting. I mean, he was there for him. It was not a peaceful transition.

His uncle could really could be a real pain in the ass. Not, not like, you know, angry or anything like that. But just following simple, you know, everyday details, like, take your medicine.

You know, eating proper things. He was a hoarder. Yeah, it was just interesting to see what, you know, also the transition not only for for his uncle, but also in himself.

And that sometimes he just, and it was nice. And I say this specifically, because as a caregiver, there were just times he just really hated it, did not want to be there. He had other things to do with his life.

His sisters lived far away, were really not able or willing, to be honest, to help out much. But in the end, he just knew what he had to do. And it was just nice to see the whole thing where that somebody, your caregiver gets angry and frustrated.

And you know, what the hell am I doing here? And then just gets on with, you know, helping his uncle, you know, just to navigate everything. So yeah, much ado about dying. It just opened here in New York.

I mean, literally last week. So yeah, so folks, is it a film? Yeah, it's a documentary film. Yeah.

Yeah. Yeah. So it was interesting to see.

Okay. Yeah. All right.

So let's jump right into this. Well, thank you for that report. Absolutely.

Absolutely. Absolutely. So in our first half, our recipe this week is a chewy confection made with pecans, butter and sugar called Charleston Chewies, which are a South Carolina original recipe that comes from the Gula Geechee cuisine.

Marianne, I have a quick question. What the hell is Gula Geechee? You know, you need to do your research prior to recording. Yes, of course.

Okay. I'm familiar with a Charleston chewy. I remember seeing those I went up.

That's your mama. If you could say that again. Yeah, I never I don't remember liking these especially, but this is interesting that you can make them at home, which I imagine would be far better than you pick up at the store.

Well, these are, these are like, like, like a brownie type thing, as opposed to the Charleston chew, which was it? Oh, yes. Okay. That's what I've had the candy.

I've never had the bad boys as I'm sorry. It's like a brownie. Yes.

Yes. Good. All right.

Sort of like ish. Well, yeah. Because you mentioned that that they're in bakeries.

So I should figure that out. Anyways, with these thingies, Charleston Chewies, which are a southern original recipe that comes from the Gula Geechee cuisine. Geechee, Geechee.

Who sang that? The Pointer Sisters, right? Wasn't there in some lyric? Geechee? Something. It was, wasn't this? I don't know. Yeah, I mean, all right, fine.

We'll leave it. But there it is a rich area of the country and culturally very interesting. Interesting and well, nevermind.

Let's not go there. The common dessert or snack staple. Respectful.

Let's not go there. The common dessert or snack staple can be found at many bakeries in the low country of South Carolina. Many recipes have been passed down over generations from their enslaved ancestors and are coveted by each family.

This version of the recipe requires just seven main ingredients all readily available at any grocery and needs only 20 minutes of active prep time to whip up. And if I make a rope for a moment, and intoxicatingly delicious without all the work, they will lead the sweet elegance to your next funeral lunch. Bon Appetit! Moving on, another smooth transition.

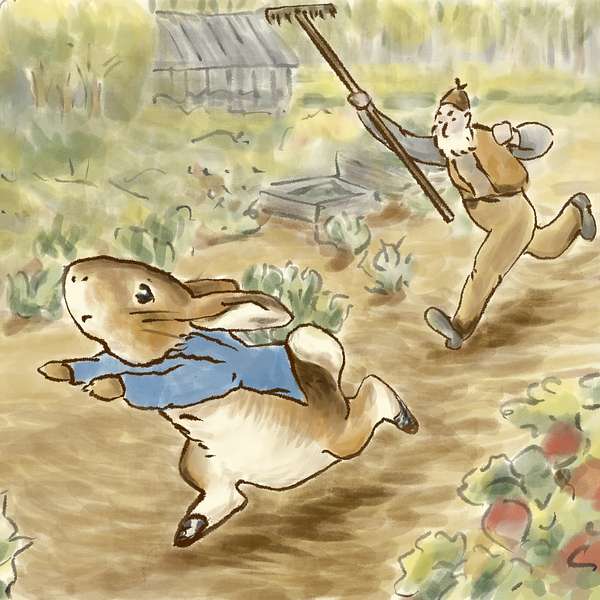

Overlooked is a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths beginning in 1851 went unreported in the New York Times. Today, I will be talking about Beatrix Potter, author of The Tale of Peter Rabbit, who got a mention when she died, but not an obituary. Beatrix Potter created one of the world's best-known characters for children, Peter Rabbit, and fought to have the book published.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit is about a cheeky rabbit who steals vegetables from the garden of Mr. McGregor and loses his coat and shoes in a narrow escape. It has sold more than 45 million copies and spawned a merchandising empire. In 1900, Potter, in her mid-30s, submitted her book, complete with her own intricate illustrations, to at least six publishers.

The rejections flowed in. She decided to print it herself. She took her savings to a private printer in London and ordered 250 copies of the book, which she distributed herself.

The demand was so great that she needed to print 200 more. As books flew off the shelves, Potter sensed a merchandising opportunity, so she designed a Peter Rabbit doll, and soon there were china figurines, wallpaper, and more dolls, products she jokingly called sideshows, though she involved herself in their design, copyright, and quality control. Potter went on to write 22 more books.

Her characters, dressed in waistcoats and bonnets, were rendered with meticulous attention to anatomical detail, an outgrowth of Potter's long interest in natural science. Her father was a barrister. Her mother, a daughter of a successful merchant.

She and her younger brother, Bertram, collected insects and frogs, caught and tamed mice, and trapped rabbits to observe them. She drew them, and just about everything else, endlessly. Bertram was sent to school, but Beatrix was not.

She was taught by governesses, took art lessons, and made regular trips to the Natural Museum in London to find specimens to draw. In the mid-1890s, he sold drawings of frogs and other work to a fine arts publisher. Potter wrote what she called picture letters to the children of a former governess, Annie Moore, who suggested that Potter turn the letters into books and sell them.

About a year after Peter Rabbit was published, there were almost 60,000 copies in print. The world that Potter conjured in her books, whimsical but dark and full of bloodless observations about the food chain, appealed as much to adults as to children. Maurice Sendak, author of Where the Wild Things Are, who acquired rare copies of Potter's books, acknowledged being influenced by her work.

Miss Potter never sought to be a celebrity. She used the money from her book sales to buy and preserve the farmland that had inspired her tales, and as she grew older and her literary output slowed, she increasingly devoted herself to life in the country, eventually becoming a prize-winning sheep breeder and conservationist, and continued buying land with William Heelis, a lawyer she married when she was 47. Potter died of heart ailments and complications of bronchitis on December 2, 1943, during World War II.

Though her death was not initially reported by the New York Times, the newspaper referred to it in subsequent weeks and months, noting that she left behind an estate worth $845,544, roughly $15 million today, and that Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, had bought all 15 copies of The Tale of Peter Rabbit from a London bookstore to keep at Buckingham Palace. Upon her death in 1943, aged 77, Potter left 4,000 acres of farmland to England's National Trust, a conservation charity. Pretty cool.

Wow, that was generous, huh? Absolutely, absolutely. And if anybody has any land they want to leave us? Yes, and with that in mind, please go to our webpage for this week's recipe for Charleston Chews and additional resources for this program. Your tax-deductible donations are always welcome so that we can continue to offer you quality programming.

Thank you in advance for making your donation at www.everyonedies.org. That's every, the number one dies.org. Marianne? Thanks, Charlie.

Second Half

Today I want to chat with you about implantable cardiovascular defibrillators, which from now going forward I'm going to call ICDs because that's a mouthful. This might be a piece of technology that you know about, and for others this will be something new and completely different, but I think it's something everyone should be aware of because you never know when you might be standing at the deli counter and the person next to you has their ICD go off and you have no idea what's going on.

But after this, you will. To understand how an ICD works, it helps to know how the heart beats normally and how it your lungs, your brain, and the rest of your body. It has four chambers, two upper ones called the right and left atria, and two lower ones called the right and what pumps blood around your body.

Your heart's pumping action is controlled by tiny electronic impulses produced by a part of the right atrium called the sinus node. Your sinus node is your heart's natural pacemaker. It sends out regular impulses that travel through an electrical pathway in your heart.

These impulses help to coordinate the chambers of your heart as they contract and pump blood through your heart and out to your body. This is what causes your pulse. A healthy adult heart has a regular beat that's usually between 60 and 100 beats per minute while you're resting.

When you exercise, it may go up depending on your age and how fit you are. You put your finger, you know, follow your thumb up to your wrist and there's a little kind of edge in there. Put your fingers in there and you can feel your heartbeat.

You hear boom, boom, boom. The first boom is the contraction of the upper part of the heart and the second boom is the contraction or the squeeze of the lower part of your heart. These impulses, you may have heard of a pacemaker which sets the heart rate for people with slow heart rates and ICD is not that.

The ICD is a machine, if you will, that responds to a regular life-threatening heart rhythms from the lower chambers of the heart with pacing that corrects a fast rhythm and promotes a normal heartbeat. So it sets out the shock or defibrillation that resets the heart rhythm to prevent sudden cardiac arrest or a big heart attack or the heart just really stopping. An ICD also records and stores information about your heart rhythm and therapies and delivers that by the ICD to your doctor for review.

It's an incredible thing. An ICD can also be programmed to work as a basic pacemaker as needed. Sometimes after a shock is delivered, the heart may beat too slowly.

The ICD has this backup pacemaker which can stimulate the heart to beat faster until the normal heart rate rhythm returns. The ICD can act as a pacemaker anytime the heart rate drops below what is set in the machine in the computer. Now you've seen those medicine shows where people get a shock to their hearts with paddles.

You know, they say charging clear and then they shock the heart. Very dramatic. And that way they can restart the heart.

An ICD is a small battery-operated box placed in the chest that monitors the heartbeat and when the heart goes too fast or has an irregular heartbeat, which is called an arrhythmia, it delivers a shock to the heart just like how they do it on the outside with the paddles only different. And this helps to get the heart to go back to its regular rate in rhythm. So the ICD is a heart therapy device that helps a person not die from their abnormal heart rhythm.

An ICD may also be recommended if someone has survived a cardiac arrest or if they have a history of coronary artery disease and have had a heart attack that has weakened the heart. If their heart muscle has become really stretched out and so the heart is enlarged or if there's a genetic heart condition that increases the risk of a dangerously fast heart rhythm. Now this is great technology, but the people who have them need to stay away from contact with batteries.

And this includes metal detectors, power generators, headphones, wireless chargers, and security systems. When the ICD detects an arrhythmia, it sends a shock to the heart and that could really be an unsettling experience. Before the shocks, some people may feel dizzy, they can feel their heart racing, feel that they might collapse.

The shock feels like a bump or kick in your chest or back. Most people who have received shocks from their ICDs describe them as startling, jolting, or unsettling, but really not painful. The pain, if there is any, usually lasts only a second and there shouldn't be any discomfort after the shock ends.

The jolt from the ICD brings the heart rhythm back to normal to control potentially life-threatening arrhythmias or rapid heart rates. Now the reason I'm bringing this up today is because if the person who has an ICD is diagnosed with a terminal illness and receiving hospital support, what happens with the ICD needs to be discussed. Now the person could be dying from their heart disease or they could have something totally different, but you know the heart disease is still there and the ICD is still inside of them.

Now many people wrongly believe that turning off the ICD means immediate death. This is not true. Remember that the ICD only fires when the heart rate is too fast or irregular.

It's a safety net that's available only when needed, otherwise it just sits there quietly minding its own business. But when it delivers the shock, and we're talking about for somebody who's in hospice, who's at the end of their life, so when they deliver, when it delivers a shock, the person can feel pain and discomfort. Turning off the shocking function is not a requirement for admission to hospice, but the goals of hospice are care to preserve quality of life during the dying process.

So it's really a good idea to turn it off and to make that decision ahead of time. Now this should not be an isolated decision, but instead made in the context of the larger goals of care. ICD should be considered in terms of the potential benefits and look at the burdens and the patient and their surrogates, family, whoever, have the right to accept or refuse its interventions just like any other treatment.

In order to make a truly informed choice about whether or not to turn off the shocking function on the ICD, I have five things I want you to think about. Number one, leaving the defibrillation function on can cause the patient to experience pain if the device delivers a shock near the end of life. And that might not be something that they want, and it might not be something that the family wants to see happen, and so it's worth considering what's the benefit of having that happen.

Turning off the shocking function means the device will not be able to provide all of the available methods of life-saving therapy in the event of a potentially fatal heart rhythm. Leaving the shocking function does not guarantee, however, that in the event of an abnormal rhythm, the heart will return to a normal pattern of breathing. Remember we're talking hospice, we're talking end-of-life, people with a less than six-month prognosis, you know, consider that the healthcare practitioners would not be surprised if they were to die within the next six months.

And so the question is, is it something that the person wants to continue to have going off in their body? The third thing to think about or to know is that turning off the ICD will not cause immediate death. Remember, it's only there if the heart goes too fast or has an abnormal rhythm. So for many people, they can have it in their body and have it never go off or have it go off once in their entire life.

So it's not going to cause immediate death. Number four, turning off the ICD will not be painful, nor will the patient's death be more painful if it's turned off. It's possible that their death might be more painful if it's going off, but it's not going to be painful to have it shut off.

Number five, decisions about deactivating a pacemaker are often made separately from the decision to turn off the defibrillator and depends on the reason for the pacemaker and the person's heart rhythm. Both are justifiable, however, on ethical grounds, depending on the patient's overall goals of life. Deactivating a pacemaker may result in changes in a patient's symptoms, or the ICD can be turned off and the pacemaker can be left on.

And typically that's what happens, is that people make the decision, I don't need to be shocked anymore, but the pacemaker can, you know, can help pace my heart to keep it going should that become necessary. But as the person dies, the pacemaker is not going to be able to overcome the dying process. If a plan for turning off the ICD has been made in advance, the manufacturer's representative will come to turn it off or reprogram the ICD.

If plans have not been made in advance, the backup plan is to have the hospice, the hospice nurse or place of residence, to have a magnet that'll turn off the ICD if the patient is being repeatedly shocked and wants the ICD turned off. So it's interesting is that the way these are managed, like I said, is with magnets, which is why you can't put your magnets while you're up and walking around. And the magnet has to be like right on the person's chest in order to shut off the ICD.

So in an emergency situation, if plans have not been made in advance and you say, okay, I want this thing off, what the hospice nurse will do is that they'll tape a magnet over the heart. And this stops the ICD from sensing and delivering shocks. If that magnet is removed, the ICD will begin sensing again and can then begin to deliver shocks.

So what the nurse will do is just bring a magnet in, they'll tape it right over the chest, and that just deactivates the ICD. But if somebody comes in and says, what's this magnet doing on dad's chest and rips it off, the ICD will start again. For most people, having their ICD switched off is a big decision.

But if you change your mind, it can be turned on again, reactivated at any time. So this is one of those decisions that if you have an ICD or you have somebody in your family with an ICD who is in terminal or end state disease, particularly if they're in hospice, this is a conversation to have so that they don't experience any unwanted pain or any unwanted interventions at the end of life. Charlie, do you have any questions about that? Yeah.

I would just imagine that there would be something, because what you were saying a lot was sometimes it's not clear whether to keep the ICD running, to shut it off. I mean, people don't have these discussions in advance. They're just left to circumstance and deal with it when an emergency pops up.

Well, if people have these kinds of conversations, we would not be necessary. And I would love just to go on the record to not be necessary. I would love for people to have these conversations.

But the reality is that nobody wants to talk about, well, I won't say nobody because you and I do, but most people don't want to talk about the end of life. Most people don't want to talk about, well, what about resuscitation? What about this machine that I have in my chest? People can have them in for 10 years and never once have put it in their advance directive or if they have an advance directive or talked with their durable power of attorney, if they have a durable power attorney, what to do with this machine? And we're here to raise awareness and let you know there in the past, like 10 years ago or so, the ICDs were a bit different and they would continue to go off after a person died. And that was a real nightmare for families and for hospice nurses, because they'll just, in the past, just continue to fire these shocks.

And so, you would have somebody who's died, but they're still getting these shocks and jerking. And it was really traumatic. Pete Wow.

Wow. Okay. Changed how they work.

So, that's not a case anymore. I mean, if you go and do like a literature review, you'll look about 10 years ago, you'll see all kinds of articles about ICDs and death and them going off and not being something anybody wants to experience. But now they're programmed differently.

They're only going to go off if there's a rapid heartbeat or an arrhythmia. Okay. And the other thing too, oh, I'm sorry.

But in that dying process, you can have an arrhythmia, which will then shock you if you don't have that machine turned off. Right. I'm sorry, what were you going to say? When you had said, I mean, you know, people have to be careful going through different machines, including security.

I mean, if you fly, there's airport security. Is it just airport security systems will not, you know, screw up an ICD? Or how do people get through airport security? Well, when you have an ICD implanted, they'll give you a card that says, I have this ICD. And so then you'll go through special screening processes.

And I think they hand-wand you and they can't keep that, they can't put it close. And they, you know, so there's a certain distance away and they do it relatively quickly over that area. So they can still, you know, pat you down and scan all the other parts of you, but they can't be too long.

But you get that card. So, you know, and we also in our resources have a really good guide on sort of like everything you've always wanted to know about the ICD and didn't know to ask it. It's really, really good.

So check that out in our, in our resources, it gives all the details. I didn't go into all the details of like living with an ICD. Um, my focus in this case was on the end of life with an ICD and not making more trauma for yourself and for your family.

So in the off chance that what has an ICD and decides to go to a club and that club has like, you know, a security screen and all that sort of stuff, but you just whip out your ICD card. I mean, cause different, I'm getting too extreme when I say nightclub, but you know, um, could that be an issue? It could be. That's why you have the card.

And that's why, you know, you go, when you get your ICD, you're typically even nurse goes through a lot of teaching with you. There's ICD support groups. I mean, there's like, like with any kind of technology that you're given the opportunity to learn as much as you can about it so that you don't get yourself into a difficult situation.

But even if, um, you know, how you leaned up against a magnet or a magnet, it would. Why, why wouldn't you do that? I don't know. But if you were so inclined, um, you know, you're dating a robot.

I don't know. Um, it's just important for safety tip folks. It's just, if you're in close contact with it, as soon as you remove yourself from it, um, yeah, you're getting kind of in the, in the weeds here, Charles, but yeah, I guess, but yeah.

Okay. All right. Thank you.

Third Half

You're welcome. In our third half, uh, I have a poem for you written by Malcolm Farley and published in the American Journal of Nursing. This confusion, two wrinkled hands appeared floating among the window dressings of a banana Republic on eighth Avenue.

And I thought for an instant, they were my mother's drained of blood, pale as ghouls gripping a shopping bag. Like the one I held when I looked up to challenge her, bracing myself against her rage. What I saw was my own baffled face instead in the tricky ether between me and a mannequin on the far side of the store's plate glass.

But her maternal grasp hovered there too, attached to my own arms, clutching the bag with gloves I'd bought to claim it. And then she seemed to manifest in full shatterproof and dour wool pants, white blouse and lilac scarf. When I glanced down at my actual heads to confirm they were still mine, what I found was hers in real life, sutured to my wrists, the same thick fingers and stubborn thumbs, her lifeline streaking like lightning bolts across the hollows of my palms.

In a searing zigzag flash, I see her fists, her scrunched up eyes and hear a shriek. She pounds my head against the wall so hard it leaves a dent. Thunder echoes in my ears, but no, a grim pig boy delivery van is rambling uptown to Hell's Kitchen.

It was that nurse in hospice. She ignited this confusion last July, by accident, as I bowed my head right next to hers. To ease another dose of morphine down, she stared at me and said, Oh, honey, you look just like your mom.

And thus goes another episode. Please stay tuned to listen to the continuing saga of Everyone Dies. This is Charlie Navarette, and from the TV show Saturday Night Live, it was reported that 92-year-old Rupert Murdoch is set to marry his 67-year-old girlfriend.

The couple is registered at Campbell's Funeral Home. You know, I'm turning 67 in a few weeks, and I didn't think of myself as the young whippersnapper, but I guess compared to Rupert, we're pretty young, huh? What is it, wife number four or five? Rupert, call me. And I'm Marian Matzo, and we'll see you next week.

Remember, every day is a gift. for professional medical advice or treatment. Always seek the advice of your primary care practitioner or other qualified health providers with any questions that you may have regarding your health.

Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have heard from this podcast. If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor or 911 immediately. Everyone Dies does not recommend or endorse any specific tests, practitioners, products, procedures, opinions, or other information that may be mentioned in this podcast.

Reliance on any information provided in this podcast by persons appearing on this podcast at the invitation of Everyone Dies or by other members is solely at your own risk.

.jpg)